The Home Front: Hardly a Refuge from War

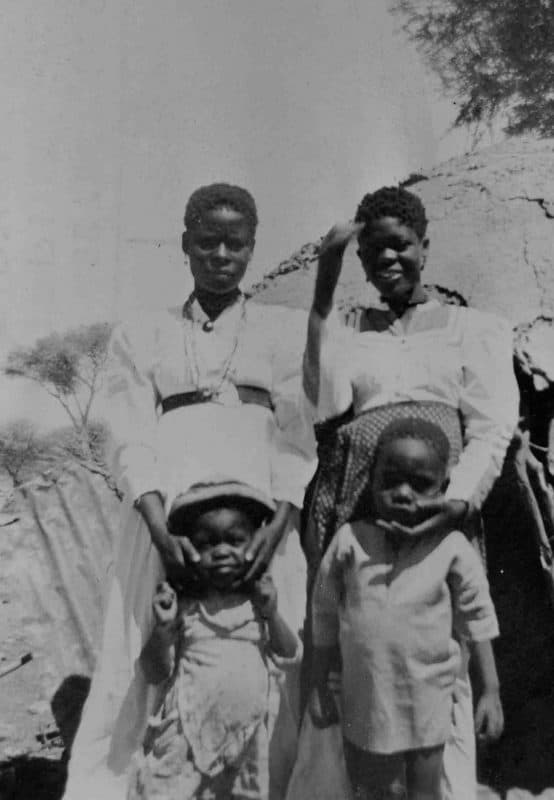

To complement and complicate the understanding of German colonialism are also the stories of German female authors like Helene von Falkenhausen, Else Sonnenberg and Margarete von Eckenbrecher, colonial settlers in Southwest Africa who also experienced the German-Herero Colonial War first hand. How did they portray women's stories and experiences in the home front back then?

These women published autobiographical reports about their traumatic war experiences, which included losing their husbands, small children, and/or property. Yet they also spread racist convictions, implied, for example, in Eckenbrecher’s assertion, “in cold blood, I would have shot first my child and then myself rather than fall into the hands of these [native] monsters.” On the contrary, in proven historical reality, the Herero were careful to keep enemy women and children safe. Additionally, statements like Falkenhausen’s contention that “there lies a particular appeal in forcing a previously wild country into a state of culture” sought to justify the violence against the native population and lay bare a racist undercurrent that perversely supports notions of German superiority – a patriotic discourse that threads all the way through WWI. In contrast, female missionary Hedwig Irle in Wie ich die Herero lieben lernte (1909, How I learned to love the Herero) strove for a vision of a multiracial Christian mission family as an idealized community, an antidote to violence, and a model for a pre-World War I concept of peace based in religious beliefs.

In both Germany and its colonies, the beginning of World War I was greeted with great optimism, and writers like Ricarda Huch, a seven-time-nominee for the Nobel Prize in literature, defended the war. But there were others who feared the consequences of the war and spoke out against the blind and reckless patriotism they saw around them. They walked in the footsteps of women like the Austrian pacifist Bertha von Suttner, who as early as 1889 published Die Waffen nieder! (Lay Down Your Arms), a widely read and still relevant antiwar treatise, for which she received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1905. Writer Hedwig Dohm’s biting 1919 antiwar testament “Auf dem Sterbebett” (On her deathbed) criticizes the open displays of “ardent patriotism” at the start of the war that incited the “millions of blossoming young people” to “gun down human beings that never did them any harm” and to “march themselves into their graves.” Similarly, artist Käthe Kollwitz confides in her diary on August 27, 1914, early on in the war, “Where do all the women who have watched so carefully over the lives of their beloved ones get the heroism to send them to face the cannon? I am afraid that this soaring of the spirit will be followed by the blackest despair and dejection.” Kollwitz lost her son Peter in WWI and commemorated him through her antiwar drawings and sculptures still famous around the world today.

The population in Germany and Austria in 1914 certainly expected an immediate victory, never imaging the four long years of war and untold destruction. Women who were left behind watched from balconies as troops paraded through towns or bid men, young and old, farewell at train stations. Soon they would contribute to the war effort themselves as nurses, ambulance drivers, spies, reporters, workers in munitions factories. Their war stories shed light on the ravages of the private sphere, the home that provided no emotional refuge as the letters from the front poured in and the shortages of food and resources turned daily life into an existential struggle, causing many a child to die.

In her novel Als die Männer im Graben lagen (When our men lay in the trenches), Käte Kestien provides a bleak depiction of the home front and specifically the challenges that working-class women faced: “Any kind of work that men suddenly had to put down, women learned to carry out […]. And all their other daily tasks remained as well. […] During the day, they worried about their children at home or on the streets, and their scant sleep was disrupted by their sorrows about the husbands and the brothers and the sons in the field. Then hunger was added, and now for the women every hour became a sometimes superhuman struggle with despair.” Notably, Kestien published this novel in 1935, intending to warn against the potential impacts of a new war as the Nazis gained momentum.

Considering the tremendous casualties of World War I (40 million total, 20 million of them dead, including 10 million civilians), few households were left untouched by the devastation. In Germany alone, 533,000 war widows were reminders of this personal toll of war, of Germany’s defeat, and of the traumatic wound that festered throughout the Weimar Republic (1919-1933). Yet, the widows’ experience – beyond the rhetoric of heroic sacrifice – was excluded from the public discourse in order to avoid deflating the war and then the postwar spirit.

While some authors featured fictional characters who mourned the loss of loved ones as mothers, wives, daughters and sisters, Helene Hurwitz-Stranz published numerous accounts of real-life women in Kriegerwitwen gestalten ihr Schicksal (1931, War widows shape their futures). A sense of growing self-reliance accompanies the sorrow these women express, and one widow states, “I realized suddenly, that it would be useless to hang my head. I had the courage to take my fate into my own hands.” The stories of women’s agency across generations were also taken up in works by authors of girls’ literature as a form of sentimental education and in the memoirs of nurses and journalists.

In addition, women’s voices from the distant colonies asserted their strong nationalist ties to the homeland and the burning desire to emotionally support and participate in the war effort from afar. The diaries of Frieda Zieschank, who resided in German Samoa in the South Pacific during WWI, reflect passionate patriotism that grew with the distance from the geographical motherland and emotional fatherland. Her writings express a sense of German superiority over the Samoan islanders and the occupying troops from New Zealand. Similarly, settler Frieda Schmidt’s personal papers from German East Africa exhibit nationalist competition with the British. Here, however, we observe a woman’s sense of painful humiliation when German citizens are stripped as enemies of war of their membership in the international colonial community of the white European elite.

What becomes clear when we look at the broad, yet still largely unexplored range of women’s writings is that no universal – Germany-related – female war experience or universal war (her)story exists. Rather, we encounter a multiplicity of viewpoints and constructions, shaped by factors like geographical locations in specific historical contexts, the experience of violence and loss, ethnicity, social class, marital status, religious beliefs, cultural traditions, ideological convictions and political engagement. The works of women authors all reflect a passionate engagement with the historical contexts and demonstrate how deeply personal the experience of war was and is.

Turning to the beginning of the twentieth century to review, interpret and reflect on the experience of war is essential for our understanding of how historical materials are deployed, exploited and provoked in many contemporary settings and how the past continues to influence the present. The histories of German colonialism and World War I live on today. Käthe Kollwitz’s Pietà now sits in the Neue Wache in Berlin as the central Memorial of the Federal Republic of Germany for the Victims of War and Dictatorship. Ricarda Huch’s essay on willingly destroying the famous Cathedral of Reims, France, if it advanced the German war effort, still haunts readers today when looking at the destruction of cultural treasures. The Herero and Nama are now seeking an official apology and restitution for the genocide from the federal government of Germany, the legal successor of the imperial government of the early 1900s.

Although much has changed in the last century, the fact remains that warfare has a massive impact on all involved, not just combatants. Reading women’s writings about war provides insight into the profound consequences of war – direct and indirect, short-term and long-term, at the front and on the home front. It makes us wonder: Where can we turn when even our home is no refuge from war?

This is the second article series from the authors. Read the first part here!

[Title Image by Namibia National Archives]