Ancient Ukrainian “Megasites” Might Have Been the World’s First Cities

Recent archaeological research from Ukraine is challenging long-held views on the beginnings of urbanism.

Ever since Gordon Childe’s research on the urban revolution, archaeologists and historians have accepted his conclusion that the first cities developed in the Fertile Crescent of the Tigris-Euphrates valleys in the 4th millennium BC. While proto-cities such as Çatalhöyük or Jericho caused some re-thinking, recent research in the Ukrainian forest-steppe zone has clarified the creation of huge sites larger and earlier than the first Mesopotamian cities. Can we call these Ukrainian sites ‘cities’? And, if so, do they belong to a specific and poorly recognised form of urban site – the low-density city?

‘The concept of “city” is notoriously hard to define.‘ This is the opening statement of Childe’s seminal article ‘The urban revolution’ (1950). Almost 70 years later, this task has become even harder, with urbanism attested in a far wider range of environments, cultural trajectories and material forms than were known to Childe. Yet the traditional global primacy of high-density urbanism in settlements in the Fertile Crescent has remained intact and untroubled by global difference.

“It is uncertain why cities should always go hand in hand with political and economic centralization.”

The second element of the traditional view is that Near Eastern urbanism was earlier than the first European city by two millennia. While Minoan statehood may be dated to 2400 BC, the 100 ha Late Minoan city of Knossos dates to the mid-2nd millennium BC, showing that states may have developed without cities. Later still, classic examples of European cities co-emerged with states in the 1st millennium BC in Greece, Etruria and Rome, while large, low-density, temperate European Iron Age centres, termed oppida by the Romans, have an ambiguous relationship to urbanism. This narrative enshrines the powerful tradition of equating urbanism with political and economic centralization. But it is uncertain why cities should always go hand in hand with political and economic centralization.

The other, more serious problem with the standard account is its exclusion of the largest sites in 4th millennium BC Eurasia, if not the world — the Trypillia Chalcolithic megasites of the Ukrainian forest-steppe. ‘Megasites’ were the largest Trypillia sites, defined as covering an area of 100 ha or more and reaching as large as 320 ha. Their local environment consisted of the North Pontic forest-steppe zone – a mosaic of deciduous woodland of lime, elm, oak, and hazel interspersed with open parkland in rolling loess plateaux rarely exceeding 250 metres above sea level, where some of the most fertile soils in Europe — the chernozems — had developed from the 5th millennium BC onwards. The Trypillia group were pioneering agro-pastoral communities which introduced domesticated crops and animals, large timber-framed houses, and a wide range of novel material culture to the forest-steppe zone.

Imagined Communities

It is easy to forget the unprecedented nature of Trypillia megasites. During the 5th and 4th millennia BC in Eurasia, Trypillia megasites were unique in size and scale. Nowhere else on the planet in 4200 BC compared to the megasite of Vesely Kut, in south-central Ukraine, covering an area of 150 ha. Such vast sites pose immense problems of explanation and understanding, but first of all, problems of imagination.

One of the hardest, and often unaddressed, questions for the creation of a new site type based upon unprecedented features (size, planning, etc.) concerns the role of imagination. In ‘Imagined Communities’, Benedict Anderson’s influential study of the anomaly of modern nationalism, the author reminds us that all communities larger than a single village were ‘imagined communities’, because separate communities have, by definition, never lived together with a second group. The anthropologist Maurice Bloch recently expanded the use of the term ‘imagined communities’ to beyond the political framework, suggesting that wide, self-defining groups exist because they are ‘imagined’, whether as descent groups or religious groupings.

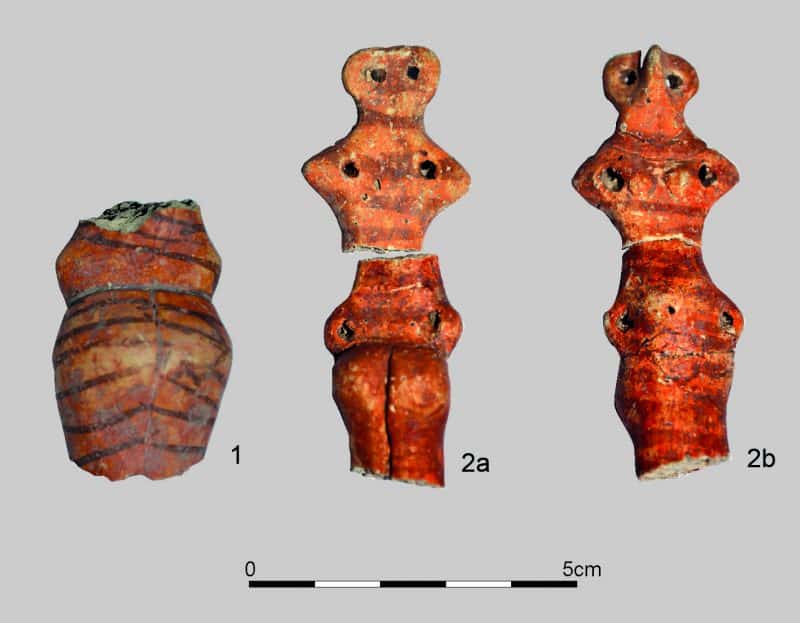

Imagined communities could have taken root in the Trypillia network at three different spatial levels: the individual settlement, the descent group whose members spanned two or more settlements, and the largest scale of total cultural distribution. For the imagined community of early megasites, we suggest that the first step of the integration of people beyond their normal, face-to-face groups depended on their shared use of a closely related suite of houses, painted pottery, and miniature fired clay figurines found which had vast regional variations. This led to compatible behaviours between communities over large areas and enabled better co-operation once they started to live together.

But a leap in the dark was still required: until diverse communities tried to live together, local Trypillia settlement groups could not tell whether the new settlement form would bring more benefits than the problems of living together. After all, there is a long tradition, emphasised by Childe, of the advantages of living in independent, face-to-face communities, which put a long-term brake on the scale of settlement nucleation in prehistoric Europe.

Understanding the Megasite

The most complex issue for any project seeking to confront Trypillia megasites is the issue of scale. Just as Trypillia megasites posed the problem of how 5th millennium communities could imagine a site 10 — 20 times the size of what they habitually built and occupied, the question of scale confronts each project with logistical, methodological and sampling issues of how to investigate such massive sites, such huge landscapes. We found this to be an ever-present issue in the collaborative Anglo-Ukrainian investigations of the Nebelivka megasite, near Novoarkhangelsk, in Kirovograd County, in south Central Ukraine (2009–2016).

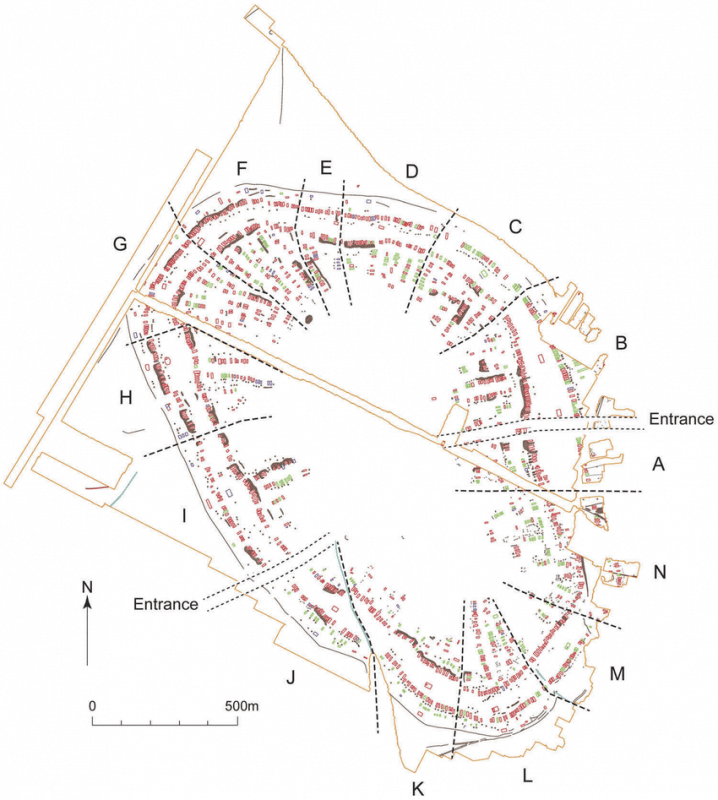

It is impossible to conceive of any progress towards understanding these huge sites without the introduction of modern geophysical techniques of investigation, which have allowed the production of plans of vast settlements more quickly than ever before. While major parts of the megasite plans have been produced at Taljanki and Majdanetske, the Nebelivka Project has produced the only complete megasite plan so far, with a site area of 238 ha inside a shallow perimeter ditch.

All of the principal planning elements recognized in the first stage of megasite research in the 1970s and 1980s have been confirmed at all investigated sites in this second stage (2009 onwards): the multiple concentric house circuits separated by large spaces, the inner radial streets leading to an open inner space, and the high frequencies of burnt houses and lower totals of unburnt/poorly burnt structures. In addition, recent geophysical research has identified several new classes of anomalies: unburnt/poorly burnt houses, pits of differing sizes, large structures interpreted as public buildings, industrial features—kilns or cooking facilities, perimeter ditches, garden areas, palaeo-channels and pathways, as well as new combinations of elements (Neighbourhoods, Squares and pit lines/groups). These new elements and combinations enabled the creation of a much more dynamic narrative of megasites than was previously possible.

The centre of each megasite comprised a large open area with no evidence for building or deposition. The 105 ha open space at Nebelivka formed an area so vast that it could have contained almost any previous Trypillia site. Monica Smith has demonstrated how open areas were active participants in the social space of complex sites, carefully managed and often with seasonal changes in function. The significance of the inner open area for major megasite ceremonials and regional-scale meetings has been overlooked in previous research.

Bottom-Up Planning and Deliberate Destructions

At first sight, the regularity of any megasite plan suggests a hierarchical social order, with the power to impose a site-wide plan and control house-building in a regular layout. But the new geophysical investigations at Nebelivka show that this regularity is deceptive, with as many as 18 different forms of variability in plan detail. This heterogeneity was seen in major plan elements, such as the distance between the outer and inner house circuits or the length of uninterrupted perimeter ditch sections, as well as minor planning elements, such as the presence and alignment of kinks in house circuits or the presence/absence of blocking streets cutting off radial streets from the inner open area. This high level of variability is a strong indicator that the Nebelivka plan was created from the bottom up rather than imposed hierarchically from the top down.

The improved resolution of Nebelivka’s geophysical plan enabled a more structured interpretation of social space, with two additional levels between the levels of the house and the entire site — the Neighbourhood and the Quarter. Neighbourhoods consisted of linear groups of adjacent houses – the intimate framework for living together. The larger unit of the Quarter took the form of pie-slices from the centre to the outer edge of the megasite, including many Neighbourhoods and often two structures which were larger than usually dwelling houses. We have termed these ‘Assembly houses’ and maintain they were the foci of Quarter-wide ritual to integrate the social lives of those living in the Quarters.

Two-thirds of Nebelivka houses had been deliberately burnt to a high temperature at the end of their use-life, with the remainder weakly burnt or unburnt. The experimental finding that five to ten times more timber was required to burn a house as to build it confirms the notion of deliberate burning and has major implications for landscape impact. The burnt remains of about 10 per cent of the houses formed a low mound, visible on the surface. Steady accumulations of what we term ‘memory mounds’ across the site turned Nebelivka from a dwelling site to a mixture of settlement and ‘burnt house cemetery’.

“The majority of remains show how a series of interventions brought together a wide range of people in deliberate acts of deposition and destruction.”

The Nebelivka excavations showed an archaeology of selective fragmentation and episodic discard and deposition. Residents regularly broke their pots and figurines and deposited parts of an object in one place (maybe a pit) and parts of the same object in another place (perhaps a burnt house). While the discard of food refuse and debris from stone tool production showed local activities, the majority of remains do not provide a direct reflection of daily lives, a ‘living assemblage’. Rather they show how a series of interventions brought together a wide range of people in deliberate acts of deposition and destruction, such as the unusual (but not rare) event of a house-burning. This means that the deposited finds show us the contributions made by different households to the ‘house death assemblage’, as a way of expressing inter-household relations.

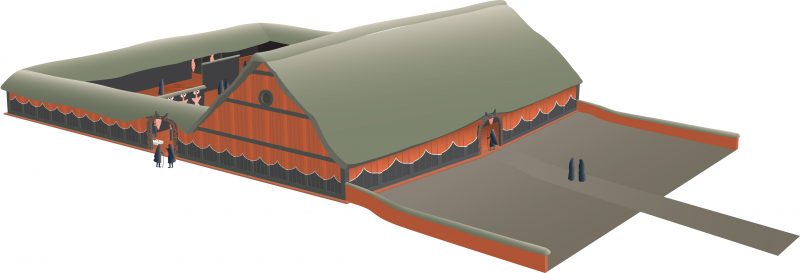

The scale of depositional acts at Nebelivka ranged from the single event, such as an episode of placing fragments of two vessels in a pit fill, to the massive communal ceremony of the burning of the megastructure — the largest Assembly House at Nebelivka and, at 33×20 m, the largest Trypillia structure yet found (see image below). The megastructure deposition involved the placement of over 60 kg of broken pottery derived from at least 332 vessels—the majority for communal consumption, with differences in pottery fabrics indicating ‘gifts’ from many different households.

Innovative Trypillia

Three key innovations affected the growth of Trypillia settlements: the creation of coherent settlement plans, the introduction of painted pottery, and changes in the importance of animal husbandry. Changes in settlement planning led to the novel combination of planning elements into a single coherent megasite plan. The creation of two new types of large vessel widened the scope of household grain storage and communal consumption and feasting. Decoration of fine wares in black paint required an expansion of exchange networks to obtain exotic manganese pigments from the Carpathians, some 250 km away to the west.

The combination of these changes led to a new class of fine painted wares, leading in turn to novel opportunities for domestic and public acts of deposition. The intensive rearing of domestic animals (over 90 % at Nebelivka) gave households a greater control over animal keeping and wider opportunities for feasting; killing a cow provided up to 400 kg of meat – far too much for small household feasts but ideal for a large megasite ceremony. It was the integration of all three sets of practices at megasites that enabled scalar transformations in the quantity of people involved, the quantity of material involved, and the quantity of house-building and -burning involved. The sum total of these advantages led to the attraction of megasite lifeways to a wider pool of people living in the extended Nebelivka network of a 100 km radius.

Human Impact at Nebelivka

Anyone would imagine that this intensive activity at Nebelivka would have left a large human impact on the local landscape. However, to our surprise, the analysis of a 6 m sediment core from a valley 250 m from the edge of the megasite showed quite the opposite. The dated sequence of local vegetation showed traces of cereal pollen and a charcoal peak indicating intensive landscape burning pre-dating the megasite occupation but only a modest human impact on the landscape at the time of the megasite occupation. None of the five proxy records — deforestation, cereal pollen, micro-charcoal counts, soil erosion, and water quality — showed more impact during the megasite occupation than before or after it.

There is, thus, a paradox at the heart of the Trypillia megasites. On the one hand, the megasites constituted the largest settlements in 4th millennium BC Europe, with site sizes up to 320 ha and estimated numbers of houses of almost 3,000 on one site. Their size, distinctive concentric settlement planning and signs of social complexity have reinforced the notion of massive, permanent, long-term dwelling.

“There is a mismatch between the interpretation of a massive, permanent, long-term urban settlement and the environmental and material cultural evidence.”

On the other hand, there is little evidence for the material or social differentiation one might have expected from such remarkable settlements. There is a distinct rarity of prestige goods, especially copper metallurgy, marine shell ornaments and finely polished stonework. Moreover, there is no evidence for a strong human impact on the local forest-steppe environment which would have followed from such postulated intensive dwelling. In short, there is a mismatch between the interpretation of a massive, permanent, long-term urban settlement and the environmental and material cultural evidence for a very different form of dwelling — smaller, less permanent and perhaps seasonal. But can such a smaller, perhaps seasonal site be called ‘urban’?

Urban megasites in the Eastern Europe Forest-Steppe?

Most authors even today consider megasites as ‘large villages’, with none of the core traits of Childean urbanism and no urban legacy. However, advancing a relational approach rather than a Childean check-list compilation provides a new perspective on the urban debate. The core premise of the relational approach is that various categories of sites, including urban, emerge in relation to each other rather than absolutely. Thus, for example what constitutes a city (or a town) in 2nd millennium BC China could not and should not be a mould applied to large ad eleventh-century North American centres, such as Cahokia. Most definitions of what is ‘urban’ flatten emerging phenomena, developed cities and sites with a long urban legacy into one single ‘idealized’ view of what should be considered as urban.

The relational approach looks for emerging and recurring categories of sites in relation to preceding and contemporary settlement patterns. The difference, then, is not measured by presence/absence, absolute numbers or on a gradient scale, as others have done, but by identifying meaningful local markers for the key social phenomena in larger and smaller sites. The characterization of the category ‘urban’ in the Trypillian context in general, and Nebelivka in particular, has nine constituents — the territory to which a site is central, site size, population numbers, population heterogeneity, the concentration of skilled labour and management, the built environment and formalized spaces with special functions, the scale of subsistence, the potential to be a node and re-distribution centre in a wide-reaching exchange network and the overall social structure.

The small (4.5 ha) Trypillia settlement of Grebeni was selected as a representative site for comparison with the 238 ha Nebelivka along these nine lines. This comparison would not only point out obvious contrasts in scale but also demonstrate the profound difference in lived experience and a wide range of social and technological potential on the two sites. The social, economic and personal implications of living on a small 4.5 ha and the rare >150 ha sites are so different that there was no possibility that the Nebelivka megasite was simply a very large example of a typical small rural settlement. Such an equation would be a categorical mistake, of the kind which suggests that aircraft carriers are simply very large examples of yachts. We argue that megasites were perceived, experienced, and functioned in a very different way from any smaller previous and contemporary site.

“The Trypillia megasites were not only the earliest known urban sites in the world, but also the earliest known low-density urban sites in the world.”

It is not just Trypillia megasites that have suffered an oversight in global urban debates. It is only in the last 10 years that the significance of a certain class of sites has finally been recognized. In contrast to the classic high-density cities such as London, Paris and Berlin, low-density urban sites displayed variable population densities across their much larger area. Low-density urbanism was initially recognised by Roland Fletcher and is now an acknowledged alternative trajectory of urban development in most regions in the world. In terms of modern city growth, low-density cities are expanding faster than any other form of city. The Trypillia megasites share all of the principal characteristics of the low-density urban sites. This means that the Trypillia megasites were not only the earliest known urban sites in the world, but also the earliest known low-density urban sites in the world.

What really made the difference in the development of the world’s first low-density urban forms was the co-emergence of the megasites with the potential for an unprecedented scale of interaction — whether personal (exchange, feasting) or institutional (alliance formation). This conclusion suggests we have to reassess the history of global urbanism. Instead of a single process of the emergence of high-density urbanism in the Fertile Crescent, we can now detect two pathways to early urbanism – a high-density pathway in the Near East and a low-density pathway in the Ukrainian forest-steppe. This twin approach allows us to place the Trypillia megasites into their proper urban context for the first time.