The Enduring Influence of Ethiopian Philosophy’s Most Enigmatic Texts

Forgeries or masterworks? The truth about the Ḥatäta Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob and its companion treatise has eluded scholars for generations. A new edited volume looks beyond the authorship question, celebrating the philosophical and literary qualities of these texts and their impact on international scholarship.

Sometime early in the seventeenth century, a scholar named Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob (Zera Yacob; ዘርዐ ያዕቆብ in Gǝʿǝz; 1599 – 1692) woke in the cave that served as his home. He sat down at the entrance to the cave and looked out over the landscape that stretched beyond the deep river valley below, contemplating the splendor and magnificence of creation, and the depravity of human affairs that had forced him to flee here. He opened a small book – the psalms of David – and read from it, praising the creator of all he saw, and trying to understand how the goodness of God and his creation was compatible with the evil of human affairs. Decades later, when our philosopher returned to civilization, he wrote his philosophical ideas and produced the work we know today as the Ḥatäta Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob.

Or did he? The Ḥatäta Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob and its companion treatise the Ḥatäta Wäldä Ḥəywät are enigmatic and controversial works. Respectively Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob’s autobiography and a treatise of social ethics by his disciple, they are composed in the Gǝʿǝz language and set in the highlands of Ethiopia during the seventheenth century. Expressed in prose of great power and beauty, they bear witness to pivotal events in Ethiopian history and develop a philosophical system of considerable depth. However, they have also been condemned by some as a forgery, an elaborate mystification successful in deceiving generations of European and Ethiopian scholars.

“The near-exclusive focus on this question over the last century has obscured scholarly interest in the texts’ philosophical and literary qualities.”

In Search of Zär’a Ya‛ǝqob sets the study of these fascinating texts on new ground, presenting a clear account of existing scholarship on these texts and the ways they are being investigated by contemporary philosophers, philologists and historians. The book opens with an extensive introduction by Jonathan Egid about the narrative of the texts, as well as their historical context, before moving on to the seemingly intractable debate over the authorship of the texts.

The various contributions are divided into two sections: history and philosophy.

Beginning the first section are two of the most important recent commentators on the Ḥatätas, Getatchew Haile and Anaïs Wion, who provide opposing views on the origins of the texts in the first two chapters. Ralph Lee then presents some reflections on his recent rendering of the Ḥatätas in English. John Marenbon steers the topics towards the history of philosophy using a selection of mediaeval examples—in particular the historiography of the dispute over the love letters of Abelard and Heloise—a dispute that presents some striking parallels with the Ḥatätas, while Neelam Srivastava focuses her essay on a troubled episode in the reception history of the Ḥatäta Zär’a Ya‛ǝqob, discussing the influence of racial theories on the (in)famous refutation of an Ethiopian authorship by the Italian scholar Carlo Conti Rossini. Taking up the “exceptionality” of the Ḥatätas in the context of seventeenth-century Ethiopia, Eyasu Berento seeks to demonstrate deep continuities with earlier forms of thought from the Gǝʿǝz tradition.

The philosophy section begins with Peter Adamson, who situates the Ḥatätas in particular and Ethiopian philosophy in general within the broader regional context of Eastern Orthodox thought, drawing fascinating parallels with medieval Islamic philosophy. Developing ideas initially proposed in his Amharic-language analysis Ethiopian Philosophy: An Analysis of Ḥatäta Zär’a Ya‛ǝqob and Wäldä Həywat, Brooh Asmare argues that scholars have failed to consider the significance of Ethiopian cultural history in understanding the Ḥatätas, not least in relation to what he takes to be its central theme: asceticism. Binyam Mekonnen offers another perspective on the Ḥatätas from within the tradition of Gǝʿǝz literature, focusing his contribution on the fifteenth-century heretical sect known as the Däqiqä Estifanos, and Fasil Merawi considers the relevance of the Ḥatätas to contemporary African philosophy, making the provocative argument that not only are the Ḥatätas forgeries, but even if they were not, they could not serve as a foundation for Ethiopian philosophy. Anke Graness examines the place of the Ḥatätas in the broad sweep of the historiography of philosophy, with an eye to issues around canonization in African philosophy and in other philosophical traditions globally. In the final essay, Henry Straughan and Michael O’Connor return us to the core philosophical topics raised by the Ḥatätas themselves in epistemology, ethics and the philosophy of religion.

While the authorship question is addressed in the volume, it is not the sole locus of discussion. The near-exclusive focus on this question over the last century has obscured scholarly interest in the texts’ philosophical and literary qualities. Accordingly, In Search of Zär’a Ya‛ǝqob begins to fill this gap by exploring the implications of these texts for the global history of philosophy and transnational intellectual history of the seventeenth century.

“Persevering through these delays and setbacks was not always easy.”

This volume gathers contributions of scholars from four continents on various aspects of the Ḥatätas. The conference which initiated the project took place in Oxford under the auspices of Philiminality Oxford, and was delayed first by the COVID-19 pandemic and then again by the war in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. The conference regrettably came too late to be attended by Getatchew Haile, who had been due to speak via video link but sadly passed away in 2021. Persevering through these delays and setbacks was not always easy. In the end, however, we were able to go ahead with an in-person conference in 2022, eventually yielding the first truly international collection of perspectives on these fascinating works.

Did you know? The Hatata Inquiries (De Gruyter, 2023) presents both texts in an accessible English translation.

Especially important for this was the arrival of five Ethiopian scholars, including one of the editors of this volume, Fasil Merawi, and colleagues from universities across the country. Their contributions to the volume offer a wide and often conflicting array of perspectives on the philosophy and history of the Ḥatätas, demonstrating not only the liveliness of the debates in contemporary Ethiopia and the global diversity of opinion on the authorship question, but the importance of international and transcontinental collaboration in philosophical and historical research more generally. For too long, the discussion of the texts proceeded independently in Anglo-European and Ethiopian intellectual circles, hindering the study of the Ḥatätas in both. It seems to the editors of this volume that bridging this gap is a prerequisite for serious future study of these texts.

This is one reason why it was so important for us to seek to publish this book in open access, making it accessible to as many scholars as possible in Ethiopia and beyond. So please do enjoy the book and share it widely!

As Jonathan Egid concludes in the volume’s introduction:

Whoever the author, the Ḥatäta is a most remarkable document: a profound work of philosophy and an anguished reflection on political and religious conflict, an account of spiritual struggle and a compelling narrative of a life in thought. Regardless of the author, and regardless of the broader cultural significance of the work, it is, like all true classics of philosophy, a text that demands careful study and repays that effort with beauty and insight. These insights have too often been obscured by the controversies surrounding the text, inhibiting any real discussion of its intrinsic significance. This book is an attempt to initiate such a discussion anew.

Learn more in this related title from De Gruyter

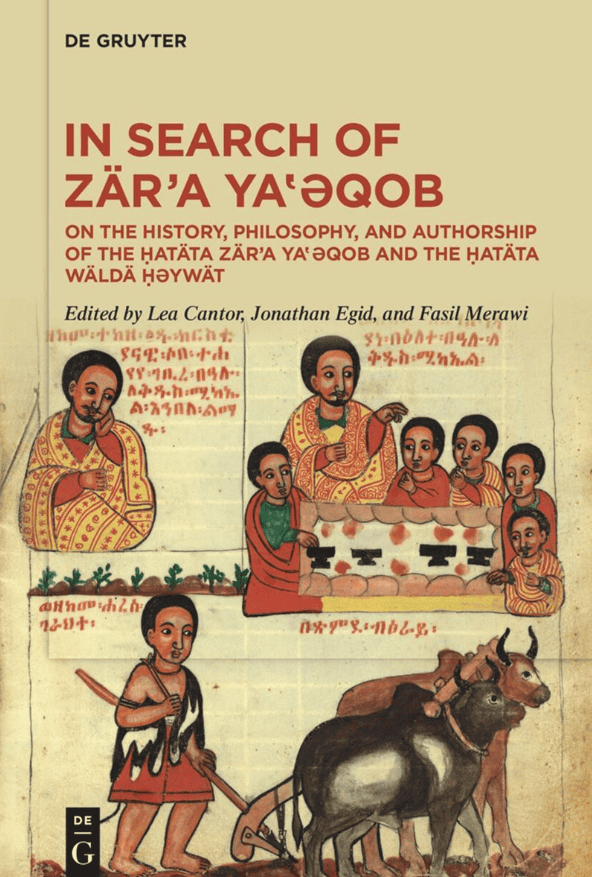

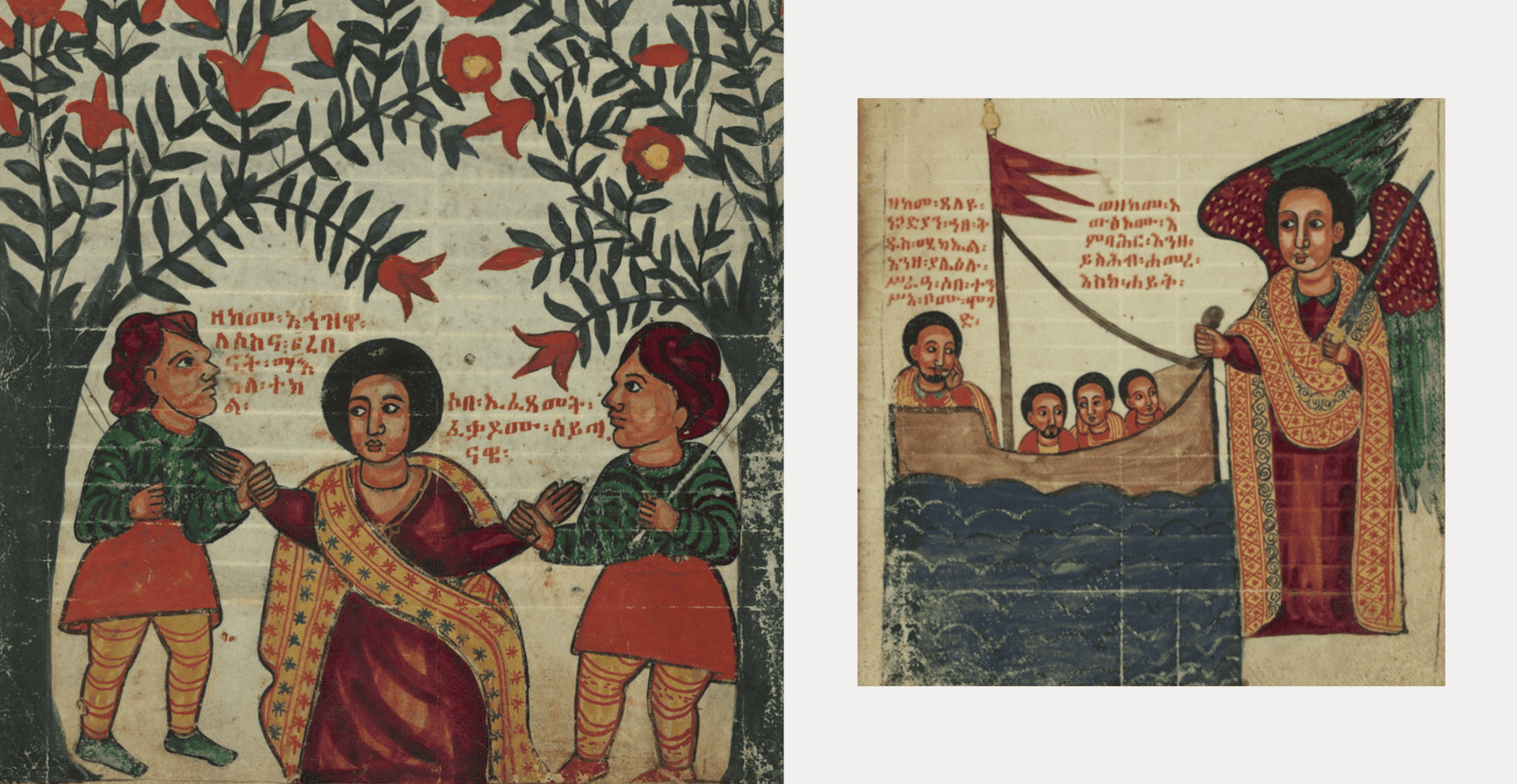

[All images taken from 17th century Ethiopian Manuscript: The Miracles of the Archangel Michael/Public Domain Review.]