Thesaurus Linguae Latinae: How the World’s Largest Latin Lexicon is brought to Life

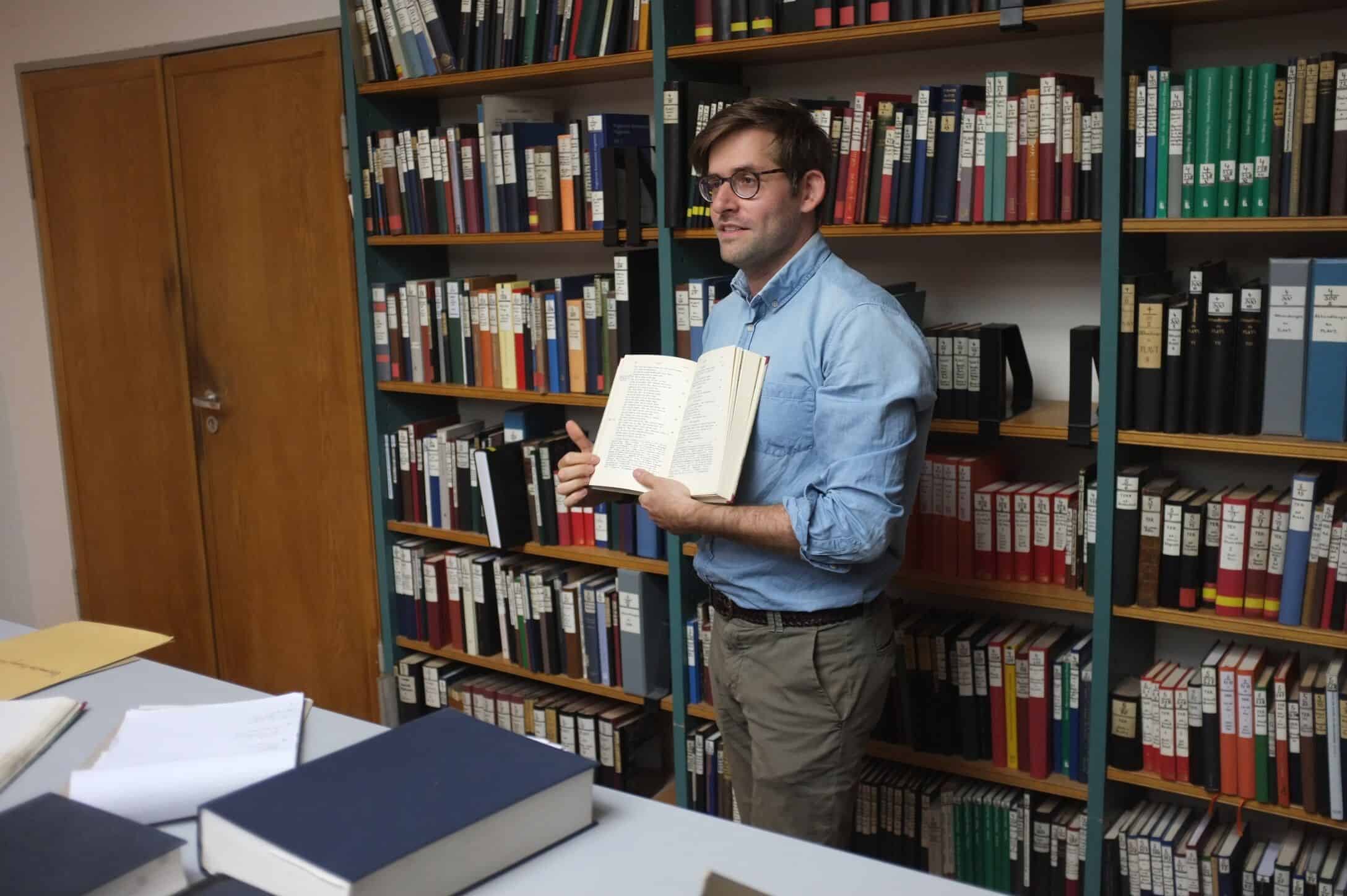

As the world’s largest and most comprehensive Latin dictionary gets a digital makeover, lexicographer Adam Gitner tells us what it’s like to work on a monumental project that generations of scholars have contributed to – but is still a work in progress after 125 years.

In 1882, work first started on the Sagrada Familia, Antonio Gaudi’s art nouveau masterpiece in Barcelona, Spain. The basilica is still under construction today. A few years later in 1892, work commenced on another, less well known but no less ambitious project; the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae (TLL), the most authoritative scholarly dictionary of Latin in the world – also a work in progress.

When finished, the dictionary will not only be the world’s largest Latin lexicon, it will also be the first dictionary to cover all Latin texts from the classical period up to 600 AD. While many dictionaries focus on the most popular use and meaning of a word and quote examples selectively, the TLL aims to document practically all surviving occurrences of every meaning of every Latin word.

Written in Latin, dictionary entries are complex, multi-layered biographies of words which can take years to research and write. The completion date for the Sagrada Familia is said to be 2026 whereas the TLL team predict the dictionary could be done and dusted by 2050. With the size and scale of each project, all bets are off whether either deadline is made.

From ‘Renuo’ to ‘Zythum’

The ‘completeness’ of the dictionary is one the key factors why the work takes so long and also why it’s truly special according to Adam Gitner, one of a small, highly skilled international team of scholars who research and write the entries.

“We cover everything that survives in Latin no matter if it’s a literary work, a theological argument, a cookery book or if it’s a graffito carved into a wall,” he said.

“For me, this is really exciting because you get to see all this non-literary Latin that survives as well. Classics can have a rather stodgy reputation, but I see what we’re doing is radical. For us, a passage from a literary classic like Cicero has equal value for understanding Latin as a graffito from a bar in Pompeii. In fact, the latter is often more interesting and might need comparatively more space to explain.”

At the moment, the team is working on the letters ‘R’ and ‘N’. Originally, ‘N’ was skipped over because it contained some words that would have taken a long time to work on. Thousands of words remain – in fact, all Latin words from ‘renuo’ to ‘zythum’, plus all of ‘Q’ which was passed over in order to begin production of ‘N’.

Despite the lengthy time frame, the editorial team is working to a strict schedule and has been consistently publishing one or two instalments of the dictionary – called a fascicle – every year with 165 currently in print.

Words in Their Millions

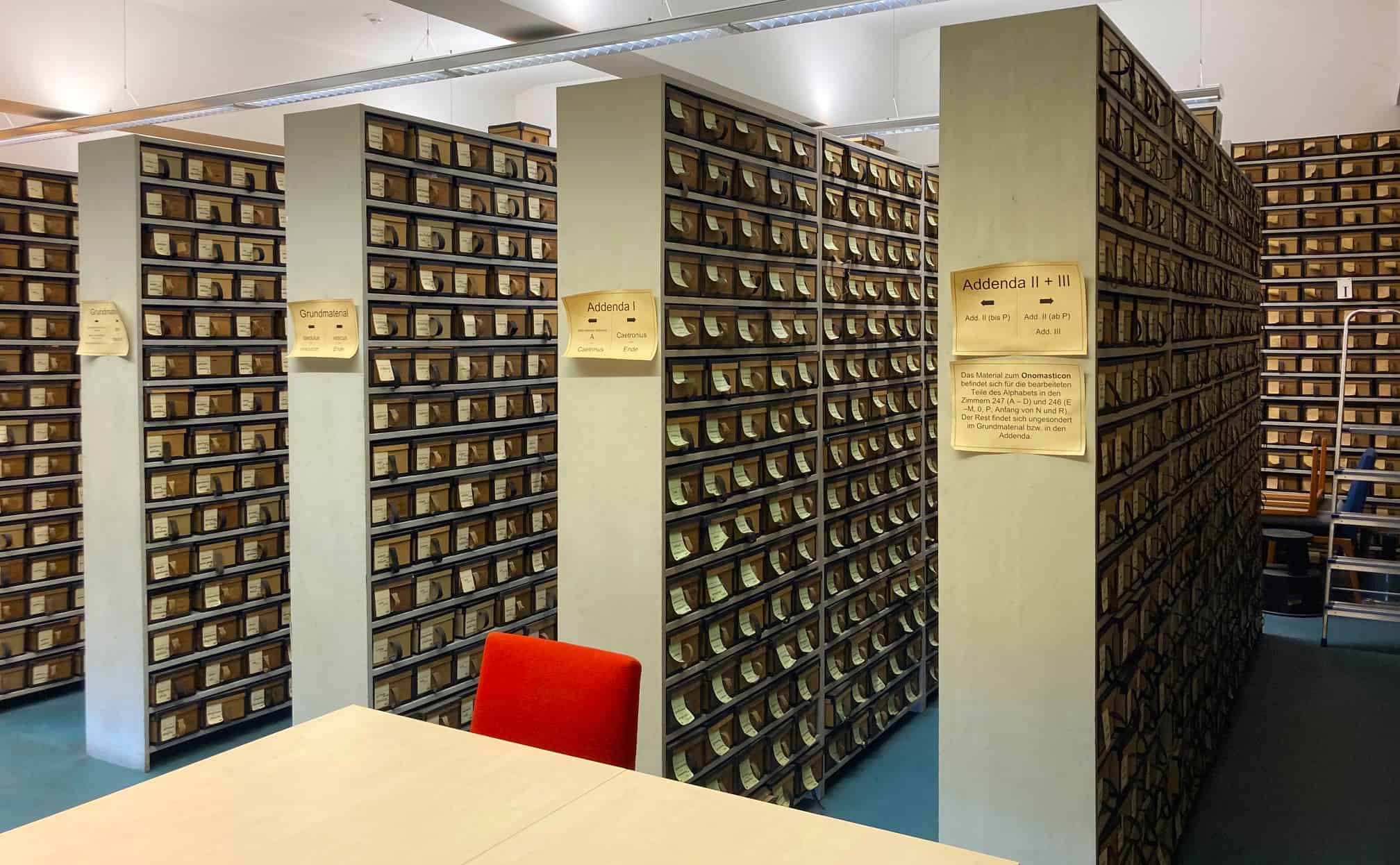

The bedrock of the dictionary is a cavernous archive of 10 million slips stored in the library of the former royal palace in Munich where the TLL is based.

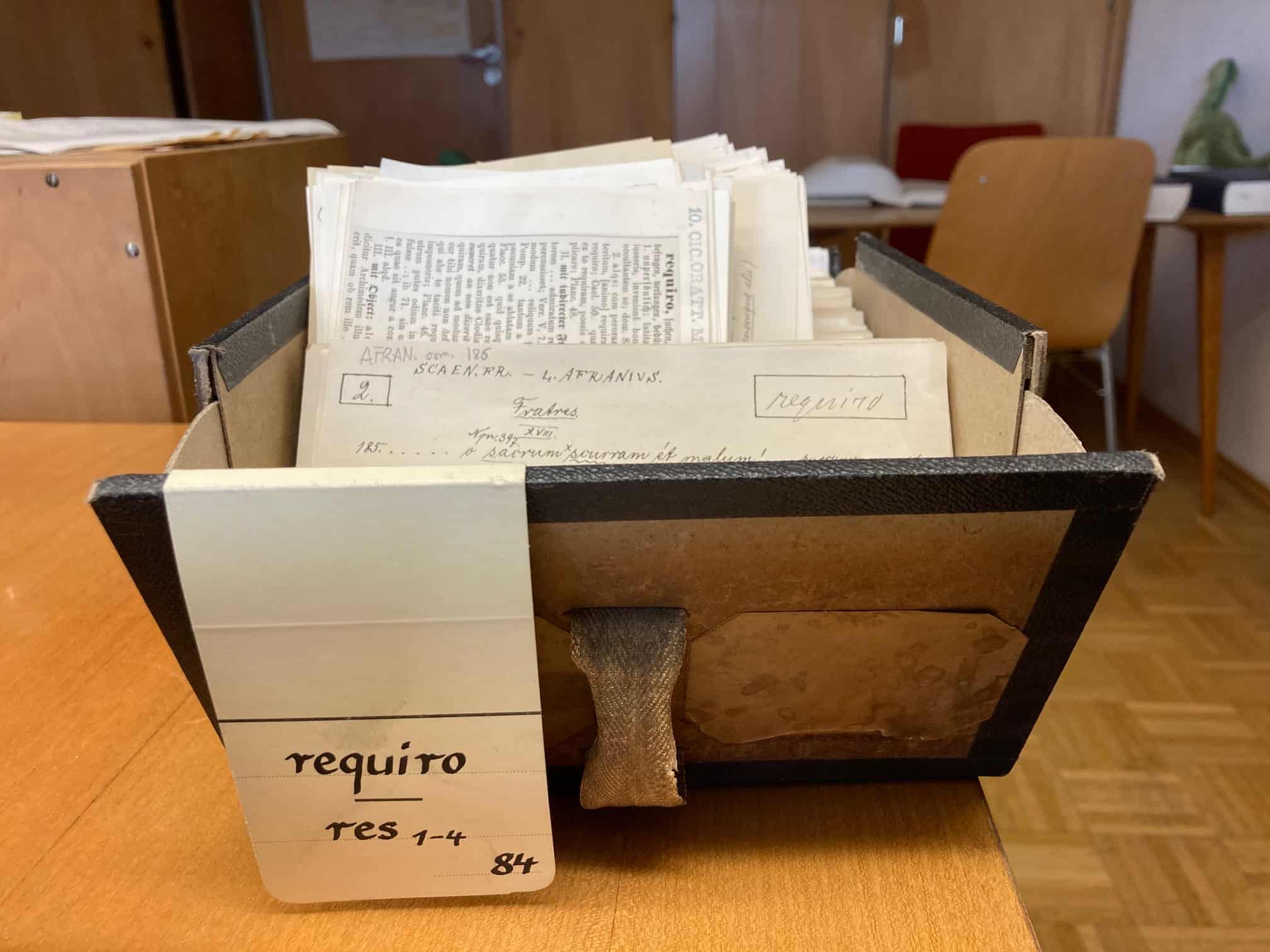

Arranged alphabetically and kept in long, thin boxes the slip archive is a treasure trove detailing every instance a Latin word has ever shown up in history. “At the moment I’m working on the word ‘requiro’ which means to seek or require,” explains Gitner. “I have a box from the archive on my desk with around 900 slips in it which details practically every occurrence of that word.”

Gitner refers to ‘requiro’ as a ‘medium-sized word’ rather than a ‘super-big word’. A super-big word – like ‘et’ or ‘res’– tends to be a commonly occurring word and may involve working with 6,000 or more cards which Gitner says can be a daunting prospect, “Working on the same word all the time can be fun but can make you go a bit crazy,” he admits.

Gathering Evidence

When Gitner starts working on a new word the first thing he does is gather the evidence for that word – the slips. He reads through the slips one by one, makes the connections between the different occurrences and at a certain point, feels he’s ready to sketch out the main divisions of the word – the semantics.

Then, as his investigations go deeper and the various meanings become clear to him he starts to type up the word’s meanings within what he calls a semantic hierarchy. Depending on the word, this process can take years, months or just days. Once an entry has been completed, the article is then painstakingly edited for accuracy by other members of the team – and eventually, by a committee of outside experts.

For example, online tools are used to check the evidence on the slips and the team uses databases of inscriptions and papyri to help them in their work. Also, the dictionary has been available digitally since 2003 – first via CD Rom and now online – bringing a wider audience to the work.

Language that Lives

According to Gitner, there has been a significant and important evolution in how information is presented in the dictionary too. “If you compare articles that were written in say, 1900 to articles written now there’s a big difference,” says Gitner.

Where at one time, article writers merely gave readers the evidence detailing what appeared on the slips, now the writers provide deeper meaning, interpretation and context.

“Giving just the raw data is faster for us for sure but it’s less useful,” says Gitner. “We now give a more elaborate presentation of what the meanings and the sub-meanings of each word are. It’s richer and more precise and hopefully, more valuable to the scholar.”

“[T]he scale of the project gives us the space and opportunity to say what we’re not sure of too.”

Gitner also believes it’s vital that he and the other scholars working on the dictionary continue to point out areas of uncertainty – for example, where the meaning of a word is ambiguous or disputed or where the text is questionable. Another important factor distinguishing TLL from a standard dictionary.

“Normally, a dictionary just tells you what words mean – and of course we do that – but the scale of the project gives us the space and opportunity to say what we’re not sure of too,” he said. “This is important because it leaves the door open for further scholarship and it gives the reader choices rather than dictating to them what to think. The dictionary can be a catalyst for more research and this is what makes the dictionary a living thing.”

A Life’s Work

Having joined the TLL team initially on a short-term contract as a visiting research fellow from the US in 2012, Gitner returned to Munich in 2017 to work on the dictionary full time. So what does he get out of the work?

“My favourite word so far has been ‘regina’, he enthuses. “It’s a word that you think you know – it means queen – but then the deeper you go you find more. It can mean any woman in the royal family, including princess or queen mother – it can also refer to men. I’m especially proud of the appendix listing four distinct Hebrew words all translated as ‘regina’ in the Latin Bible.”

Gitner likens working on the dictionary to be like piecing together a huge incredibly complex puzzle – a puzzle that involves him gaining a rich and stimulating insight into how the Latin language has evolved.

“Working on the dictionary gives you a much broader sense of antiquity as a whole,” he said. “There’s something humbling about contributing to a project on which so many scholars have worked – that I may never see the end of. To be part of something bigger than myself.”

***

A new online version of Thesaurus Linguae Latinae is now available from De Gruyter. TLL’s digital makeover is the result of a close working partnership between the publisher and the dictionary’s users and editors. Available via individual and institutional subscription, the improved online dictionary is now fully searchable and more readable than ever before – opening up Latin scholarship to more readers and researchers.

[Title Image by N p Holmes via Wikimedia Commons]