Resistance and Immigration: Modern Lessons From a Nineteenth-Century German Revolutionary

From insurgency in Europe to Abolitionism in the United States, Friedrich Hecker's transatlantic odyssey illuminates broader patterns of cultural exchange, social reform, and political integration that have defined the American historical experience.

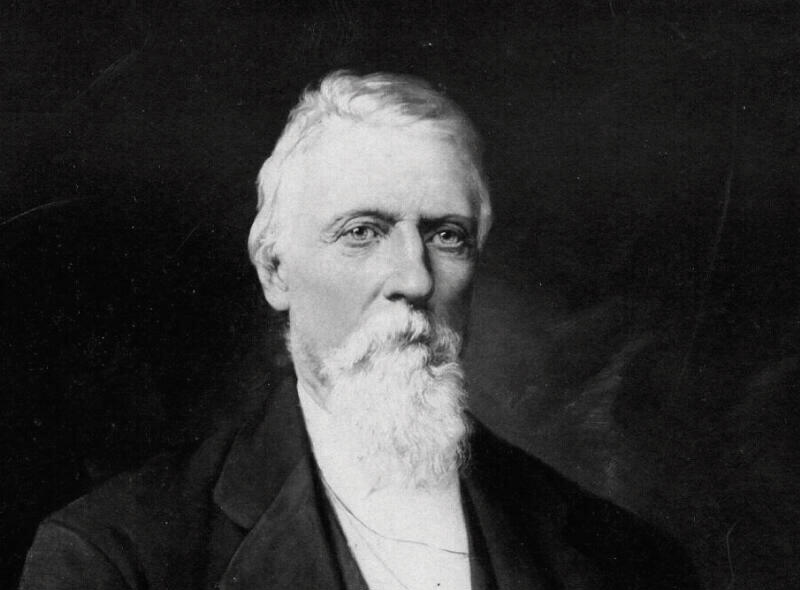

By the time Friedrich Hecker (1811–1881) was thirty years old, he had committed himself to a life of constant political resistance. The early 1840s saw the young Hecker become an elected member of the lower chamber of parliament in the nation of Baden in Southwestern Germany. He challenged aristocratic rule at every turn and with ever-increasing fervor. He fought against press censorship, against limits on the freedom of assembly, against measures to restrict the organizing of civic militias, and especially against the lavish and decadent spending on the royal court and its pet projects.

The charismatic Hecker quickly became a folk hero throughout the 34 nations that comprised the German Federation – being referred to as “the people’s Hecker.” Frustrated after five years of attempting to forge an effective opposition from within the government, Hecker began to organize huge public demonstrations – especially after revolutions broke out simultaneously across Europe in February and March of 1848. His impatience for fundamental political reform peaked in April of that year, when German moderates and conservatives refused to completely sweep away aristocratic rule.

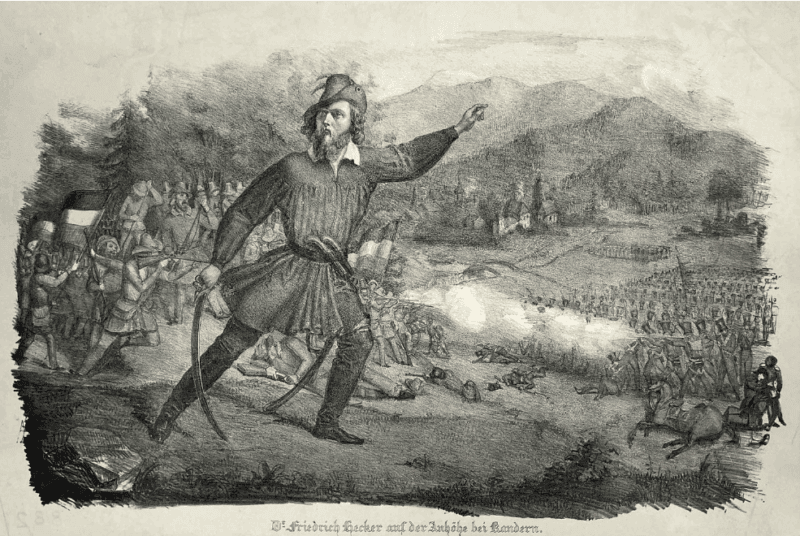

Only then did Hecker wager his entire life against overwhelming authoritarian power and start an armed rebellion. His chances of success were all but nonexistent – yet he continued to resist. His insurrection lasted only ten days and was defeated in the foothills northeast of Basel, Switzerland. “With sword unbroken, but with a broken heart.” (Heinrich Heine, Enfant Perdu, 1851)

A Transatlantic Tapestry

After the failure of his ill-fated rebellion, Friedrich Hecker and his family briefly fled to Switzerland and then immigrated to the United States in October of 1848. Upon his arrival in New York, he was greeted with messianic passion by 15,000 German Americans.

Hecker had always idealized the American Republic – a people who could govern themselves without the need for paternalistic absolute authority. He found his redemption in the American Midwest, quickly becoming involved in the abolitionist movement, equating southern slave holders with the same aristocrats he had fought in Europe. In 1856, he helped organize the fledgling Republican Party and was an elector from Illinois for the party’s first presidential candidate, John Fremont. By 1860, Hecker helped purge the party of its anti-immigrant elements and organized German Americans for Abraham Lincoln.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, he enlisted immediately and organized a regiment made up exclusively of diverse immigrants – which included Germans, Swiss, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Hungarians, and even an all-Jewish unit. This regiment and dozens like it throughout the North fought with bravery and with distinction to keep their adopted country unified and to defeat the scourge of slavery. Like every wave of immigrants that followed them, the refugees of Germany’s Revolution of 1848–49 enriched the American tapestry. When has immigration ever been bad for America?

Limitless Possibilities

But the story of German immigration is much larger than the 5,000 political refugees known collectively as the “48ers.” Today, more than 41 million Americans identify Germany as the country of their family’s origin – the largest of all immigrant groups, with Americans of Mexican descent close behind.

While there was a sizeable German population in the United States before the mid-nineteenth century, massive German immigration really started around 1840. Between 1840 and 1860, 1.5 million Germans immigrated to America, which is especially astounding considering the total population of the US was just 24 million. The reasons to emigrate were much the same as they are today: political persecution; the desire for freedom; and the very real belief that America was indeed the land of “limitless possibilities” (unbegrenzte Möglichkeiten).

However, again like today, most were fleeing poverty and environmental disaster – the same potato blight that forced so many Irish immigrants to America affected the German states as well, where the damp and cold weather also caused the failure of the grain harvests. To avoid starvation and debt, farmers either sold their land or simply abandoned their property. They then smuggled their families to the port cities of Bremen and Hamburg to sail to America, as it was illegal in most of the 34 German nations to emigrate without explicit legal permission.

Overwhelmingly, these immigrants ended up in the American Midwest in what became known as the “German Triangle:” outlined by Cincinnati in the east, St. Louis in the west, and Milwaukee in the north – my own family immigrated first to Ohio and eventually settled in Chicago. All these cities were hubs of German cultural activity, where there were often multiple competing German-language newspapers, theater companies, opera houses, and sports clubs. With the advent of the Civil War, German Americans constituted the single largest contingent of foreign-born soldiers. (This willingness to make the ultimate sacrifice for their country has been repeated by a diversity of immigrants in every US military conflict to the present day.)

German America Today

After the Civil War, German immigration continued at a brisk pace, hardly impacted during the 1880s by the first restrictions in US history to limit foreigners. And even with the national quota system of the 1920s, Germans were ‘attractive’ immigrants within the racist system of the time – they were white, generally well educated, and had a reputation for being industrious. (In the jargon of today, Germans were not “from shit-hole countries.”)

“This willingness to make the ultimate sacrifice for their country has been repeated by a diversity of immigrants in every US military conflict to the present day.”

But two world wars in the twentieth century took an immense toll on German culture in America, especially after the Second World War and the Holocaust. German Americans stopped speaking the language with their children, and the vast and vibrant German-language culture of the nineteenth century was reduced to enclaves of German American clubs and the clichés of Oktoberfest.

The loss of German American identity certainly also speaks to the ‘success’ of the ethic group to assimilate into the greater cultural fabric of the United States. Today, Americans who identify as having German heritage seldom identify as “German American.” Assimilation always is a double-edged sword – while it provides immigrant populations with a new and homogeneous national identity, it tends to destroy cultural diversity.

Learn more in this related title from De Gruyter Brill

[Title Image: Colored lithograph depicting the battle near Kandern, 1848, where the Hecker uprising attempted to overthrow the Baden Monarchy. Courtesy of the Wehrgeschichtliches Museum, Rastatt. CC BY-NC-SA]