History as a Poetess: Stefan Zweig on Biography, History and Politics (1943)

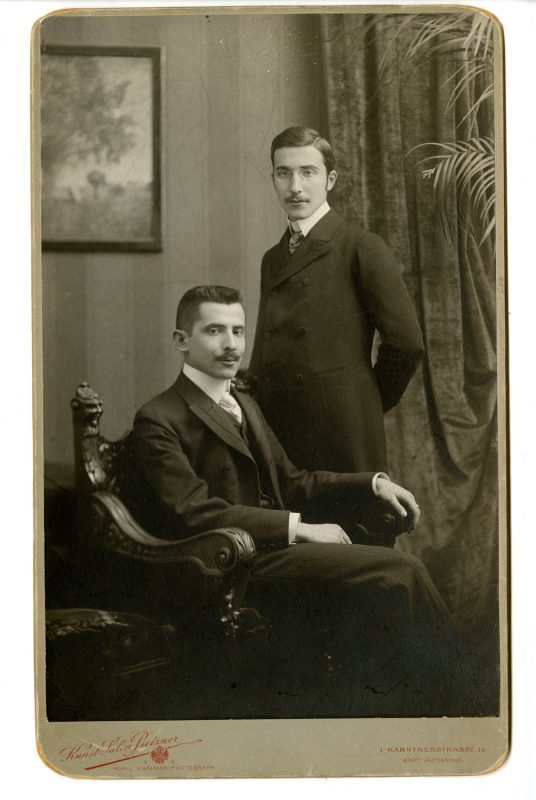

In 1939, Stefan Zweig prepared a lecture on history for the PEN Congress in Stockholm, but the event got cancelled. Published shortly after Zweig’s and his wife Charlotte Altmann's suicide in 1942, Zweig's essay is evidence of an attempt to spread optimism in bleak times. An excerpt.

Our very first encounter with history happened at school. It was there that we children were first informed that the world did not begin or end with us, but rather that all organic things had come into being, they were things that had become and grown. There had thus been a world long before us and another one before that.

In this way history embraced us and led us by our curious infant hands ever further back through the colourful picture gallery of the ages. She taught the child that we were, taught those not of age, that there was once an epoch in which the whole of humanity had been just as dependent and childlike, in which our ancestors lived in caves like newts, without fire or light.

“Step by step, history, the great teacher, demonstrated the tremendous path of humanity.”

But she, history, also showed, to our wonder and astonishment, how peoples were formed from these initial, diffuse raw hordes, how states crystallized, how from East to West, like a growing flame, the culture of one nation was passed to another and illuminated the world – step by step, history, the great teacher, demonstrated the tremendous path of humanity, the path from the Egyptians to the Greeks, from the Greeks to the Romans, and from the Imperium Romanum via a thousand wars and reconciliations to the threshold of our world today.

That was and that is the first, the eternal task of history, with which she met us in our school years: to visualize the course and the development of all of humanity for the young, developing person and to weave him, the individual, intellectually into a vast series of ancestors, whose work and achievements he should complete with dignity.

The Great Educator

As the great educator about the shape of the world – thus history met us all in our youth. But educator and teacher, she almost always wore a stern face. History appeared to us as a pitiless judge who, with a fixed countenance, without love and without hate, without judgement and without prejudice, recorded events with her iron stylus. She taught us to conceive of the immense chaos of world events as being ordered according to numbers and groups and we did not love her very much.

We had to – I believe this was true for everyone – learn history under duress, as a school subject, as an exercise, before we began to seek her out, to recognize and to love her of our own volition. Many things bored us and few things pleased us in the great chronicle of the world, even then in school years our attitude was not quite free of judgement and prejudice, of personal reference.

If we remember those school years precisely, then we also remember that we did not always read the chronicle of the world, as unrolled before us by history, with the same love or the same interest. There were long stretches and periods in those books that we read begrudgingly, without sympathy, without joy, without love, without passion, that we learnt just as one learns something required, something imposed, as one learns a ‘school subject’, but, I repeat, without inner joy, without the use of the imagination.

“There were long stretches and periods in those books that we read begrudgingly, without sympathy, without joy, without love, without passion.”

Then there came episodes in history that we experienced as passionately as adventures, single passages in books where we could hardly turn the pages quickly enough, where our innermost being, our most secret powers were impassioned, where our imaginations slipped into the admired figures themselves, where we lads felt like Conradin, like Alexander, like Caesar and Alcibiades. The difference that I am describing here is a shared experience.

Great Victors and the Heroically Beaten

I believe that the youth of every nation spontaneously chooses favourite epochs and favourite figures in history, and I even believe that in all countries and in all young generations such love and enthusiasm is directed towards the same figures and episodes. There are always great victors like Caesar and Scipio who stir the enthusiasm of young people, and there are always the heroically beaten, like Hannibal and Charles XII, for here the passionate sympathy intervenes that stirs every young person so beautifully.

In general, though, it is the same dramatic episodes of history that bewitch the twelve-year-old, the thirteen-year-old and fifteen-year-old, with the same effect in the North and in the South, in the East and in the West. And certain lively epochs of humanity, like the Renaissance, the Reformation, the French Revolution, have the advantage that they are impressed into our senses with an especial strength of imagery and three-dimensionality.

“History, as a teacher, as an unyieldingly just chronicler, is also sometimes a poetess. I say emphatically: sometimes.”

But it cannot be a coincidence that particular favourite figures and favourite points in history have remained similarly forceful for humanity since the days of Plutarch. Such a unanimous stirring of the imagination must have a particular cause. I see this secretly operating law, this reason, in the fact that history, as a teacher, as an unyieldingly just chronicler, is also sometimes a poetess. I say emphatically: sometimes.

Then she is not always one, not in continuo, just as no poet, no artist, is a poet uninterruptedly for the whole twenty-four hours of his day. Weeks and months are for the truly creative person often wholly idle periods in which he, citizen and journeyman, lives just as unproductively as every other; all excitement requires times of preparation, of collection.

Poetic power, like any other, has to accumulate before its first, strong attempt, it has to rest and collect itself in order to then emerge suddenly and victoriously. The visionary, the truly creative state cannot become a permanent, a normal state, whether for individuals, or for whole nations. And it would therefore be senseless if one were to demand, to demand oneself, ceaselessly and without pause, only great, exciting, shocking, moving figures and events from history, from ‘God’s mysterious workshop’, as Goethe called her.

History as a Poetess

No, not even history can constantly produce geniuses and towering, superhuman characters. She too has pauses to create tension, pauses for effect, and whoever wishes to read her like a detective novel, in which each chapter is loaded with the high tension of a revolver, offends the high spirit that presides within her.

We may thus conclude – history is not uninterruptedly a poetess, she is mostly only a chronicler, a reporter of facts. Only very rarely does she have such sublime moments, which then become the very same favorite passages, the favorite figures of each generation of young people – normally she delivers only a chronicle of facts, unformed world matter, a sober sequence of logically founded occurrences.

But sometimes, just as nature forms flawless crystals in her lap without human help – sometimes individual episodes, people and eras in history meet us with such high excitement, with such dramatic completion, that they are unsurpassable as works of art, and in them history as the poetry of the world’s spirit puts the poetry of all other poets and every earthly spirit to shame.

This is an excerpt from Stefan Zweig’s Essay “History as a Poetess” taken from the book Biography in Theory. Translation by Edward Saunders. First published as Stefan Zweig: ‘Die Geschichte als Dichterin’. In: Zeit und Welt. Gesammelte Aufsätze und Vorträge 1904–1940. Ed. Richard Friedenthal. Stockholm, 1943, pp. 363–388.

Interested in biography? Read Edward Saunders on Different Ways to Write a Biography, Gisela Holfter on the fascinating stories of German Refugees in Ireland, and our biographies of feminist icon Emmeline Pankhurst and business tycoon Lord Beaverbrook.

[Title Image by Roman Kraft via Unsplash]