The Home Front: Hardly a Refuge from War

What happens on the home front during times of war? Is the home really a refuge, a space that is sheltered from the violence of a war taking place “elsewhere,” as so often is thought? Or does it entail its own set of daily challenges linked to the conflict at hand? We see the plight of the Rohingya, Yazidi and Syrians, among others, frequently in the news. But how did women experience the home front in the past?

A hundred years have passed since the signing of the Peace Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919, which brought a formal end to the First World War (1914-1918). Yet, the effects of this war were far from over. They continue to capture the international imagination, with such recent accounts as Peter Jackson’s 2018 documentary film, They Shall Not Grow Old, and Kate Moore’s 2017 bestselling book, The Radium Girls. The 100th anniversary of World War I and the preceding years of German colonial conflicts inspire us to revisit tales that emerged out of these violent developments.

“We must look outside of the traditional canon of war literature where stories of war are often stories of men’s adventures, men’s comradeship and men’s suffering.”

In order to understand the experience of war in early twentieth-century Europe and its colonies beyond the arenas of actual combat, we must look outside of the traditional canon of war literature where stories of war are often stories of men’s adventures, men’s comradeship and men’s suffering. Consequently, the stories about what happens on the peripheries of combat zones, in homes and to members of traditionally underrepresented groups have long remained invisible, disregarded and/or forgotten. In the context of Germany, one glaring omission has been the war stories of women.

A number of narratives by women only recently have been excavated from archives to provide new insights and open up questions about the gendered experience of war. These accounts often highlight the home front, where women waited, mourned, protested, fought for their own and their children’s survival, and were encouraged to adopt the patriotic fervor, Kriegsbegeisterung (war enthusiasm), of and for their countries. In fact, their stories have broadened the very definition of war beyond the conventional battlefields as they defy the notion of home as a safe space impermeable to historical events. They show us how important it is to dispel the perception of the home front as a refuge that both the political and cultural imagination has traditionally cultivated. Such a misconception only supports the bifurcated concept of distinctly gendered roles of men as combatants and active participants in the public sphere and women as noncombatant nurturers and emotional anchors in the private realm.

Yet, the truth is, women’s roles in the wars of the early twentieth century were extremely varied and even contradictory– not least as writers recording their war experiences. Thus, the story of the colonial wars and World War I cannot be told without understanding the profound intersections of gender, race, class and nation.

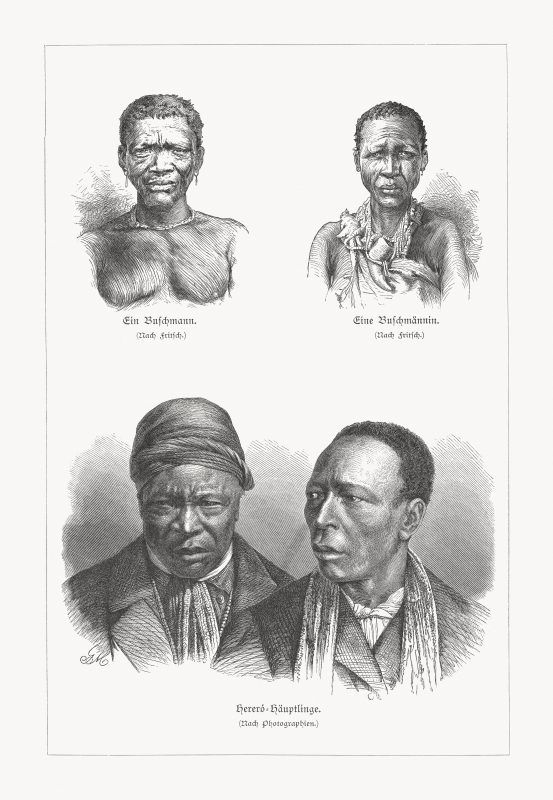

In the many German-initiated colonial conflicts in the early 1900s the dividing line between the front and the home front blurred for both the colonizing Germans and the colonized local populations. The theaters of war included the villages of indigenous people that were burned to the ground and the German colonial settlements that were attacked in German East Africa (today’s Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi). In German Southwest Africa (today’s Namibia), German troops forced native Herero men, women and children to leave their homeland entirely and march into the Omaheke Desert, or to live under inhumane conditions in makeshift concentrations camps.

“Women fought on many fronts, they were caretakers, victims and/or perpetrators, they rallied for one cause or another, endorsing or opposing collective violence, they shared the burdens of loss and enjoyed agency and authority.”

The song of a female Herero survivor captures the devastating experience of fleeing and losing everything: “People are distraught; the child has lost its mother, the mother has lost her husband, the lambs have gone to suckle the goats” – an anomaly in nature that serves here as an image of a world turned upside down. There was no place that provided refuge during the colonial wars against the Herero and Nama in German Southwest Africa (1904-1907) and the Maji Maji War in German East Africa (1905-1907). The song documents the atrocities committed against tens of thousands of Herero in a war that is known today as the first genocide of the twentieth century. And so have the stories of past refugees given that the United Nations count approximately 65 million displaced people around the world today.

These examples of oral histories of the Herero experience challenge the story of German colonialism that has been delivered mostly by German men who sought to “pioneer,” conquer and appropriate territories to advance personal and national interests. To complement and complicate the understanding of German colonialism are also the stories of German female authors like Helene von Falkenhausen, Else Sonnenberg and Margarete von Eckenbrecher, colonial settlers in Southwest Africa who also experienced the German-Herero Colonial War first .

These women published autobiographical reports about their traumatic war experiences, which included losing their husbands, small children, and/or property. Yet they also contributed to the one-sided perception of this war in the German motherland by spreading racist convictions, implied, for example, in Eckenbrecher’s assertion, “in cold blood, I would have shot first my child and then myself rather than fall into the hands of these [native] monsters.” On the contrary, in proven historical reality, the Herero were careful to keep enemy women and children safe. Additionally, statements like Falkenhausen’s contention that “there lies a particular appeal in forcing a previously wild country into a state of culture” sought to justify the violence against the native population and lay bare a racist undercurrent that perversely supports notions of German superiority – a patriotic discourse that threads all the way through WWI. In contrast, female missionary Hedwig Irle in Wie ich die Herero lieben lernte (1909, How I learned to love the Herero) strove for a vision of a multiracial Christian mission family as an idealized community, an antidote to violence, and a model for a pre-World War I concept of peace based in religious beliefs.

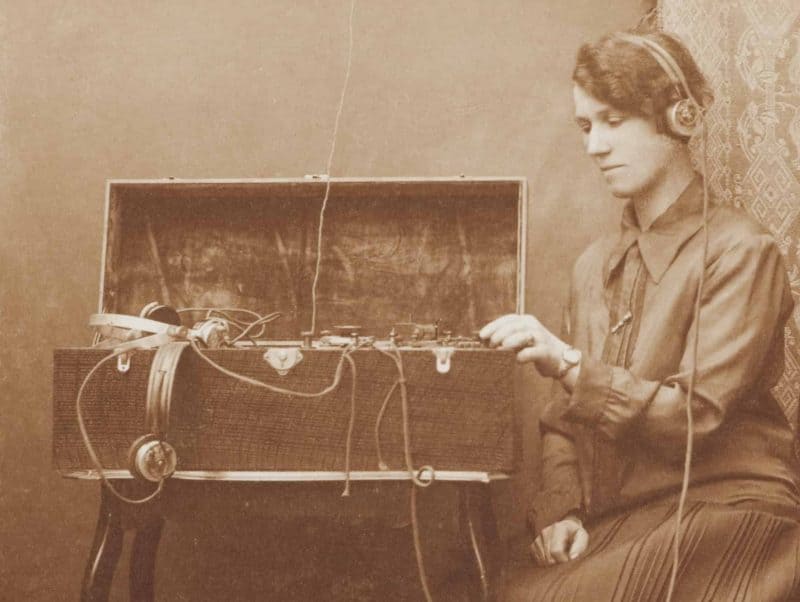

So, how did the story of women’s war experience continue in World War I?

To find out the answer, read the second part here.

[Title Image by H. Armstrong Roberts on Getty Images ]