World War II Museums and the Battle for Memory, 75 Years Later

In 2020, can we make a universal claim that the end of the Second World War in Europe was a liberation, a symbol of peace and freedom? A plea for multi-faceted approaches to remembering World War II.

In 1985 the West German Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker maintained that May 8th was the anniversary of the liberation of all Germans “from the inhumanity and tyranny of the National-Socialist regime.” Thirty-five years later, with the upcoming 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe on May 8, 2020, the idea that the end of the war is a day of celebration instead of defeat is commonplace in Germany.

It seems that the complexity of suffering, defeat, and perpetration of the war has been replaced by an almost completely positive reading of the war’s end, leading towards a prolonged period of peace. Politicians across the West will give speeches that mark Germany’s unconditional surrender as an act of liberation for all of Europe, including the Germans, guaranteeing peace and freedom for humanity.

The city of Berlin has marked the 75th anniversary of the war’s end (in Europe), as Day of Liberation from National Socialism, a public holiday. It has planned a street party and an open-air exhibition (pending cancellations of mass events because of the COVID-19 virus). Berlin’s senator for Culture and European Affairs, Klaus Lederer, notes that the events around the Brandenburg Gate will be “an unambiguous signal against Fascism and war.” In other words, while the war’s end is read as a liberation, its celebration in Germany, nevertheless, comes with a pedagogical mission and warning: its commemoration is thus being used to defend German and European societies against fascist and racist tendencies.

Different Meanings and Memory Battles

If one looks East, however, the interpretation of the war’s end and the relevance of anniversaries changes. Contemporary Russia celebrates the war’s end on May 9 as Victory Day. However, in the eyes of many former Soviet Bloc countries, the Soviet period is often understood as a second occupation. In this narrative the Soviet Union prolonged, rather that ended, the war. In other words, whether the end of the war is seen as beginning of a prolonged period of peace, marked by the development of human rights and European unity, or whether a true shift only happened with the end of the Soviet Union in 1991, depends on the dominant narrative.

For example, the different meanings assigned to the war have recently intensified in heated debates between Russia and Poland as well as the Baltic States. Polish and Baltic narratives emphasize the agency and guilt of Stalin and the Soviet Union as Hitler’s and Germany’s partner in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact from August 23, 1939. Whereas this quickly leads in East European memory to views of the Soviet Union and of Nazi Germany as equal totalitarian perpetrators of the war, Western narratives often downplay this tension; the Soviet Union becomes a partner of the Western Allies. After the war, the narrative becomes antagonistic again and shifts to the East-West dichotomy of the Cold War.

The government of Russian President Vladimir Putin has tried to reverse both narratives by arguing that Poland was partly responsible for starting the Second World War because it colluded with the German plans to dismember Czechoslovakia in 1938. Both countries’ memory politics are interested in a nationalization of Second World War memory that increasingly counteracts any universal memory of the war.

“The current memory battles about the interpretation, responsibilities, and causalities of the Second World War clearly demonstrate its relevance in contemporary society and politics.”

The current memory battles about the interpretation, responsibilities, and causalities of the Second World War clearly demonstrate its relevance in contemporary society and politics. As the living memory of the Second World War fades, the museum has become an increasingly significant medium to connect past and present. Similar to commemoration events and official memory politics, museums can reflect the cultural memory of current societies while also advancing and changing our knowledge and interpretations of the past.

In recent decades, the museum has become a medium of remembrance, one with the strong potential to tell one or multiple compelling stories. Those stories can help to commemorate or remember the war, to understand it, or to experience it, bringing visitors closer to the past. Visitors enter and fill a space; they connect as cognitive and emotional entities to the past; they become experiencers of the past. On the one hand, a museum can manifest a specific reading of the past that makes visitors believe in the factuality of this very specific perspective. On the other, it can help visitors understand the perspectival structure of war and that any narrative of the war’s meaning is constructed.

World War II Museums: Mediums of Remembrance

A history museum appears to most visitors as an authority that reports historical facts. This authority allows museums to not only represent the cultural knowledge of their time, but to shape visitors’ attitude towards the past and the dominant narratives and interpretations of it. The Warsaw Rising Museum (2005), for example, uses an apparently factual and objective style in its text panels, when describing the realities of the Warsaw Uprising in 1944.

The exhibition uses facts to skillfully stage a heroic narrative of the Warsaw Uprising, as well as to imply that this narrative is the only way to tell the story of the Uprising. Other perspectives – for example, questioning the logic of the Uprising – are indirectly marked as distortions of history. Visitors experience an emotive sub-narrative that holds the potential to manipulate them into blindly supporting the heroic deeds of the insurgents, celebrating national resistance and sacrifice.

The House of European History in Brussels (2017) portrays National Socialism and Soviet Communism squashing the weak democracies of Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, leading to an all-encompassing total war. The exhibition presents the Second World War as both the ultimate human catastrophe and an event that lays the foundation for the rise of peace, human rights, and European integration. Consequently, it becomes difficult for visitors to differentiate historical contexts of war victims, since every individual seems to suffer the same fate.

The conflict between a universal and cosmopolitan European interpretation of the war’s end and a nationalistic-antagonistic one is best exemplified by the memory battles in Poland around the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk in 2016 and 2017. The museum opened on March 23, 2017, after an impassioned memory debate centering on whether Polish public history should follow a nationalistic-heroic trend of establishing a post-Soviet Polish identity, or whether it should encourage a transnational pro-European discourse.

Whereas a universalist European narrative reads the war’s end as a warning to prevent similar suffering in contemporary conflicts, a nationalistic approach crafts a story of Polish resistance and survival. Here, the Warsaw Uprising led straight to the Polish Solidarność movement in the 1980s and the end of Communism in Eastern Europe.

The original museum leadership led by founding director Paweł Machcewicz created a museum that sought a careful balance between telling a national story of Poland’s involvement in the war and a transnational narrative of the universal impact of war on human civilization. Conversely, the new museum leadership, with government protégé Karol Nawrocki inaugurated as director less than two months after the opening, in May 2017, has exclusively emphasized the heroic Polish perspective highlighting Polish heroic acts of resistance as well as acts of brave kindness in helping their Jewish neighbors.

One of the original installations, which continues to be part of the permanent exhibition, lets the visitor enter a narrow hallway, in which three large swastika banners are displayed to the left and nine large rectangular Soviet flags to the right. Like threatened and resisting Poland, visitors must also walk between the menacing symbols of the two totalitarian regimes. They are dwarfed by the two large installations and placed in a position to empathize with the Polish role of being caught in the middle. Thus, the museum emotionally prepares visitors for its larger narrative of the war as a Polish path to resistance and survival.

At the end of the exhibition in Gdańsk, originally, visitors encountered a film installation, where two screens were split by an iron curtain, showing iconic photographs of historical events that occurred post-1945. When the events depicted in the film reached the twenty-first century, the two screens merged and showed the destruction of today’s Syria, indirectly asking the visitor the question: Why is this destruction, this human suffering, reoccurring? The museum connected past and present and consequently, the war’s end remained open.

“The new film The Unconquered manipulates the visitor towards a singular emotional response to war’s outcome.”

The new museum leadership immediately changed the film upon their takeover. The new film The Unconquered manipulates the visitor towards a singular emotional response to war’s outcome. In order to do so, the film uses the visual style of a videogame to tell the story of a Poland that – attacked from two sides – resisted and survived two dictatorships between 1939 and 1990. All Polish people, ‘unconquered’ and full of valor, have become a single collective within an emphatic ideological framework.

In contrast, the Bundeswehr Museum of Military History in Dresden (2011) creates multiple perspectives on the end of the war and its memory that are spread throughout the permanent exhibition. For example, one display cabinet entitled “Silent Heroes – Suppressed Memories” reinterprets the traditional notion of the war hero: Lieutenant Colonel Josef Ritter von Gadolla, the military governor of Gotha, was ordered to defend the town at all costs. Instead he arranged the city’s unconditional surrender to American troops and saved many lives.

In another section, visitors see a charred typewriter from an office in the Führerbunker in the Reich Chancellery. In itself, the object points to the violence and crimes committed and possibly written on this particular object, while at the same time indicating the end of the war and thus of violence. Close-by hangs a painting of a Saxon general from the nineteenth century. Soviet soldiers punctured the canvas with their bayonets in 1945, which, according to the museum, was a sign of their victory over the dictatorship and German militarism, but it also indicates a new form of violence brought about by the end of the war.

Here and throughout the Bundeswehr Military History Museum, visitors are challenged to grapple with multiple voices and interpretations. Rather than a linear interpretation of the end of World War II as bringing peace, numerous constellations of war and violence throughout human history are presented to the visitor. Thus, they are immersed in complex structural experiences of the past.

In The National WWII Museum in New Orleans, visitors find a different approach to the end of the war in Europe. They become immersed in an outdoor scene of destroyed Germany, containing large posters of German cities in ruins. These posters are mounted between staged remnants of ruins that appear to be still burning. Visitors can sit among ruins and watch a film about the defeat and liberation of Germany through the gaze of an American soldier. The combined representation of all American soldiers together allows the visitor to empathize with their mission to save the world from evil, their composite beliefs, and the challenges they faced.

Such immersive story-telling draws visitors into a narrative from which it is hard to distance oneself. Shades of experiences and multiple layers of storytelling disappear in favor of the perception of one ideological reality.

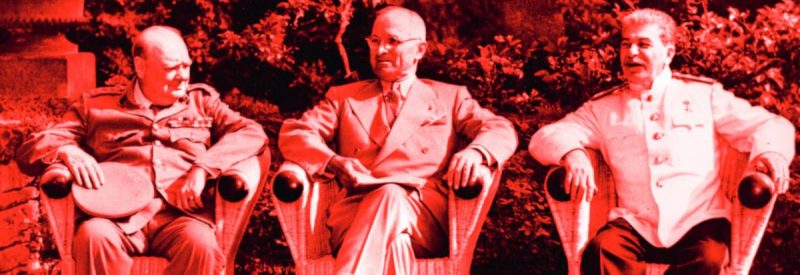

On May 1, a special exhibition will open on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the Potsdam Conference at Cecilienhof Palace. It will run until 1 November 2020. Instead of locating the meaning of the Potsdam Conference in a narrative framework that interprets the results of the conference leading to peace, the Cold War, or to the Soviet occupation of Eastern European countries, the organizers aim to immerse visitors in “a multi-medial journey back to these fateful days in the summer of 1945.”

The exhibition’s objective is to present a “factual, ideology-free, presentation regarding the geopolitical decisions made” in contrast to “the moving and emotion-filled voices of those affected. Famous historical personalities such as Churchill, Stalin, and Truman stand opposite history’s countless ‘nameless’ – including victims of atom bombs, displaced persons, and collaborators.”

If successful, such a multi-faceted approach will allow visitors to reach diverse conclusions about what the end of the war and its direct aftermath mean for our present understanding of the course of history. Instead of enshrining one meaning, visitors can understand how different meanings are produced and empathize with multiple perspectives across different national and social groups. They can evaluate personal and political decision-making and understand why a certain interpretation works for one individual, but needs to be adjusted for another.

Only if an exhibition puts the visitor in the position of an experiencer, so that the experience and possibilities of thinking and acting in the past and the present collide at certain points, can the visitor understand not only how historical facts but also how experiences and memories are constructed. Since the museum visitor can never completely take on the role of a historical individual or collective, it is crucial to understand the different techniques that museums offer their visitors in order to cognitively and emotionally connect with the Second World War from their unique positions between past and present. Visitors can learn that the meaning of the past is not stable, but rather constantly reconstructed.

Learn more in this related title from De Gruyter

[Cover image © MHM/Andrea Ulke, 2019]