Healing Holocaust Survivors: An Interview with Stella Maria Frei

Eighty years after the Nazi surrender, a new open access book urges us to reflect on conflict’s enduring traumas and the complex role humanitarian organizations play in reshaping displaced lives.

In Healing Holocaust Survivors: Politics of Psychological Rehabilitation in Postwar Europe, historian Stella Maria Frei explores how humanitarian organizations like the UNRRA and the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee responded to the mental health needs of Holocaust survivors and other refugees in Displaced Persons Camps between 1944 and 1948. Her research uncovers a lesser-known strand of the postwar experience in Europe and beyond – where psychological care was not just about healing individuals, but also about shaping future citizens in line with the political visions of reconstruction.

In this interview, Frei discusses the emotional landscapes of the camps, the political dimensions of psychological aid, and why these early efforts at rehabilitation still echo in today’s global responses to forced migration and trauma.

Billy Sawyers: Can you tell us a bit about your academic and intellectual background? How did you first become interested in this field?

Stella Maria Frei: I grew up in a family where history was very present – through stories told by my grandparents. It felt like I grew up alongside history. I remember learning about personal experiences and historical facts surrounding WWII and National Socialism, probably far too early for a child. But I was insatiably curious and didn’t take no for an answer.

Fast forward to high school, when I came across the work of Israeli-American sociologist Aaron Antonovsky. While working with Jewish survivors in 1950s Israel, he posed a question that struck me deeply: How is it that some survivors endured Nazi persecution and went on to thrive, while others remained what he called “living skeletons”?

That question stayed with me. I had always been drawn to fundamental questions: Why are things the way they are today? What makes a good life? What do we truly need, deep down, as human beings? I’ve long been fascinated by the inner workings of the mind – but always with a political and historical twist.

That intersection – of history, politics and psychology – became the throughline of my academic work. I studied History, Eastern European Studies, American Studies, and Creative Writing in Hamburg, Germany and at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. It was at Smith that I was introduced to the postwar world and the history of Displaced Persons – a moment that brought many of these threads together.

My research today sits at the crossroads of history, politics and psychology. It’s driven by a deep curiosity about how people live on after catastrophe, and how, in true Foucauldian fashion, psychology and psychiatry were instrumentalized to exert power on individuals.

BS: Healing Holocaust Survivors focuses on the experiences of Nazi victims in refugee camps such as those set up by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). How did their new status as Displaced Persons (DPs) shape “life after death” for the survivors of concentration camps?

SMF: Recovering from Nazi persecution meant that physical liberation needed to be followed by psychological liberation. Naturally, this was a lifelong journey, if it happened at all. For many DPs this started in the messy, spontaneously assembled, deeply transitory space of the DP camps.

It’s important to remember that the group of DPs was anything but homogenous – people from all walks of life, Jewish and gentile alike, with varying wartime experiences and from many different countries, found themselves thrown together in these camps. Life after death in a DP camp meant being suspended in a prolonged waiting room, and with it, a prolonged uncertainty about what the future might hold.

“The fate of the survivors became a bargaining chip in the larger game of postwar geopolitics.”

For many, the DP camps became a space of reckoning where the DPs found out who they had lost – and who, miraculously, had survived. The camps provided food and medical care, including some physical rehabilitation. But they also gave people the first opportunity to begin grappling with the full emotional and psychological aftermath of what they had endured. To begin asking the question: How do I go on living?

From what I’ve gleaned from the sources, the camps were a kind of kaleidoscope – made up of complicated relief at having survived, the heavy weight of grief and loss, and a relentless drive to build a better future. They were deeply complicated places. In the early stages of the DP operations, former enemies were often housed side by side – for example, Polish Jews and gentile Ukrainians – and the conditions were far from ideal: overcrowded, lacking in privacy and emotionally fraught. One question echoed through the barracks: Where can we go? Gaining clarity about the next destination significantly affected the mental state of the survivors, as many social workers working with them reported.

BS: How has public commemorative culture tended to obscure or highlight the psychological struggles of survivors in the immediate aftermath of World War II?

SMF: At the outset, I was struck by a curious gap in research with regards to the immediate postwar years. Extensive research has been conducted about the war itself, but its aftermath has been neglected, both in research and in the wider public perception. For a long time, public commemoration focused on survival and liberation, but the immediate postwar needs and personal struggles of the survivors have been historically underrepresented. In fact, the fate of the survivors became a bargaining chip in the larger game of postwar geopolitics – a dimension that has long been neglected in public memory.

BS: How did contemporary ideas about nation-building and citizenship influence the psychological interventions offered to survivors?

SMF: Psychological rehabilitation in the postwar period was not neutral – it was shaped by the political agendas of the time, particularly ideas about nation-building and the kind of citizens needed to (re)build societies. Survivors were not just seen as individuals in need of healing, but also as potential future citizens who had to be ‘rehabilitated’ into specific political frameworks.

“The psy-disciplines became tools not just for healing, but for shaping the emotional and political selves of survivors in line with broader geopolitical goals.”

In DP camps, psychological support often operated under implicit and explicit expectations of adaptability. The goal of psychological rehabilitation was to create ‘healthy’ survivors – those who could adjust to life in a liberal democracy (this was the focus of UNRRA) or, in Zionist contexts, contribute to the building of the modern state of Israel. Models of Western, mostly Christian individuals, rooted in heteronormative family systems and willing to become productive citizens, shaped what was considered psychologically desirable for UNRRA. For the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), psychological rehabilitation was often tied to adaptability and alignment with Zionist ideals – survivors were encouraged to become emotionally stable, future-oriented individuals who could contribute to the building of a modern Jewish state. This created tensions, especially for those who could not or did not want to conform to these narrow definitions.

Organizations like UNRRA and the JDC, while offering real care and support, also functioned within systems that sought to produce stable, governable subjects. The psy-disciplines became tools not just for healing, but for shaping the emotional and political selves of survivors in line with broader geopolitical goals. In that sense, psychological interventions were deeply entangled with the reconstruction of the postwar order – and with the ideologies that underpinned it.

BS: May 8, 2025, marks 80 years since the end of the Second World War. How does your research on postwar psychological rehabilitation reshape our understanding of the postwar period?

SMF: My research shows that psychological rehabilitation after WWII was never just about individual healing – it was a deeply political project, tied to the broader project of shaping the postwar world. For the first time in large-scale transnational humanitarian efforts like UNRRA or the JDC, psychological needs were taken seriously. But they were also instrumentalized. Survivors’ mental health became entangled with postwar geopolitics, migration regimes, and ideas of who would make a ‘good’ citizen in a future world order.

“The UN emerged from moral and physical devastation with a powerful vision: that only by working together – across borders, ideologies, and religious divides – can we prevent war and foster wellbeing for all.”

My work challenges the idea of 1945 as a neat moment of liberation, and instead reframes the immediate postwar period as a messy, emotional and politically decisive aftermath in which the moral consequences of the war were actively negotiated against the backdrop of postwar geopolitics. My book also traces the roots of multilateralism, particularly the founding vision of the United Nations, which sought to establish peaceful cohabitation among nations. Programs and incentives run by organizations like UNRRA and JDC – even the psychosocial ones – were aimed at creating order in a chaotic postwar landscape, to prevent another war, and to lay the groundwork for democracy and peace.

I believe this is a crucial message to reflect on in 2025 – a year that marks not only 80 years since the end of the Second World War, but also the 80th anniversary of the founding of the United Nations. At a time when multilateralism is under intense pressure, with growing voices questioning its legitimacy and impact, the postwar years offer an important reminder of why these institutions were created in the first place. The UN emerged from moral and physical devastation with a powerful vision: that only by working together – across borders, ideologies, and religious divides – can we prevent war and foster wellbeing for all. Reflecting on this history can help us reconnect with the core virtues of the UN and rethink how to meaningfully adapt them to today’s challenges.

BS: Who or what do you see as the biggest influences on your scholarly work?

SMF: Working at the intersection of history, political science, psychology and sociology, I feel like I am treading a pretty new path. In terms of closeness to topic and style of storytelling, I drew a lot of inspiration from Tara Zahra, Dagmar Herzog, and Atina Grossmann. I want my work to be academically sound and an original piece of research – but also to be readable and moving, all of which I believe these authors achieved.

BS: What kind of impact do you hope your book will have on readers, both within academia and beyond?

SMF: I would be happy if my work could contribute to a continued opening of minds within the historical community – that it is safe and worthwhile to transcend the boundaries of our discipline in the pursuit of knowledge. I also hope my book helps to show that we must stop understanding history as something that some important (mostly white) men did in the past. History is still with us, in us, today, and it is ultimately the sum of our individual experiences.

Transcending my own work – let’s stay humble here – I believe we need to shift the old question of whether we ‘learn from history’ toward something more urgent: a question of responsibility. How and where does history ask us to go, to heed its call for responsibility to prevent further war, violence, and suffering? How can we take the painful parts of our history and transform them into positive action for a more just, equal and peaceful world for all? I quote Julius Lester in the epigraph of my book: “History is not just facts and events. History is also a pain in the heart and we repeat history until we are able to make another’s pain in the heart our own.”

“That, to me, is the deeper promise of doing history: not only to document the past, but to let it move us.”

BS: Were there any particularly striking or unexpected findings?

SMF: As probably every author has said at some point, I believe my book offers several important strands to consider: the use of psychosocial expertise in a humanitarian setting, postwar geopolitics, and the relationship between the psy-sciences and power. What stuck with me personally was the human dimension of it all. It wasn’t necessarily new to me, but I was repeatedly moved by the resilience the DPs displayed, and by the deep willingness of so many – especially the social workers in the camps – to put their own lives in the service of others.

And returning to my initial questions of living life after death: Archival sources and the interviews I conducted with survivors confirmed that, besides physical safety, the core salve to displacement was new forms of belonging, affiliation and love – a new form of identity that promised community, home and connection. And lastly, as psychologists Edith Eva Eger and Viktor Frankl – both Holocaust survivors who made it their life’s work to draw the lessons of their survival into psychotherapy — put it: Everything else can be stripped away, but the freedom in your mind, the freedom to choose what to think and what to believe, cannot be taken from you. The ultimate savior is inside our own minds.

BS: Can you describe the concept of “radical hope” in the context of your research?

SMF: After the perceived failure of humanity in the rubble of WWII, the international community came together to pursue what I would call a project of radical hope, driven by a strong moral imagination. The founding of the United Nations marked a moment where cooperation – not competition – was envisioned as the guiding principle of a new global architecture for peace and security.

This early form of multilateralism was rooted in the belief that only by working together – across borders, belief systems, and political divides – could another global catastrophe be prevented. Emerging from the catastrophe of two world wars, this was an ambitious and radically hopeful vision for the future.

In a time where great power competition is once again on the rise, we should remember this moment of radical hope – and ask how we can reclaim it today when faced with a new surge of geopolitical unrest and a conversation about international security that sometimes feels as if war is simply inevitable.

On an individual level, it was paramount for the survivors to find their own reason for hope, and they mostly found it in community. Deciding to live on after traumatic experience is, I believe, in itself a radical act of hope.

Coming soon in hardcover and open access eBook

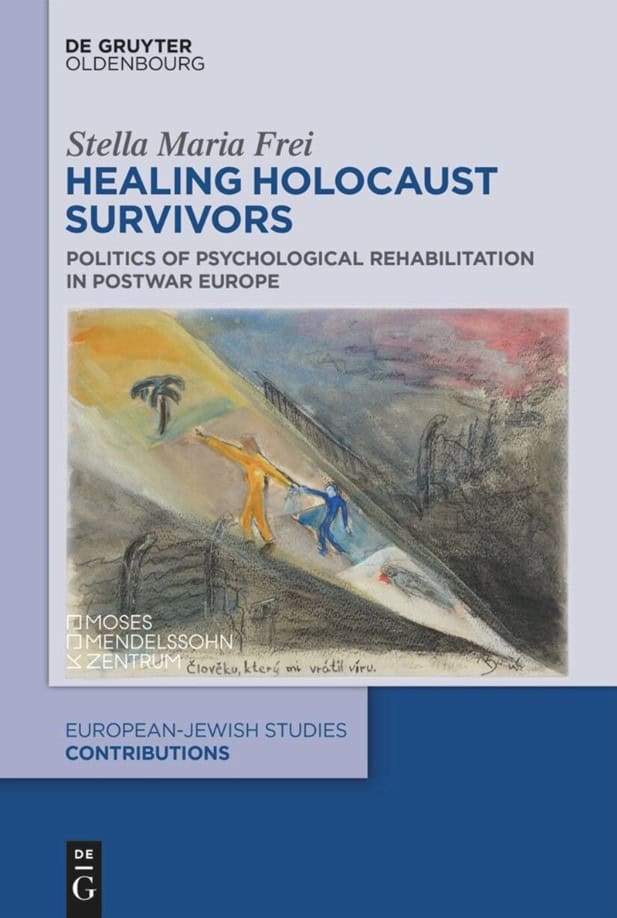

[Title Image: Survivors of the Nordhausen concentration camp receive medical care in an UNRRA rehabilitation center. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park. Public Domain.]