How Kraftwerk Invented Electronic Music

When Kraftwerk released their album “Autobahn” in 1974, little did the band foresee that their very German brand of elektronische Volksmusik would change the course of pop music forever: their music of the future, made by machines, has become our reality today.

Kraftwerk released its album Autobahn in November 1974. Although its title track is today considered to be the most iconic song in German popular music, the album largely met with disinterest in Germany at the time.

While the B-side featured atmospheric instrumentals in a vein similar to the band’s three previous, more experimental, albums – which were the result of the creative direction of Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider – the entire A-side of Autobahn was taken up by the stunning title track, which ran to nearly 23 minutes. An edited three-minute version of the track entered the US Billboard charts and also became a top 20 hit in the UK in 1975.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Default. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

The song, or rather the musical composition, differed greatly from the previous work of Kraftwerk and their Krautrock contemporaries. It emulated a car journey on the Autobahn and set out to mimic the boredom and monotony of driving through its repetitive rhythm and the recurrent refrain ‘Wir fahr’n, fahr’n, fahr’n auf der Autobahn’ [We drive, drive, drive on the motorway]. This emulation was also enhanced by synthesized tooting horns, the simulated Doppler shift of passing cars and the mise-en-abyme of Autobahn being played on a car radio.

“Vor uns liegt ein weites Tal / Die Sonne scheint mit Glitzerstrahl / Die Fahrbahn ist ein graues Band / Weiße Streifen, grüner Rand”

Industrielle Volksmusik

Ralf Hütter repeatedly described Kraftwerk’s music as industrielle Volksmusik, a deliberate expression that resonates deeply in German culture. The phrase’s literal translation as industrial folk music does not do justice to the ambiguities in the German language. The use of ‘industrielle’ is not a stylistic reference to the noisy (anti‐)music developed by Throbbing Gristle. Instead, it refers to the highly-industrialized Rhein-Ruhr region in which Hütter and Schneider both grew up. In other words, it refers to a modern civilization based on technology, manufacturing and the use of machines. This further implies an association with the modernist notion that noise can be beautiful and hence typifies a contemporary musical aesthetic.

Likewise, what Hütter calls Volksmusik is not the folk music British or American audiences might expect. On the contrary, the term refers to Kraftwerk’s modern take on regional musical traditions in Germany and therefore suggests an originality which distinguishes Kraftwerk’s machine music from the dominant Anglo-American cultural influences which pervaded post-war Germany. Furthermore, the term refers to the democratic nature of popular music, namely in the sense that it is music made both for and by the people. Overall, then, the label industrielle Volksmusik captures the band’s aim to challenge the dominance of Anglo-American rock music, whilst constructing a new, legitimate national identity in the wake of the atrocities committed by the Nazis.

The music incorporates mechanical noise and was largely, although not yet entirely, produced using electronic music technology in favour of traditional instrumentation. The song and its German lyrics are deceptively simple, appealing even to children, yet they also constitute the central piece of a complex Gesamtkunstwerk because of their connections with the music and cover art. The track updates avant-garde ideas and techniques (e.g. Russolo’s futurism) to create a contemporary, specifically German aesthetic that had a major impact on the development of popular music across the globe.

Radio-Aktivität (1975)

The ambiguous title of Kraftwerk’s next album caused confusion. Radio-Aktivität was largely deemed to be a paean to nuclear energy, which was a subject of considerable political protest at the time by the emerging ecological movement. In later remixes, Kraftwerk dispelled all doubts about their position on nuclear energy by changing the lyrics of the title track to ‘stop radioactivity’. Yet, at the time of release, Kraftwerk agreed to have promotional shots taken which showed the band members wearing white lab coats in a Dutch nuclear power plant. This move further contributed to the common view that Radio-Aktivität is about the theme of nuclear energy, though it was in fact inspired by the band’s visit to the USA during their extended tour in 1975 to promote Autobahn.

Whilst travelling in the USA, Hütter and Schneider were impressed by the large network of radio stations, and also discovered that Billboard magazine featured the most played singles under the heading Radio Activity. ‘Suddenly’, band member Wolfgang Flür remembers, “there was a theme in the air, the activity of radio stations, and the title of Radioactivity Is In The Air For You And Me was born. All we needed was the music to go with it. The ambiguity of the theme didn’t come until later”.

The ambiguity mirrored in the album’s title reflects the core concept of Radio-Aktivität. Like Autobahn before, Emil Schult provided striking artwork which shows the front and back sides of an outdated radio receiver on the front and back covers of the album, respectively. Not only did this suggest a tension between obsolete technology and the avant-garde music heard on the record, but clearly referenced the Nazi past through the image’s strong resemblance to a DKE 38 model Volksempfänger, which was used to receive Nazi propaganda in German homes.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Default. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

The lyrics are neutral in tone, not least because there is no explicit mention of nuclear power plants. Only the last line in German appears to relate to nuclear energy, though its meaning, again, is neither strongly affirmative, nor critical. Given that Hütter and Schneider admired Andy Warhol as a model artist, their highly ambiguous writing could well have been derived from him.

Radio-Aktivität marked an important stage in the development of the band as they pursued full artistic control over their output. Not only was Radio-Aktivität the first album conceived entirely with electronic instruments, but its production was handled entirely by Hütter and Schneider for the first time. The record was also the first to feature the classic Kraftwerk line-up by adding Wolfgang Flür and Karl Bartos and, having signed with EMI, it was the first release on their vanity label Kling Klang Schallplatten. This onomatopoeic name was also given to their new artistic headquarters in Düsseldorf, the Kling Klang Studio, which was located until 2008 in an anonymous building on 16, Mintropstrasse, near the main Düsseldorf railway station.

Trans Europa Express (1977)

With Trans Europa Express, Kraftwerk moved from experimental sounds to formal structures and melodies. The album about train travel through Europe re-visited the theme of transportation in Autobahn, but expanded it from a German national icon to an idea of European integration as expressed in a transnational railway system. The Trans Europ Express (TEE) network was in operation from the late 1950s until the early 1990s. At its height, it connected 130 cities across western Europe with regular services every two hours. As such, the system rep- resented a modern, if expensive, lifestyle as the trains only offered first-class fares.

“The railway is an ambivalent symbol in the context of German history, given the Nazi’s use of the railway system to transport deportees to death camps in the East.”

The railway was a strong symbol of modernization due to its role as a driving force of industrialization. Historically, railway technology can be seen, along with the car, as another key German technology. As the Autobahn, however, the railway is an ambivalent symbol in the context of German history, given the Nazi’s use of the railway system to transport deportees to death camps in the East.

Furthermore, it is this past which drove the Federal Republic to proactively develop greater political integration with Europe and create a shared European cultural identity. The latter impulse clearly underpins Kraftwerk’s artistic efforts. Given that France and Germany were the early driving forces of European integration under Adenauer and France’s first post-war president, de Gaulle, it is fitting that the lyrics of the title song sketch a journey on the TEE from Paris via Vienna to Düsseldorf, a route often travelled by members of Kraftwerk (though, obviously, without the detour via Vienna).

Traditionalist Imagery and Futuristic Music

The album’s artwork offers a prime example of Kraftwerk’s guiding retro-futurist aesthetic in practice. This concept aims to fuse utopian notions with nostalgic images to create an aesthetic tension that confronts the present with un- redeemed past promises of a better future.

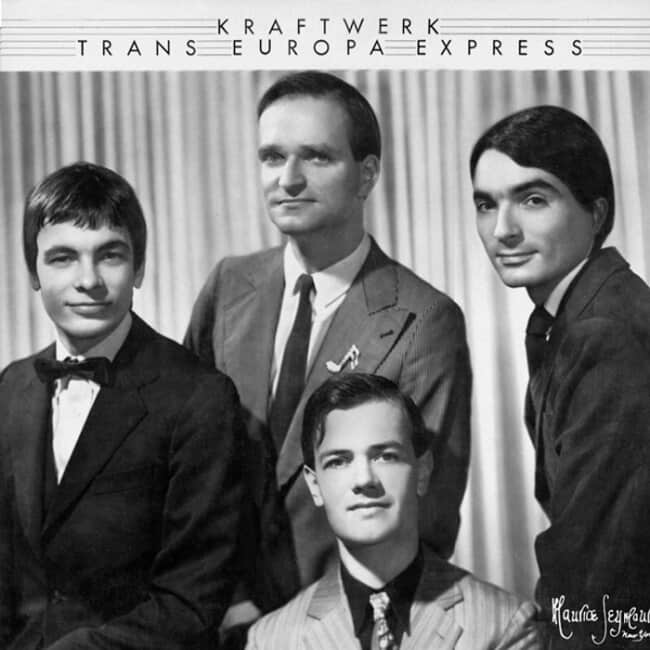

Following what seems to be a conventional design approach, the cover features a photo of the four band members. The album was released at the apex of the punk explosion, yet the image conveyed was totally at odds with the spirit of the times. The band portrait was taken by the American celebrity photographer(s) Maurice Seymour, and shows the band members dressed conservatively in suit and ties in the style of a group portrait typical of the 1930s or 1940s. Only a Rhinestone brooch in the form of a musical note worn by Schneider hints at the irony involved in staging the musicians in this way.

Such out-of-date and traditionalist imagery stands in marked contrast to the decidedly futuristic music on Trans Europa Express, which was released at the very moment when ‘no future’ provided the call to arms for England’s punk movement. Moreover, whilst British punk was denouncing royalty and the British establishment, Kraftwerk was singing the praises of an endless Europe in the opening track of the album. Against the gritty urban realism of punk, Trans Europa Express paints a rather romantic and often melancholic picture of the European continent, grounded in the natural beauty of its landscape (although also taking care not to fall prey to clichés).

“Flüsse, Berge, Wälder / Europa endlos / Wirklichkeit und Postkarten-Bilder / Europa endlos / Eleganz und Dekadenz / Europa endlos”

With Schaufensterpuppen and Spiegelsaal, Trans Europa Express features two songs whose lyrics follow an unusually expansive, narrative structure, focusing in both cases on the theme of identity loss and objectification. Schaufensterpuppen and Spiegelsaal prefigured the key conceptual theme – the man-machine – which Kraftwerk explored on the follow-up album in two important ways. Firstly, the songs responded to the accusation that the band performed like mannequins on stage. Secondly, they critically examined the (psychological) pitfalls of stardom.

The future of electronic dance music

Spiegelsaal can be read on various levels, not least from a cultural anthropological perspective as a rite of passage according to the three-stage model proposed by Arnold van Gennep (i.e. separation, liminality, incorporation). In a more obvious sense, the lyrics can be seen as a warning about what happens to pop stars (such as David Bowie, who is evidently referred to in the chorus): fame condemns them to live their lives in the looking glass of public scrutiny, which forces them to change themselves and live a public persona. With hindsight, it is clear that Hütter and Schneider took heed of the transformative, problematic aspects of fame, as exemplified by Bowie, by retreating into privacy, essentially refusing to discuss their work and shielding their private lives.

The album’s title track, which is often regarded as one of Kraftwerk’s masterpieces, proved to be of crucial importance for the development of electronic music. It is actually a suite of three tracks which merge smoothly into one another. The techno pop track Trans Europa Express is followed by the instrumental Metall auf Metall, which features ferocious metal percussion, and is concluded with the short outro Abzug (essentially the sound of a train departing). The 13-minute Trans Europa Express suite is based on relentless repetition, propelling the listener onward, emulating the velocity of train travel by marrying it with the constant forward flow of beat-driven music. Extending the approach heard in Autobahn, this musical simulation of train travel exemplifies Kraftwerk’s artistic aim to translate the industrial sounds of pulsating noise and metal clanging into a modern machine-based music.

Harking back to the attempts of Dadaists and futurists of the 1920s and 1930s to incorporate industrial modernity into art, Kraftwerk’s techno pop paved the way for the future of electronic dance music.

Key Conceptual work: Die Mensch-Maschine (1978)

Die Mensch-Maschine is Kraftwerk’s key conceptual work. In stark contrast to the retro style of photography in Trans Europa Express, Kraftwerk now appeared on their latest album cover as a uniform group of pale mannequins in red shirts and black ties. The futurist styling of the album is also coupled with the bold graphic art of Karl Klefisch, whose design and typography visibly reference the work of the Soviet avant-garde artist El Lissitzky, which strongly influenced suprematism, constructivism and the German Bauhaus movement.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Default. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

Mensch-Maschine is central to Kraftwerk’s Gesamtkunstwerk in that it constructed their corporate identity, although its music also proved vital to their career. After all, the album contains their only UK number one hit single Das Modell. The song, written in a typical pop style and featuring the only female protagonist in their oeuvre, was a nod to Düsseldorf’s status as Germany’s leading fashion capital at the time. However, the themes of its lyrics – commerce, sex, drinking and dancing at a chic nightclub – are rather at odds with the highly post-human, futuristic orientation of the album.

The romantic Neonlicht, much loved and often covered because of its lilting melody, is likewise a song about Düsseldorf, paying tribute to the many colourful neon signs that advertise shops, hotels and bars in the city. Indeed, many examples of neon advertisements, though mostly for sex shops and seedy bars, can be found to this day in the area where the Kling Klang studio was originally located.

Metropolis pays homage to the masterpiece of German Expressionist cinema by Fritz Lang. His film Metropolis, one of the first science-fiction movies, featured a robot and exerted a major influence on Kraftwerk. Indeed, posters promoting their 1975 USA tour already showed an artist’s impression of the futuristic city of Metropolis as envisaged in Lang’s film and announced Kraftwerk (in German) as Die Mensch-Maschine to their American audience.

Robots and Man-Machines

Accordingly, the band appropriated the image of the robot to act as the avatar for their concept of the man-machine. To promote the album, robot mannequins were built of each member in the band and, to this day, these likenesses of the band members appear on stage to accompany their theme tune, Die Roboter. The robot mannequins embody a fitting metaphor for the work ethos of the band. In one of his various attempts to construct an artistic identity distinct from the band’s rock contemporaries, Hütter claimed, “We are not scientists nor musicians. We are workers.” Indeed, Kraftwerk’s highly conceptual electronic music project represented a conscious, deliberately constructed aesthetic offence to traditional rock values where a sense of unbuttoned maleness, of hair and heart and emotive authenticity was paramount.

“The machines are part of us and we are part of the machines.”

As Hütter has repeatedly stressed, he sees the band as the human vehicle for their man-machine concept. Accordingly, a robotic voice has for years announced the band as Die Mensch-Maschine Kraftwerk before the beginning of their concert performances. On the subject of man and machine and music, Hütter explained in 1978: “The machines are part of us and we are part of the machines. They play with us and we play with them. We are brothers. They are not our slaves. We work together, helping each other to create.”

Hybrid Beings, Ambivalent Feelings

From a performance point of view, the occasional mistakes that the band make during concerts underline the fact that humans, not machines, are making the music. Similarly, close examination of the robot and man-machine concepts reveals a characteristic degree of ambivalence. Though Kraftwerk’s overall faith in the positive capabilities of technology remains unbroken, they do not communicate this naïvely. In this respect, Kraftwerk connects their artistic project to the cultural-historical tradition of the man-machine.

From Julien Offray de La Mettrie’s treatise L’homme machine (1747) and the first mechanical automatons in the eighteenth century, to the depiction of uncanny characters in nineteenth-century literature (such as Olimpia in E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Der Sandmann from 1817 or Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein from 1818), to the female robot Futura in Lang’s Metropolis, man-machines are hybrid beings that inspire in us ambivalent feelings of fear and hope with regard to technology.

Kraftwerk’s characteristic play with ambiguity can be detected in the paramilitaristic look the band has on the Mensch-Maschine cover. At first glance, it evokes unwelcome associations for many Germans, not least because the colour scheme matches the colours of the Nazi flag. In this light, the quartet of robots could be seen as a reminder of the willing executioners, upon which German fascism relied to obediently follow orders without asking questions. Thus, in yet another retro-futuristic turning of the tables, the band managed to fuse a reference to the German past with our technologically-governed future.

Computerwelt (1981)

With Computerwelt, the band attained their musical peak and completed a seven-year series of ground-breaking albums. Three years in the making, its release went on sale shortly before the first personal computers (PCs) came on the market. IBM launched the rather expensive 5150 in August 1981, Commodore launched the more affordable Commodore 64 – the first true home computer – in August 1982, and Apple launched the first Macintosh computer in January 1984 – all within two and a half years of the release of Computerwelt.

On their prophetic album, according to Buckley, Kraftwerk ‘do not predict a robotised, sci-fi future. However, they do predict, with complete accuracy, that our modern-day lives will be revolutionised’ by computer technology.

“Automat und Telespiel / Leiten heut’ die Zukunft ein / Computer für den Kleinbetrieb / Computer für das Eigenheim”

Ironically, the studio production of the album was analogue and did not yet involve any computer technology, underlining the visionary power of the album. Computerwelt is less retro than any other Kraftwerk album – and consequently their most futuristic work. Schneider’s interest in gadgets and the ubiquity of microchip technology throughout everyday life at the time is reflected in the playful Taschenrechner. Computerliebe with its seductive melody was yet another track of visionary quality given the manifold opportunities the internet now provides via social networking and matchmaking sites, whether for romantic or erotic ends.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Default. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

However, this song captures a degree of sadness and alienation by envisaging a scenario of personal isolation in a future saturated with technology and lacking in purpose and emotional connection. The pronounced ambivalence at the heart of this vision of the advent of our present-day computer world can hardly be overlooked. And in a way, this prediction was correct considering that increased digital communication has been seen to foster the dissolution of established traditional social interactions and communities.

From today’s perspective, in the context of revelations surrounding British and US government surveillance operations, the dystopian mood of Computerwelt turns out to be chillingly prescient. After all, Kraftwerk not only correctly predicted the triumph of computer technology, they also envisaged the near-totalitarian control it would take over our lives and its immense potential to exert power over society.

Surveillance and critique

Arguably, such wariness towards instruments of social control can be attributed to the German experience of both the totalitarian regime under Hitler and the dictatorial system of the GDR. The disciplinarian reach of the Nazi apparatus and the East German secret police (Stasi) were strong enough already, but, as Kraftwerk perhaps sensed, the introduction of a computerized means of surveillance would give authorities even stronger powers to police the population.

In the late 1970s, the German Federal Crime Agency introduced the new technique of Rasterfahndung in order to identify the location of wanted terrorists in the Baader-Meinhof group. The public hysteria about terrorism at the time clearly abetted this innovative way of computer- aided database analysis. Its success was rather limited but raised considerable unease amongst many due to the dystopian prospect of government agencies collecting and analysing the data of innocent citizens on a large scale. Accordingly, alongside other crime agencies and financial institutions, the Bundeskriminalamt is referenced by its acronym BKA on Computerwelt.

“Interpol und Deutsche Bank / FBI und Scotland Yard / Finanzamt und das BKA / Haben unsre Daten da”

Anticipating big data

By replacing words with numbers (or strictly speaking: numerals), Kraftwerk arguably anticipated (at least in part) that a merciless flow of numeric data would increasingly replace traditional communication and cultural exchange based on words and literacy. With Computerwelt, Kraftwerk not only displayed a remarkable degree of foresight in predicting a world based on computer technology, but, crucially, they backed this up with an uncompromising and serene musical vision of the emerging sound of the future.

Compared to previous records, the now truly futuristic sound of Computerwelt was markedly brighter, cleaner and more clinical. In line with their self-styled image as music workers, audio engineers and sound researchers, Hütter explained to an interviewer: “We aim to create a total sound, not to make music in the traditional sense with complex harmony. A minimalistic approach is more important for us. We spend a month on the sound and five minutes on the chord changes.”

From Düsseldorf to the Bronx

This painstaking work produced truly ground-breaking music, the repercussions and resonances of which would also be heard across the Atlantic. The centrepiece of the album in this respect was Nummern. The relentless drum pattern, written by Bartos, made this pivotal track more typical of techno than pop. The beat pattern from Nummern and the melody from Trans Europa Express formed the sampled backbone of Planet Rock by Afrika Bambaataa and Soulsonic Force in 1982. From the black ghettos of New York, this song spawned the electro genre and was striking evidence of the keen reception the machine music from Düsseldorf received amongst black communities in the USA.

Kraftwerk’s music clearly provided a crucial contribution to the development of electronic dance music styles such as house and techno. Particularly in Afro-futurist works, Kraftwerk’s retro-futurist aesthetic offered unexpected synergies with artists like the Detroit production duo Drexciya or the Underground Resistance collective, with the latter paying emphatic homage to the music from Düsseldorf later on with the track Afrogermanic from 1998.

[Cover Image by Magdalena Blaszczuk]