Bred for the Reich: How the Nazis Enlisted the Animal World

Even as they orchestrated mass violence, Nazi leaders found time to obsess over cows. And dogs. And the perfect horse. Animals didn’t just decorate propaganda posters or pose beside dictators—they were drafted, trained, bred, and classified with chilling precision. What happens when a regime tries to reshape not only humans, but animals too?

The Third Reich’s animal policies weren’t about kindness. Forget the oft-quoted 1933 animal protection law. What mattered was control: of bloodlines, bodies, and entire species. Dogs were inspected like soldiers, horses ranked for “racial fitness,” and cattle catalogued as tools of national productivity. Some animals were Aryanized, others deemed unworthy. In the middle of it all, the SS was running a rabbit-breeding station inside Dachau.

The Dog Was a Soldier

In 1939, the German military began mass “musterings” – not just for men. Dog owners were summoned to state-run recruitment stations, where each animal was assessed for wartime readiness. Dogs were tested for obedience, aggression, trainability. A good German Shepherd could end up on the battlefield or guarding a concentration camp. A bad one? Not worth feeding.

Dogs, especially the Schäferhund, embodied loyalty and discipline, qualities celebrated as racial virtues. Propaganda showed upright dogs beside uniformed men, not as pets, but as comrades. In one striking case, the Wehrmacht newspaper Unser Heer praised a dog named Greif in the midst of the Battle of Stalingrad: “zäh und verbissen, treu und gehorsam” – tough, loyal, obedient. The perfect Nazi. But the closer dog and soldier came to merging, the more likely both were to die alike.

Cattle and Pigs in the Battle for Production

The regime was arguably even more obsessed with livestock. Pigs and cattle were vital in the Erzeugungsschlacht (battle for production), the campaign to make Germany agriculturally self-sufficient. This wasn’t just about food. Livestock was embedded in the racial ordering of society. Cattle bloodlines were tracked like Aryan pedigrees. Swine were judged by meat yield, cows for milk and both for “racial purity.” Regional breeds were idealized as “ur-deutsch,” and breeding mandates extended into occupied territories.

“Even the humble cow became a vessel for Nazi ideals of productivity, strength, and purity.”

By war’s end, livestock farming was a national duty and often a form of conscription. Rations were withheld from farmers who didn’t meet production targets. Certain breeds were “exhibited” as models of the Volksgemeinschaft. Even the humble cow became a vessel for Nazi ideals of productivity, strength, and purity. And even in concentration camps, animals were bred, not only for food, but also as symbols of hierarchy. Prisoners were meant to feel worth less than the animals around them.

Horses, Heimat, and the Myth of Endurance

If the cow was the worker, the horse was the dreamer, the ideological steed of the Thousand-Year Reich. Horses symbolized an idealized countryside: Heimat untouched by modernity, machines, or moral decay. Riding signaled rootedness in Blut und Boden, in nature and tradition. The horse, especially the Trakehner breed, stood for a fantasy of Germanic past and martial future.

Learn more about the historical relationships between humans and animals in our blog post “What is Animal History and Why Does It Matter?”

While the SS ran elite riding schools, Wehrmacht veterinarians produced reports on battlefield performance. Even the horse’s bearing and stride became political. The “proper” German horse was noble, strong, reliable, and never to be confused with the Panje horses of Eastern Europe.

Horses were also celebrated because despite tanks and mechanization, Nazi Germany depended heavily on them. Millions were conscripted for the war, pulling men, weapons, and myths across Eastern Europe. The Wehrmacht became one of the largest equine operations in modern history. In propaganda, the horse remained clean, heroic, and above the mud.

And then there were the fantasy creatures: Bison, aurochs, wolves. These weren’t just symbols. The Nazis tried to rewild parts of Eastern Europe with “pure” species, via pseudo-scientific programs led by ideologues in lab coats. Zoos in Berlin and Munich became ideological playgrounds. Here, animals were no longer just curiosities, but prototypes for a racialized natural order.

“Animals weren’t just props. They were metaphors, models, rehearsals.”

Why all this effort? Because animals weren’t just props. They were metaphors, models, rehearsals. The language of breeding and purity moved seamlessly from dogs and pigs to people. The logic was disturbingly fluid: If one could perfect a herd, why not a population? Animal breeding practices became test beds for eugenic thinking. They also supplied a vocabulary: “bloodlines,” “purity,” “degeneration,” “herd health.” These terms echoed from agricultural journals to racial hygiene reports. The overlap wasn’t accidental – it was foundational.

When Ideology Meets Mud and Manure

And yet, animals rarely fit their roles. Not because they resisted, but because biology, logistics and reality got in the way. Despite the idealization of German breeds, soldiers on the Eastern Front found that local Panje horses, small and sturdy, far outperformed the prized Trakehners in the Russian winter. The rustic Slavic steed became indispensable to the German war machine.

The same happened with dogs. As the war dragged on, the regime’s obsession with pedigreed German Shepherds clashed with need. In practice, “bastard” dogs – impure and unapproved – were drafted because there simply weren’t enough purebreds left. And the aurochs? Celebrated as the resurrection of a mythic Germanic beast, these animals were really the product of speculative back-breeding. They looked impressive in zoo enclosures, but biologically, they were just oversized cattle. More fantasy than fauna.

These weren’t acts of rebellion. They were the banal limits of control. But each mismatched dog, borrowed horse, or ersatz myth quietly revealed how much Nazi ideology relied on the illusion that nature could be molded into order.

More Than Victims, Less Than Symbols

This is not just a story about animal victims – though suffering was ever-present. Nor is it merely about Nazi kitsch: wolves on badges, deer in oversized oil paintings. Rather, it’s a story about how political systems embed themselves in the most mundane acts: feeding pigs, training dogs, counting cows.

The animals of the Third Reich weren’t just symbols. They were bodies, resources, workers, messengers, and sometimes obstacles. And if we take them seriously as historical subjects – not as stand-ins for people, but as creatures shaped by and shaping their world – we may better understand not only the Nazi regime, but also the deeper entanglement of biopolitics, violence, and taxonomy that runs through modern history.

Learn more in this related title

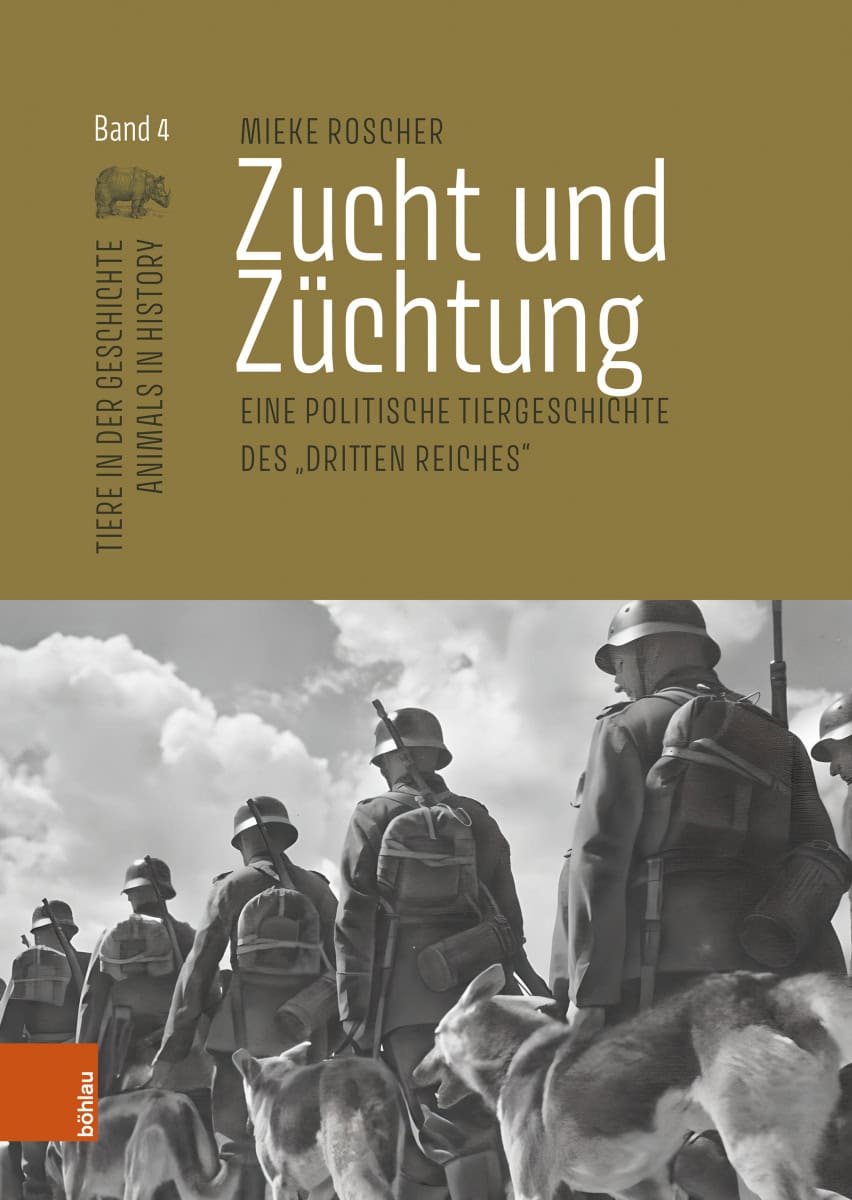

[Title image: German Federal Archives, Peter Adendorf, CC-BY-SA 3.0]