What the Graffiti of Ancient Pompeii Teach Us About Our Modern Selves

Writing “I was here” is one of the most basic forms of self-expression. With a history that goes back several thousand years, graffiti-writing teaches us a great deal about our own habits of self-display.

Graffiti are part of the contemporary urban fabric; they colourfully cover buildings and trains, remain as traces left behind by visitors at tourist sites, or reveal the names of lovers at romantic spots. As such, graffiti can be perceived both as acts of vandalism or occupation as well as a means of expression or form of ornamentation. Oscillating between art and misdemeanour, they are officially allowed only in areas specifically provided for this purpose, often as parts of social projects intended to enliven or bring colour to certain buildings or quarters, such as segments of the Berlin Wall, or the “Freiraumgallerie” in the former East German city of Halle.

In the cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, visitors can create virtual graffiti via the Autography App instead of writing on the actual walls. Here, the tourists’ desire to leave their mark is taken for granted, but, instead of a prohibition – which might provoke the graffiti-inclined even more –, the city has simply shifted the space to be inscribed from the physical surface to the internet.

The history of Tagging

“Tagging”, or leaving your own name on spots you have passed or visited, can be observed in all present and past societies that use script. Even though the form of tags – their script, images, naming systems, etc. – has varied throughout history, the practice of tagging seems to be deeply rooted in human nature. “So-and-so was here” can announce a personal connection to a place, document an emotionally important situation, display a visit, or be nothing more than a doodle – but it is always a form of self-commemoration and self-display.

“The practice of tagging seems to be deeply rooted in human nature.”

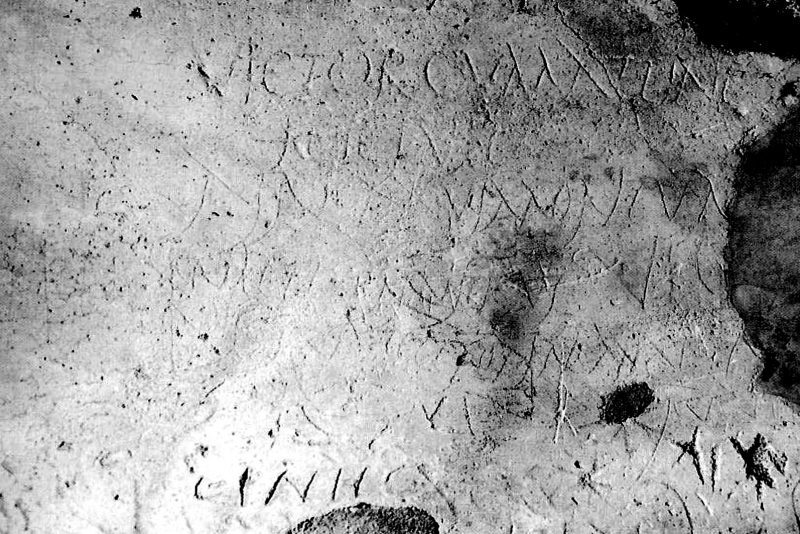

In view of the fact that graffiti is today illegal in most cities or, at best, banned to designated areas, it is easy overlook the long history of leaving marks on walls and the possibly different perception of this ‘habit’ in other eras and cultures. Excavations in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome have revealed a rich corpus of graffiti scratched into the floors and walls of public and private buildings, and incised in everyday objects like ceramic vessels. But one thing remains constant across time and place: the majority of these inscriptions consist of names, most likely those of the writers and frequently combined with the phrase “… was here”.

Displaying a Slice of Life

Over 5000 wall graffiti have been found in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii alone. These contain mostly name tags (37%), but also include greetings, messages, obscenities, quotes from famous literary works, drawings of animals and gladiators, numbers, dates, and prices. In short, they reflect everyday life: the greetings of a certain Tyrannus (possibly a slave) to Cursor (his friend?), the multiple signatures of a certain Rufus in the garden of the large Casa del Menandro, gossip about the girl Romula who “had 1000 men”, a message from Severus to Successus claiming the girl Iris for himself, numbers documenting business transactions in shops, a customer complaining about too much water mixed into wine, the gladiator Oceanus winning against his opponent Aracintus.

In the theatre of Pompeii, where a large number of graffiti are concentrated, graffiti often imitate one another. This probably is the same phenomenon that we can observe in modern touristic hotspots: graffiti accumulate in heavily trafficked places, with one graffito inspiring others. This, too, reflects a typical behavioral pattern: people do what other people do; a wall is much more likely to be tagged when there are already tags present to reduce the possible inhibition associated with marking public property.

The walls of Pompeii seem to have been used for daily interactions, and reveal little stories about neighbourhood characters and life in the town. Such local anecdotes might not be of interest for those studying the main events and vicissitudes of history, but they do help us understand how people communicated publicly about private things, left marks on spots they passed, and displayed personal connections such as friendship and love, but also anger and rivalry, on the wall. In the brothel of Pompeii, dozens of (male) visitors even left commemorations of their visits, visible to all following clients.

An Ancient form of Social Media?

In this respect, ancient graffiti were not that different from modern social media as a form of self-display and self-commemoration. They differ, however, despite the homonymy, from modern (sprayed) graffiti in important ways. They were, for example, smaller and visually more discreet, so that they must have been rather difficult to spot if you did not know where to look or what to look for. The fact that the preponderance of Pompeian graffiti was made inside houses calls into question our modern assumption – shaped by contemporary graffiti – of graffiti-writing as an illegal practice.

[mailpoet_form id=”2″]

As with modern social media, Pompeian graffiti were also subject to phases and trends: gladiators and ships belonged to the favourite motifs for sketches, and writing names in the shape of a ship soon caught on as well; the same lines from popular literature were written on the walls over and over again, and greetings mostly repeat the same, fixed phrase that we also find in Roman letters. When a certain Aemilius began to write his name backwards, two other men, Curvius and Sabinus, took up the practice as well, until all three of them were messaging each other in this manner on the walls of one particular house. The word “Menedemerumenos”, whose meaning we do not know, also came into fashion at some point and spread all over town, perhaps as a kind of riddle or game.

“Meant as an individual self-display, the graffiti clearly reveal patterns of human behavior.”

Although these marks, messages, and stories incised into Pompeian buildings are personal expressions, they are, at the same time, often formulaic to the point of redundancy. Meant as an individual self-display, the graffiti clearly reveal patterns of human behaviour in general as well as local writing fashions. The same tendency can be observed in modern social media, where trends affect content, design, and marketing strategies; social media is dominated by the latest meals and travels people share online with the whole world, leaving the impression that our society consists of happy, wealthy people who spend their life travelling to beautiful destinations and eating beautifully arranged food.

The message of mass

I am myself a blogger; I use Facebook and Twitter to promote my own research, and I have just recently discovered Instagram for private purposes. I am, however, still compelled to wonder why people would be interested in the least at looking at my breakfast table. Am I worth being recognized and remembered? This question is closely connected to the question of how authentic we are by simply following given patterns and by being fully aware of the audience we have. Is it still us we represent online, or is it merely an image or fictional character which we create of ourselves and which is tailored to social expectations and current fashions? With hundreds of names scratched into the walls of Pompeii, each one of them is part of a large, uniform mass in the same way that I am just one of many millions of people dedicated to social media, however unique I try – or imagine myself – to be.

“Is it still us we represent online, or is it merely a fictional character which we create of ourselves and which is tailored to social expectations and current fashions?”

What does the mass of often redundant, formulaic graffiti from Pompeii tell us? Amongst other things, it tells us something about how graffiti was seen by Roman society at large. Graffiti were mostly placed in highly frequented spaces, including the central rooms of private residences. This suggests that graffiti were, if not welcomed, at least tolerated, probably in part because they were not visually disturbing. Being scratched into the wall-plaster (and therefore also into the frescoes which covered the walls!), graffiti give us a new understanding of the perception of space and decoration in antiquity: it reminds us that that which we call art and today treat as sacrosanct was, in antiquity, a functional object, a surface to be used for writing.

Carved Memory

Pompeian graffiti not only quoted literary texts and used popular phrases, but also imitated parts of their surroundings, such as nearby buildings or parts of wall-paintings; sometimes they employed wall-paintings as a visual framework to highlight the inscriptions, and they took delight in playing with their audience in the same way that children like to address their readers: “whoever reads this is stupid”. A closer study of the writers and addressees of the Pompeian graffiti also reveals that women are highly underrepresented as writers in this genre, a fact that might point to the different levels of literacy in Roman society. Only in erotic texts and love messages do women play decisive role; these texts remind us of what one today finds in public toilets or on school tables, but they can also evoke what some people even like to post online.

Sharing one’s private life, thoughts, and opinions online has become normal thanks to social media. This, without doubt, bears many dangers, from companies spying on their employees to teenagers committing suicide because of private videos having gone viral. A careless or injudicious use of social media can negatively affect the rest of one’s life, a danger that should not be underestimated. As a private individual, I therefore try to find the right balance between sharing personal thoughts and experiences, and keeping my privacy. As a professional, however, I appreciate everything people publicly post, whether online or as a graffito on wall, because studying material remains and written traces of (past) societies is a key part of my profession as an archaeologist. These are the very materials which allow us to understand and analyse past and present societies.

However banal ancient graffiti might seem, they are a boon for scholarship, and as an archaeologist and researcher, I am grateful for every kind of memory scratched into the walls of Pompeii: these are rare traces of the lives of average persons. Whether something is worthy of remembrance or not is always a subjective decision, and scholarship has not always had a serious interest in the extant Pompeian graffiti. Regarded as stupid scribbles, the informal inscriptions have, in large part, long been neglected. As scholarly interest began to shift from the history of great men to a reconstruction of daily life in all parts of society, graffiti research has, especially within the past years, experienced a new peak. The phenomenon of graffiti-writing in antiquity does not only make us reflect on modern practices of wall-writing, but also on our habits of self-display, and on the connection between the two.

Complement this story with Konstantinos Kapparis on Prostitution in Ancient Greece and Manuel Knoll on What Plato Would Have Said About Trump and Brexit.

[Title Image by David Soanes via gettyimages]