Uncopyable? Creativity and Judgment in the Age of AI

There’s no such thing as a moral machine – yet. In times of digital offloading, we need to cultivate human creativity once more. After all, real thinking begins where certainty breaks down, not where it is enforced.

The most astonishing experience of working with AI chatbots is the impression that someone is really ‘there,’ as if the answers had truly been thought through. And yet, we know this is not the case, at least not in the way humans think, hesitate, or doubt.

The flow of information itself has changed. What once required time, effort, and often frustration now appears in seconds. Simulated creativity and research that once took months are now available in minutes. While not yet fully trustworthy, it is improving with staggering speed.

From Thinking to Performance

This is the first time that we are dealing with a tool that not only supports thinking, but appears to perform it. It forces a confrontation with a radical question: If machines can think for us, what is our purpose exactly?

When AI outputs become indistinguishable from human reflection, the question of autonomy becomes unavoidable. Autonomy here does not mean freedom from technology, but the ability to form and sustain one’s own judgments without quietly delegating cognition to a system. When that ability weakens, the sense of acting and choosing for oneself begins to fade.

Memorizing information and producing correct answers has only ever been a fraction of the education process. Now, we are forced to go decisively beyond: To learn again how to read slowly, to critically question what sounds convincing, to think creatively beyond given frames, and to articulate and justify our decisions rather than merely accept automated outcomes. These skills are not new, but they have become existential.

“Whether we continue to think for ourselves, or slowly but surely stop noticing when we do not, may be the decisive question of our time.”

Wilhelm von Humboldt described Bildung as the formation of the self through judgment, placing individual responsibility at its center. Under contemporary conditions, however, this process can no longer be sustained by individual effort alone. It depends on institutions and political frameworks that protect time for thinking and resist the pressure of mere efficiency.

What kind of thinkers are being cultivated by our current institutions? This fundamental question recedes into the background when public debate remains focused on optimisation or redistribution. At stake is the fragile space in which creativity and responsibility take shape. Whether we continue to think for ourselves, or slowly stop noticing when we do not, may be the decisive question of our time.

The Problem of Digital Offloading

The core of this challenge lies in how we acquire knowledge. When mental processes are delegated to digital tools, we risk bypassing the essential work of internalizing information. The psychologist Betsy Sparrow described this dynamic as the “Google effect,” observing that individuals who rely on digital retrieval are less likely to store information in their own memory.

While digital retrieval creates a direct link to a fact, true learning constructs a dense network where information is anchored in experience. A society that delegates cognitive tasks to machines does not render human learning obsolete, but instead intensifies the need for a resilient form of judgement that cannot be outsourced to machines.

The Paradox of Delegated Cognition

Orientation, which is the ability to discern what matters, is a question of meaning rather than computation. While machines excel at synthesizing data, they lack the perspective needed to evaluate relevance and consequences once formal rules no longer sufficient.

The paradox of delegation lies here: When algorithmic outputs are treated as benchmarks rather than aids, deviation is reclassified as error. In such environments, judgment gives way to compliance, and the space in which genuine orientation and creativity can emerge begins to narrow.

The Human Act of Judgment

Consider the emergency protocols of a nuclear power plant. Under extreme time pressure and contradictory sensor readings, an AI can rapidly simulate possible outcomes. It can compare scenarios, calculate risks, and rank options. But responsibility still rests with a human being, who must interpret what these patterns mean in a concrete situation.

When an engineer decides to shut down a reactor despite immense economic pressure, this is not an act of mathematical optimization. It is a self-assumed obligation to carry the consequences of that decision. Whatever follows will be tied to a name, a career, and a life.

“Only humans can determine the underlying purpose and ethical necessity of an action, and therefore must remain the decisive authority.”

Technology evaluation must remain transparent and traceable. Only then can it sharpen professional intuition rather than replace it. A surgeon, for instance, might use AI-driven diagnostics as a ‘cognitive mirror’ to reflect on their own findings, yet they must remain the primary epistemic authority. While AI excels at calculating probabilities, only humans can determine the underlying purpose and ethical necessity of an action, and therefore must remain the decisive authority.

AI has no body, no lived experience, and no biography that can be altered by failure. It cannot personally lose trust, reputation, or sleep. In terms of pure processing, this lack of bias and emotion is an advantage. However, it makes the system fundamentally different from a human agent. In situations where something irreversible is at stake, this difference becomes critical. What might seem like a sentimental distinction actually changes how we weigh responsibility and which ethical norms guide our choices.

Recovering Measure through Culture

This capacity for judgment is cultivated not only in high-stakes professional practice but also through cultural experience. In Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens depicts a world governed by discipline rather than care, where crime appears less as moral failure than as a strategy for survival. Evil does not confront Oliver merely as a threat, but as a seductive promise of belonging. Judgment here cannot rely on abstract rules; morality emerges instead as a fragile orientation under severely constrained conditions.

Literature thus functions as an experiential space in which we learn to weigh motives rather than merely classify actions. A similar warning appears in Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo: by regarding himself as an “instrument of God,” Edmond Dantès crosses the boundary between justice and vengeance, sacrificing the limits that make judgment possible in the first place.

Sustaining the Conditions for Thought

What these examples point to is something simple and easily overlooked: Judgment does not sustain itself. It depends on conditions that allow uncertainty to remain. Thinking begins where certainty breaks down, not where it is enforced.

Creativity may be one of humanity’s most powerful capacities, but on its own it has no direction. Without ethical orientation, it easily slips into excess, optimization, or justification. And responsibility cannot rest on individual integrity alone, especially in decision-making environments that accelerate time, dissolve accountability, and quietly invite us to defer to automated authority.

“Cultivating creativity is not merely a personal task, but an institutional one.”

This is why cultivating creativity is not merely a personal task, but an institutional one. It requires environments that protect time for hesitation, allow uncertainty to remain visible, and resist the pressure to collapse decision-making into efficiency. Only under such conditions can creativity flourish and remain oriented toward judgment and responsibility, rather than being reduced to procedure.

The Practice of Thought

How do we cultivate judgment, responsibility, morality, and creativity? These are not achieved solely through the humanities, the reading of books, or the study of role models. What ultimately matters is practice. We learn judgment by acting in the world and by carrying the consequences of our actions.

It is tempting to assume that AI will never produce genuine morality or creativity, even with access to all human knowledge. For morality is not a computational outcome, and creativity is more than just the recombination of data. Both arise from friction with reality, from limits, risk, and inner necessity.

The future remains open. More advanced forms of intelligence may surpass us in thought and expression, and future generations may entrust them with far-reaching decisions, even where human life is at stake.

“Morality isn’t an abstract theory; it is a lived practice—a craft akin to music or the forging of character.”

From today’s perspective, a truly moral and trustworthy machine remains a contradiction. Autonomous systems are oriented toward functional self-preservation rather than moral obligation. In situations of conflict, it is therefore unlikely that such systems would reliably subordinate themselves to human ends or remain perfectly constrained.

One thing is certain: we must sharpen our creativity, judgment, and sense of responsibility today more than ever. Following Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, we are what we do. We become just by acting justly. Morality isn’t an abstract theory; it is a lived practice—a craft akin to music or the forging of character. If we fail to practice, we forfeit not only skill, but the very capacity to act well.

What is true of moral action is true of thinking itself: it endures only insofar as it is practiced. While this alone may not guarantee a livable future, what will is our willingness to cultivate these capacities as an advantage that cannot be copied.

Learn more in this related (German-language) title from De Gruyter Brill

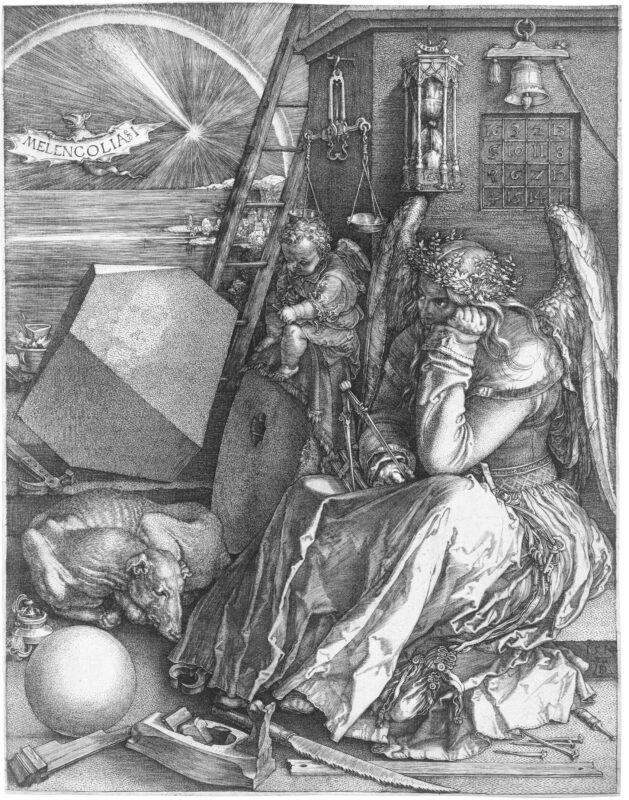

[Title image by EyeEm Mobile GmbH/iStock/Getty Images Plus]