How to Digitize 68,000 Books Without Losing Your Sense of Humor

Transforming centuries-old books into a modern digital archive requires patience, precision, and the occasional kitchen utensil. Join our resident archivists Katinka Bratvold and Florian Hofbauer as they share the joys and surprises of preserving scholarship for future generations.

When De Gruyter and Brill joined forces in 2024, we set out to consolidate our centuries of combined print heritage into one digital resource, accessible across the world and far into the future. The result is the De Gruyter Brill Book Archive, which unites more than 68,000 titles from two of the world’s oldest academic publishers and their numerous renowned imprints.

The books in this collection tell remarkable stories of their own, but what about the hands that scanned and shelved the physical copies? Or the minds that tracked down missing titles and solved stubborn metadata mysteries? They have stories of their own, too, and we’re delighted to share them in this blog post. Billy Sawyers spoke to Katinka Bratvold, Director of Rights and Licenses, and Florian Hofbauer, Manager Processes and Digitization, who both played a key part in past digitization projects for Brill (Katinka) and De Gruyter (Florian), and who continue to work on digital archiving projects for De Gruyter Brill and Paradigm Publishing Services.

Billy Sawyers: To start, could you both share a little about your professional backgrounds and how you came to work in publishing?

Katinka Bratvold: I ended up in publishing by coincidence – probably like most people do. Twenty-five years ago, I joined Swets Information Services here in the Netherlands, which was a subscription agent. After almost fifteen years at Swets, I joined ProQuest – now Clarivate – and then Brill three years ago. It happened by chance, but it’s one of the better coincidences in my life. Publishing is such a nice field to work in.

Florian Hofbauer: Same for me. After studying library and information science in Hamburg, I sent out a lot of applications and ended up as a student assistant at De Gruyter. I was lucky that the other student assistant in the team left two weeks later, so I asked if the two student projects could be merged and then was offered a full-time position. That was eight years ago, and I’ve stayed ever since. It was my first job and it still feels like a good decision. Especially after the merger with Brill, it never gets boring – there’s always something new to learn.

KB: The merger itself has been one of the better things that’s happened. There are more colleagues, more exchange – it’s just more of everything.

FH: Yes, it’s been a really good match. Two publishing houses with long and very similar histories. It turned out to be a real opportunity for both.

KB: And this is just another reason to build a joint archive. These are really old companies (Brill is slightly older!) and our humanities collections run very deep and have aged well.

BS: Before De Gruyter and Brill joined forces, what kind of projects were you each working on?

FH: My first and biggest project was the De Gruyter Book Archive, or DGBA. In academic publishing we call them ‘archives,’ though technically they’re libraries – collections of books. I started out by literally shelving all the DGBA books and I learned everything from there. What destructive versus non-destructive scanning means, how to use metadata and manage duplicates. Some challenges were unexpected: How do we source titles that we no longer have access to? Do we have title lists? For all past years, the answer was no!

We turned an un-catalogued physical library – where no one really knew what was on which shelf – into eBooks on our digital platform. You can now search our system and find exactly where a title sits, physically and digitally.

“Some challenges were unexpected: How do we source titles that we no longer have access to? Do we have title lists? For all past years, the answer was no!”

That was the beginning. At the start of the pandemic, I moved over to the publisher partner team at De Gruyter [now Paradigm Publishing Services], but the task of cataloguing the archive is still ongoing. It’s a big workload. I also occasionally lead tours at the Berlin State Library (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin), where a large part of the DGBA is physically housed.

KB: I joined Brill as program manager for eBook collections, not to run an archive project. But four weeks in, I was told the project manager was moving roles, and that I’d be taking over this massive digitization project. I had absolutely no experience in sourcing old titles or managing metadata systems. But you just start. You learn by doing.

When I began, we had 3,000 books live on our website. We needed to reach more than 11,000 – each sourced, digitized, and checked. It was a steep learning curve, but also rewarding in so many ways. I built a dashboard to track progress, and watching the percentage of completed titles climb towards 100 percent was so satisfying. Much of our work isn’t tangible, but this was – you could literally see the results.

FH: Yes, the learning curve! We also went through this at De Gruyter, and now we’re able to use the big body of experience and knowledge to help us with smaller digitization projects at Paradigm.

BS: It sounds like the work combined very digital and very physical elements.

KB: We had an agreement with the Royal Library in The Hague, but they could only give us so many books per batch. The physical work of picking books from the shelves and packing them up required a lot of resources. To speed things up, we started purchasing old books ourselves. But of course, these books had been used and many contained pencil marks. Or, even worse, they had never been used and so their pages weren’t even cut.

So I brought in my sharpest kitchen knives, cookies, fruit, even a speaker for music, and my whole team sat together for hours cutting pages and erasing pencil marks. We used special electric erasers – like vibrating pens – to remove pencil without damaging the paper. And in two sessions, we eventually got through the work.

FH: That just goes to show how different the work can be in this field. Our data service provider makes those digital restorations for us; we send them the raw scans. But at Brill you had the magic pen! Maybe, in the end, analog wins.

BS: What are some of the biggest challenges in your work?

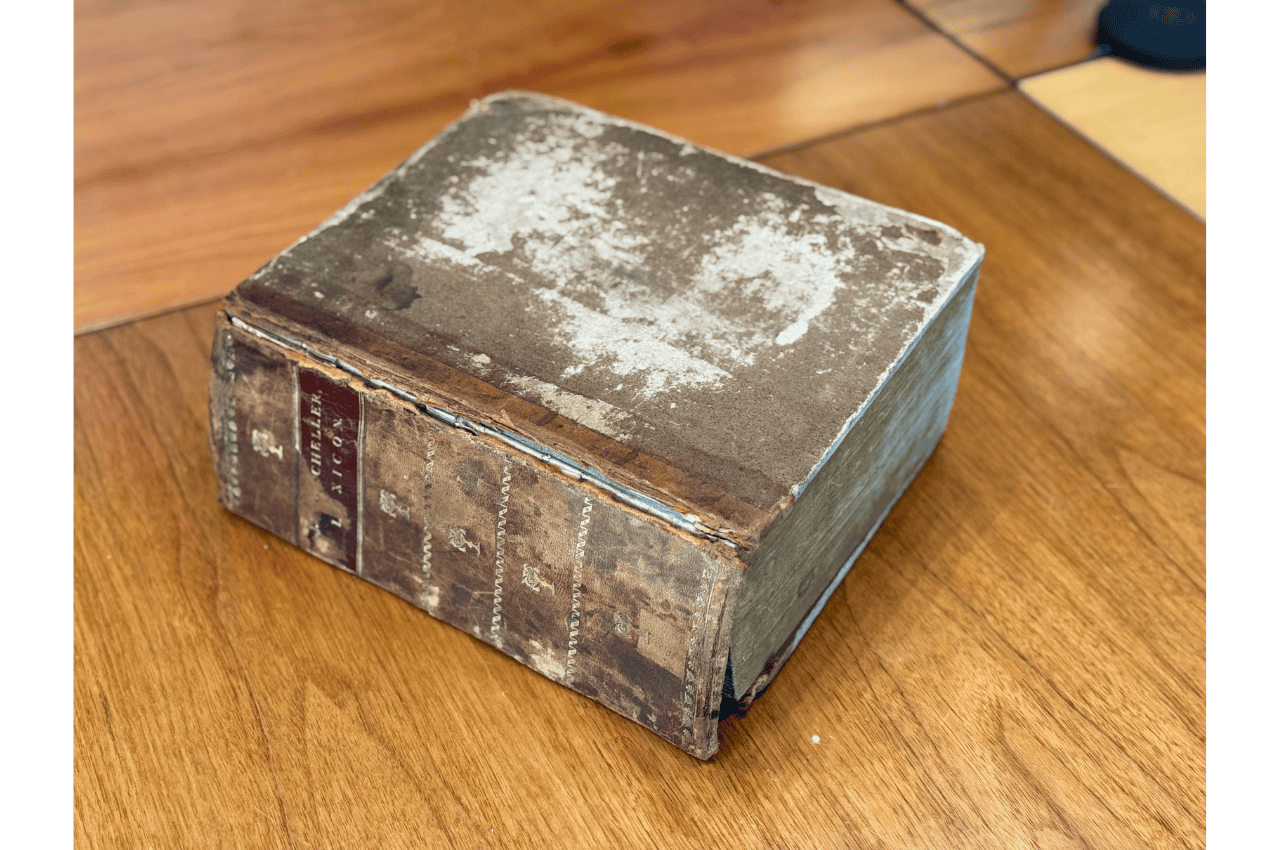

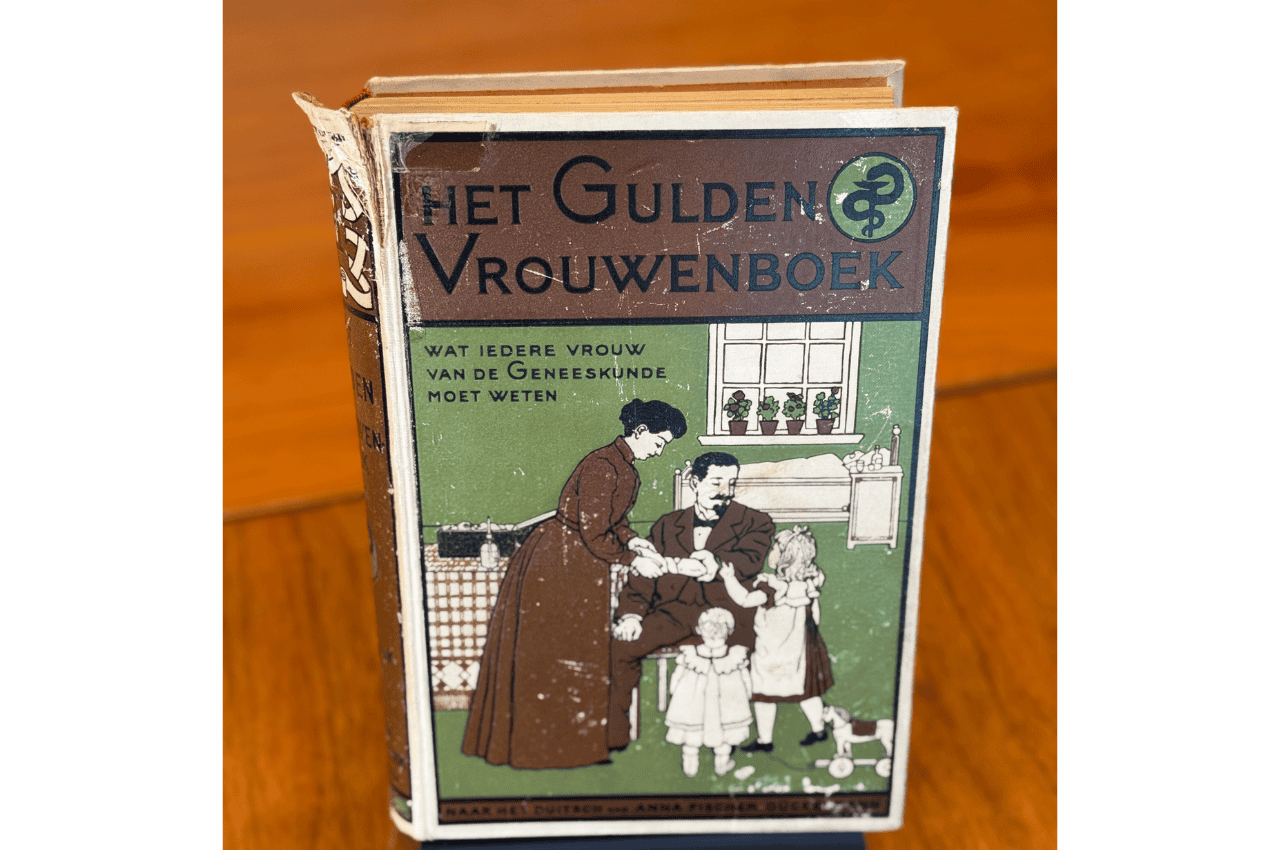

KB: Sourcing. Some of Brill’s books go back hundreds of years and belong to special collections – fragile, valuable, and nestled in special collections. The Royal Library and also the Peace Palace Library were fantastic partners, who were able to loan us a large number of books. But even then, security and preservation were complex issues. These books are precious to libraries as well.

But some of these titles aren’t in any libraries, and so we’ve also sourced second-hand books from across the Netherlands when necessary. Finding titles from 200 or 250 years ago is not easy.

“I brought in my sharpest kitchen knives, cookies, fruit, even a speaker for music, and my whole team sat together for hours cutting pages and erasing pencil marks.”

FH: For us, one challenge was balancing internal work with external vendors for whom we run digitization projects. What is the timeframe for the project, and how much detail is necessary? Metadata is a theme that gets more important the larger a project gets. Every digitized book needs a new ISBN, since it’s a new product. Some titles lacked consistent data, so we created unique internal identifiers.

Another issue was deciding what to digitize. In the 1960s–80s, print runs were huge, sometimes with five or editions of the same book in a single year. We debated whether to scan every edition and ultimately decided to digitize everything. Handling duplicates and cataloguing inconsistencies taught us a lot.

KB: Brill’s situation was different – we didn’t have an archive at all. We had some print files and some books stored in warehouses. We had to source everything else from scratch. All the books that we borrowed needed to be scanned non-destructively. Books that we bought could be scanned destructively, but sometimes we had books from the 1700s with leather bindings, and I just couldn’t bring myself to cut them apart. We kept those for marketing and historical display instead.

FH: When I talk about my work to other booklovers, they are always surprised that we have to get rid of so many books. But that’s how it goes. We had to accept the reality that not every book could be saved and stored physically. Destructive scanning means letting go of many copies, but the knowledge lives on digitally, accessible to many more people.

KB: Exactly. Our metadata process was the opposite of De Gruyter’s – we assigned eISBNs early and used them as unique identifiers. But we faced our own limits: our system couldn’t handle multiple editions, so we simply digitized whichever one we could find and moved on.

BS: For readers unfamiliar with those terms – what’s the difference between destructive and non-destructive scanning?

FH: Destructive scanning means you scan the book knowing it won’t survive the process. Non-destructive scanning is careful, page-by-page digitization that preserves the physical copy.

KB: With destructive scanning, you might literally cut off the spine and feed the pages through a copier – it’s much faster. Non-destructive scanning is slower but essential when working with borrowed or rare materials.

Further reading: Florian spoke recently with Allison Belan from Duke University Press about the importance of accessibility in digital publishing.

BS: What does your work look like now that De Gruyter Brill has become one entity?

FH: I now work in Paradigm, De Gruyter Brill’s publishing services unit. We digitize archives for other publishers – University of California Press, Yale University Press, Chicago University Press, and more. A personal highlight was working with the University of Pennsylvania Press to digitize the backlist of the American Philosophical Society, the oldest learned society in the United States. It was great to use our expertise to handle some of their oldest treasures.

This is the kind of archival work as you might imagine it from the outside – we wear gloves and document every step, every carefully-turned page. Our expertise in digitization now extends to ePub conversion and alt-text creation for accessibility, which has become increasingly important with the European Accessibility Act.

“Archives are like the external hard drive of a publishing house … all we have is the accumulation of knowledge written down in the past.”

KB: My main role now is Director of Rights and Licenses, overseeing translation rights, permissions, and the licensing of content to third parties. It’s quite different, but in fact it aligns with what I’ve done in the past, before joining Brill. I’ve kept the Brill Book Archive project because I’ve managed it for three years and I’m not quite ready to say goodbye to the project after working so hard on it. I’m really happy, though, to have new colleagues to support this work after the merger.

We’re now on the final stretch – about a thousand titles left. It’s probably my last digitization project, but it’s been one of the most rewarding experiences of my career.

BS: To close, could you each share what you think makes archives so important in academic publishing?

FH: For me, archives are like the external hard drive of a publishing house. Research is about understanding things in precise detail, or spending perhaps your entire career trying to answer one question. And to explain the world that we study, to look into the future, all we have is the accumulation of knowledge written down in the past.

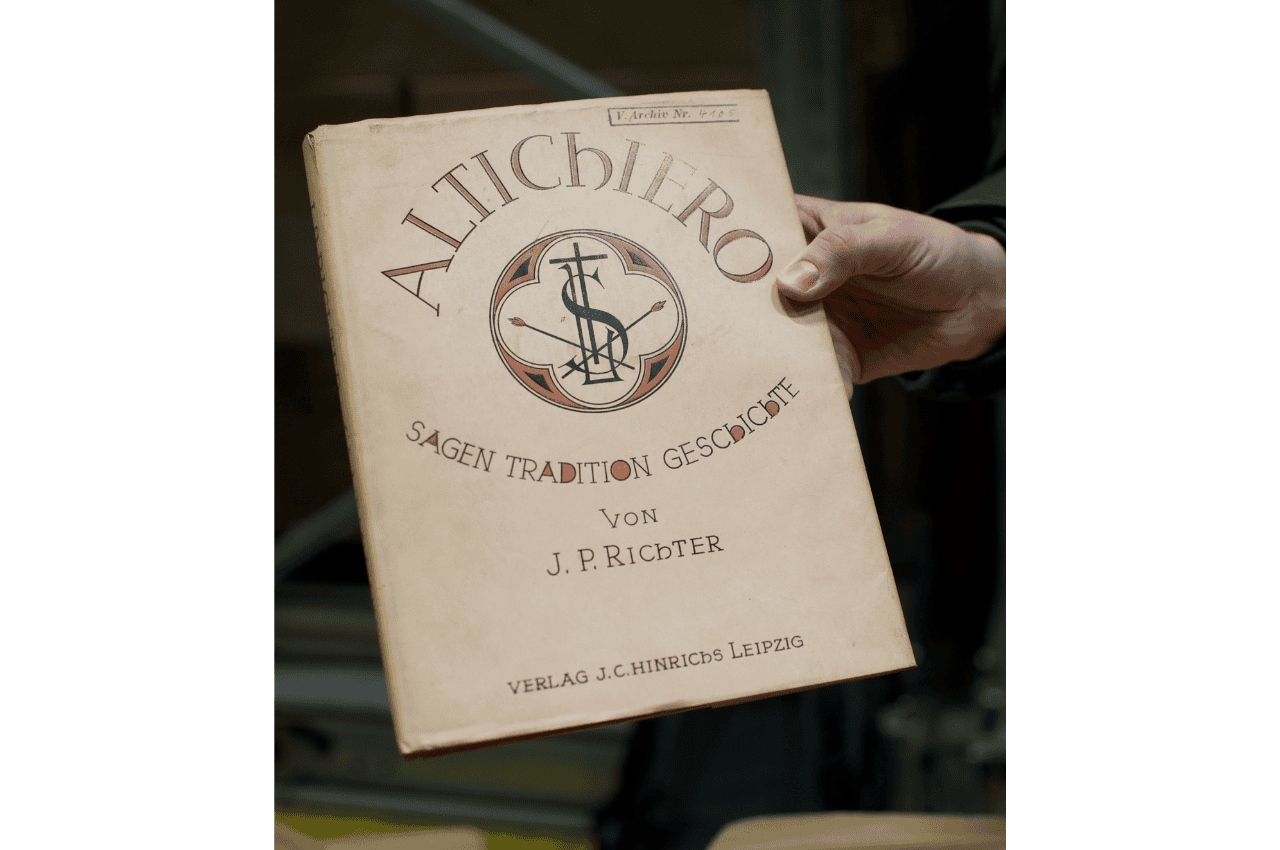

This exercise might look ridiculous at first. During the DGBA project, we digitized 1970s law books about road signs and wondered who would ever read them. Yet every single title ended up being downloaded at least once. That says everything. Every publication has value to someone, somewhere.

It should be the goal of every scholarly publisher to maintain a complete digitized archive. At some point, everything will be digitized, and it will be like a treasure hunt – there will always be forgotten pieces to rediscover, perhaps even through AI tools that help uncover connections in handwritten notes or in the margins. That’s why continuing this work matters.

“Books that can only be found in a handful of libraries are now available for everyone, everywhere, bringing this rich publishing history to life.”

KB: I agree completely. Digitization preserves history that might otherwise be lost and makes it accessible to a much larger audience. Digital documents can be magnified, listened to with text-to-speech tools, and accessed from all over the world.

This is a real highlight of the work for me. Books that can only be found in a handful of libraries are now available for everyone, everywhere, bringing this rich publishing history to life. Every time a physical book is handled in a reading room, it wears down a little more. Digital access protects those fragile originals while making their contents easier to search, cite, and reuse.

Books also reflect their time. Some titles we look back on now and think, we wouldn’t publish that today. But that’s exactly why archives are so vital: they show how thinking and language evolve. Making that record open to researchers is also important.

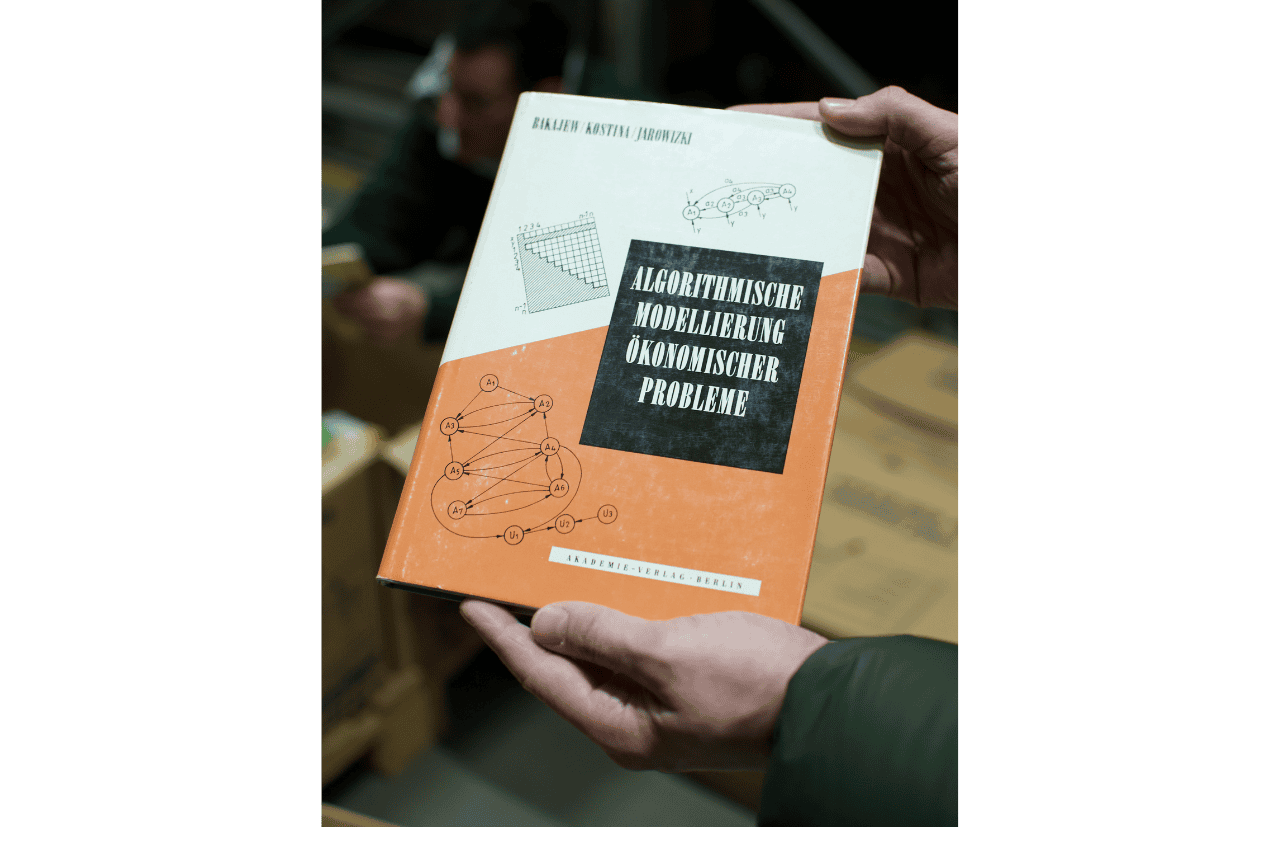

[Title Image by Alina Simmelbauer]