“When Things Go Wrong, Where Was The Board?”

“The best measure of adaptation to unanticipated risks in the biological setting is the length of time a species has survived.” — Richard Bookstaber

When things go wrong, one of the first questions is, “Where was the board?” One of the first answers often is, “They weren’t asking the right questions.”

Shifts Happen Fast! Click here to catch up on the first and second parts of this blog series.

When Albert Einstein was a professor at Princeton, he was told he needed to change the questions he asked on the final exam. Apparently, students had discovered that Einstein kept asking the same questions, so they passed them around. He refused to change them. When asked, “Why?” he replied, “Because the answers keep changing.”

Lesson Worth Learning:

Failure to adapt is a failure of governance.

- Where was the board?

- What questions should they have asked?

- What could they have done?

What critical questions should boards always ask of themselves and others?

- What’s essential?

- What are the most important things a board can do to enable rapid adaptation?

- How can a board make the highest and best use of organizational resources, including everyone’s time?

Using longevity as the measure, corporate lifespans on the S&P 500 have plummeted as the momentum of change has accelerated, as has the volatility of both growth and decline. The average lifespan of an S&P company has dropped from 61 years in 1957 to just about 18 years today – a decline of more than 70% in almost as many years.

Some are forecasting it will be as low as 12 years by the end of this decade. As of 2021, on average, an S&P company was being replaced every two weeks. It is estimated that 75 percent of the 2019 S&P 500 firms will be replaced by 2027. U.S. companies are not alone. Of the 100 companies in the FTSE 100 in 1984, only 24 were still listed in 2012.

The composition of the S&P 500 index changes over time due to various factors such as mergers, bankruptcies, and changes in market capitalization. While acquisitions or mergers may have been the plan for some, for others, entire industries have been displaced, not just companies.

The landscape constantly shifts – quickly. Disruptive events can emerge at any time. Businesses (large or small) may fail if they cannot keep up with or respond effectively to new entrants, industry shifts, or market demands. Established companies that become too complacent or are too finely adapted to specific circumstances are especially vulnerable to disruptive forces. Existential opportunities may be missed and become existential threats.

Big businesses often have more resources to weather some of these challenges, but they still succumb if issues are not addressed promptly and effectively. Staying agile, adaptable, and forward-thinking is crucial for the long-term success of any business, regardless of its size.

Many of the companies removed from the S&P 500 were, “household names”. Presumably, there were a lot of smart people on these boards. Where did they go wrong? What questions should they have been asking?

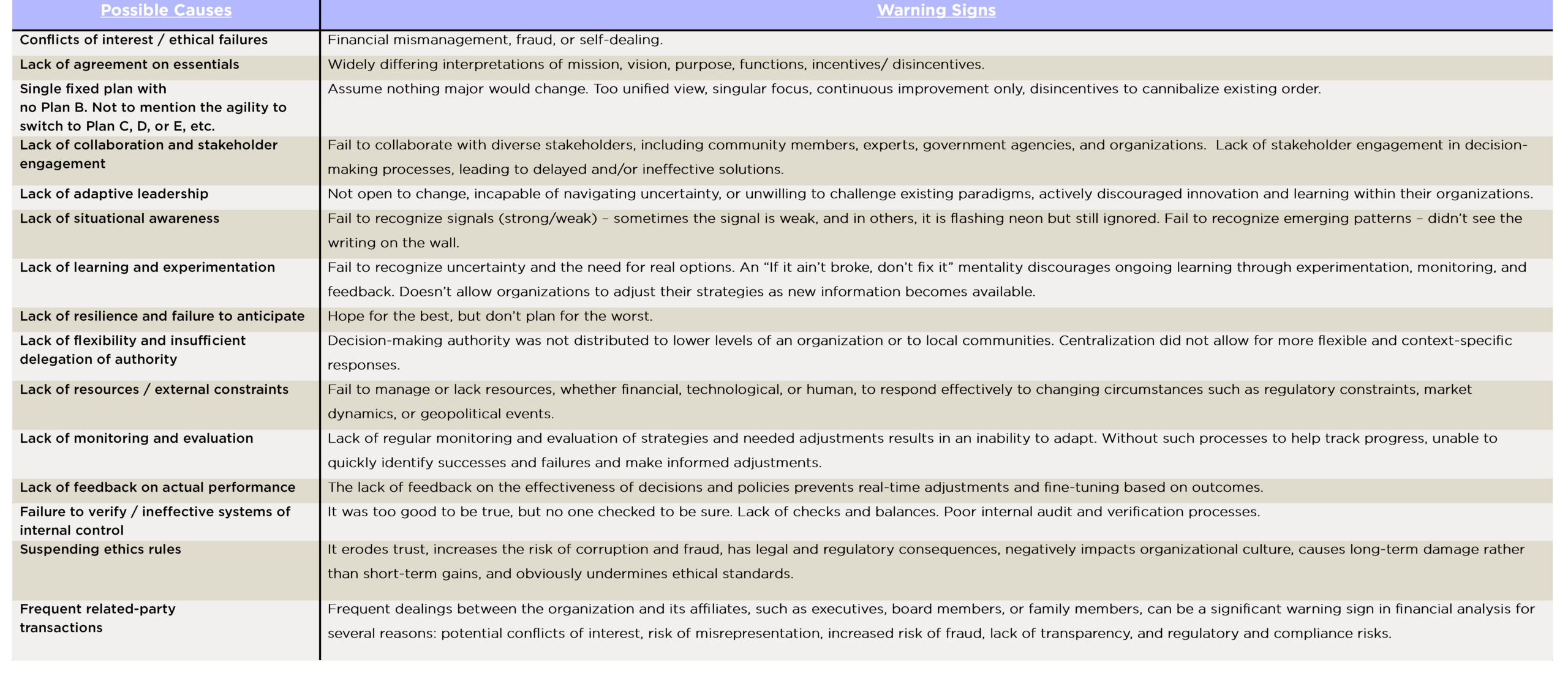

No company or industry is immune, no matter how established or venerated. The following figure describes some of the possible causes of these failures. These causes are not mutually exclusive, and they interact. Have a look at this list and see how many of these warning signs are evident in your organization.

This blog was adapted from Rick Funston and Jon Lukomnik’s Adapt or Fail: A 5×5 Governance Framework for Boards of Directors (De Gruyter Brill, 2025).

Catch up on the first and second parts of this blog series.

Out now in eBook and paperback

[Title Image by Dragon Images/Getty Images; Opening quote from Richard Bookstaber, “A Demon of Our Own Design: Markets, Hedge Funds and the Perils of Financial Innovation.” Wiley & Sons. 2007, p. 232]