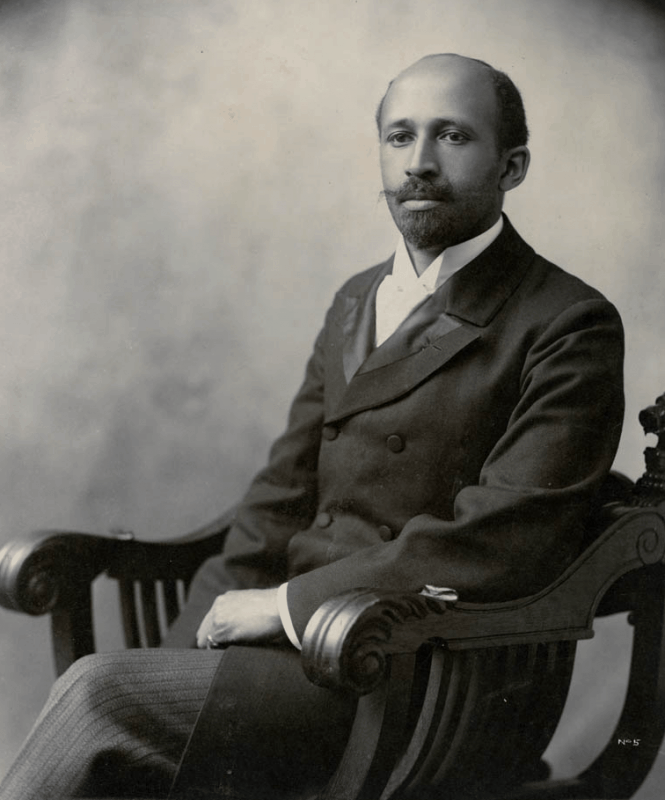

W.E.B. Du Bois: Biography of a Civil Rights Activist

Historian and sociologist William Edward Burghardt Du Bois is one of the most important African-American activists of the 20th century. He was a prolific author and public intellectual and co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

This article is an excerpt from John M. Reilly, Novelists and prose writers, 1979. It is one of the over 8.5 Million biographical sources included in the World Biographical Information System Online Database.

At the age of 35, in 1903, W.E.B. Du Bois took intellectual leadership of those within the Afro-American world who preferred liberal idealism to compensatory realism. Du Bois was prepared for his role by rigorous training in the traditional liberal arts as well as the newer empirical social sciences. But it was confidence and the moral absolute of truth and a poetic imagination that were to prove the sources of his effectiveness.

Leaving His Mark

Souls of Black Folk, the book in which Du Bois publicly announced his differences with Booker T. Washington, is constructed from first-hand observation, historical research, and reasoned analysis. Its power, however, derives from the images of divided consciousness (souls), a culturally united black nation (folk), and the veil behind which black remained nearly invisible.

“Du Bois’s metaphors represented intellectual liberation, giving blacks a profoundly dignified way of conceiving their own lives and history”

In a time when Jim Crow shaped perception as much as policy, Du Bois’s metaphors represented intellectual liberation, giving blacks a profoundly dignified way of conceiving their own lives and history. The cultural nationalism of Souls of Black Folk had been implicit in the earlier study The Philadelphia Negro, where Du Bois documented class structure and shared institutions. It reappeared as motivation for the Utopian vision of agricultural cooperatives in Quest of the Silver Fleece and the romantic narrative of worldwide organization for colored people in The Dark Princess.

Du Bois and the Harlem Renaissance

Du Bois’s well-known commitment to the idea of leadership by a talented tenth has its counterpart in the learned rhetoric of his essays and the grandiose design of his novels. It is no wonder that writing as a critic in Crisis he was unsympathetic to the experimentation and modern realism of the younger generation in the Negro Renaissance. Still, he made his own characteristic contribution to the “new Negro.”

His book The Negro, anticipating anti-colonial conferences organized after the First World War, corrected popular impressions that American blacks were without roots by celebrating the African past. Then Black Reconstruction, written out of Du Bois’s new enthusiasm for Marxism in the 1930’s, recovered the significance of black people in the history of the South. Despite limitations of style, these historical re-evaluations initiated a scholarly revisionism comparable to the redirection of thought in the book Souls of Black Folk.

The Black Flame

Nearing the end of his life, Du Bois published his most comprehensive treatment of America, The Black Flame, a trilogy binding into one narrative an historical account of the years corresponding roughly to his own life and a fictional account of Manuel Mansart. That the plots are meant to interrelate goes without saying. More to the point is the observation that Du Bois’s career, capped by the trilogy, was his most important dialectical demonstration. Seeking to write as truthfully as possible, he became not only a scribe of history but its maker.

[Title Image by Addison N. Scurlock, via Wikimedia Commons]