From Local Archive to Digital Collection: Discover Primary Sources on Brazil’s Rich Film History

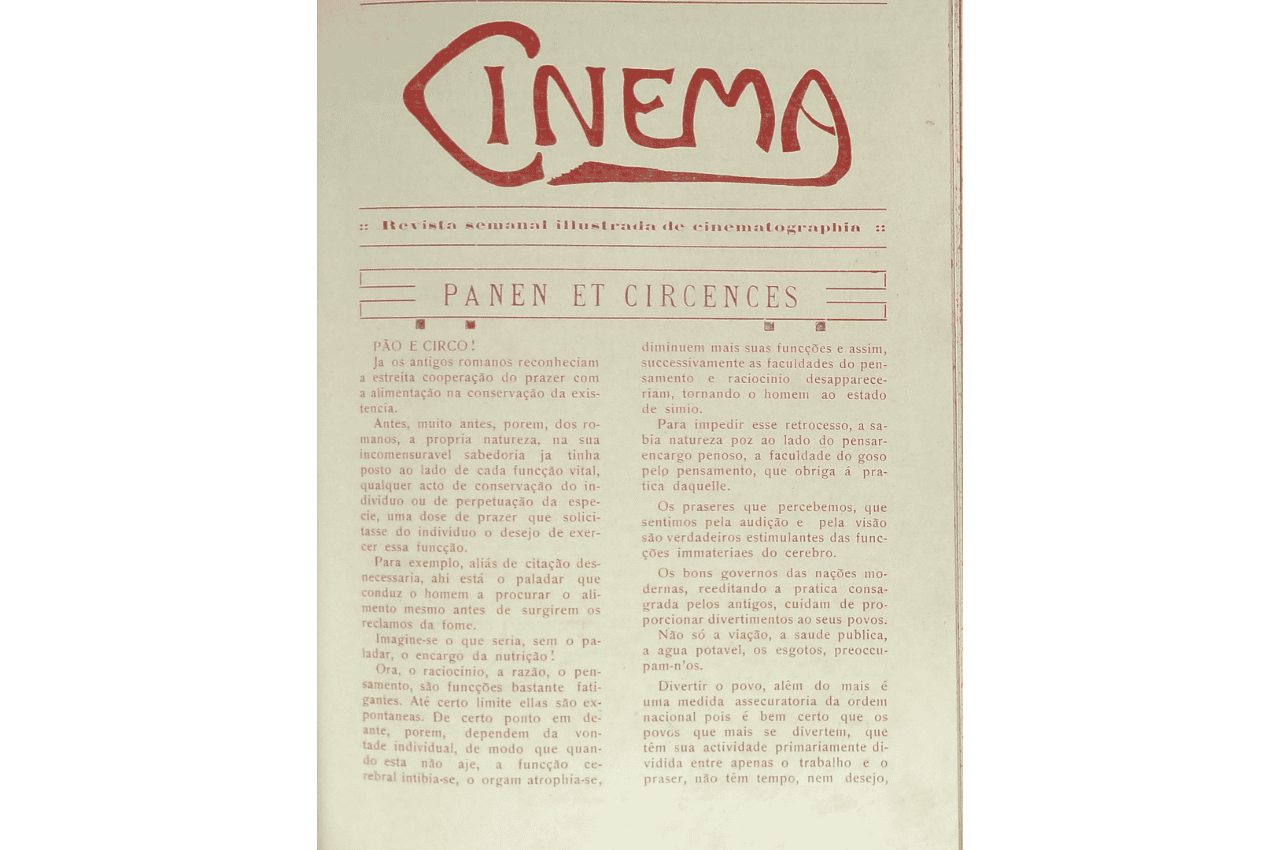

From the 1910s to the 1960s, cinema was one of Brazil’s most popular forms of entertainment, rivalled only by radio. De Gruyter Brill’s Classic Brazilian Cinema Online collection brings together digitized issues of over 60 film magazines from 1913–1974.

Classic Brazilian Cinema Online is, in fact, just one small part of Brill’s unique and extensive collection of online primary sources. This invaluable tool for historians and other researchers provides access to thousands of digitized documents spanning various humanities subjects, area studies and international law. The Latin American Studies subject area is home to not only to Classic Brazilian Cinema Online, but also counterpart collections for Mexican and Cuban cinema.

Brazilian cinema gained international acclaim through the Cinema Novo of Glauber Rocha, Nelson Pereira dos Santos and other directors in the 1960s. Yet Brazil produced numerous films throughout its various regions since as early as 1896. By providing easy online access to more than sixty Brazilian movie magazines, stretching from the 1910s to the 1960s and early 1970s, Classic Brazilian Cinema Online offers a panoramic view of this history, greatly expanding the number of sources available to researchers. Many of the magazines survive in only a few or even single copies and were therefore not previously accessible.

Rafael de Luna Freire, film historian at Fluminense Federal University, edited this collection. Here, he explains why it offers researchers and students a unique look into Brazil’s cinematic past.

De Gruyter Brill: What makes this collection so fascinating?

Rafael de Luna Freire: Brazil has a rich film history, but many of the early films have been lost. The hot and humid tropical weather has damaged a lot of films. Film magazines therefore offer an important window into which films were made in the country, how they were received by the public and critics, and Brazil’s cultural history more broadly.

DGB: What is the impact of this collection on scholars interested in Brazil’s film history?

RLF: Not many film magazines remain. Before this collection existed, researchers were limited to the digitized archives of our National Library. Other archives existed but could only be consulted in person. In a country as large as Brazil, this could be expensive and time-consuming.

Many of the magazines in these archives had been sourced from readers and were quite fragile. It was very important to digitize what was left so that the materials were protected and people could access them regardless of their location.

DGB: What kind of information can researchers discover in the archive?

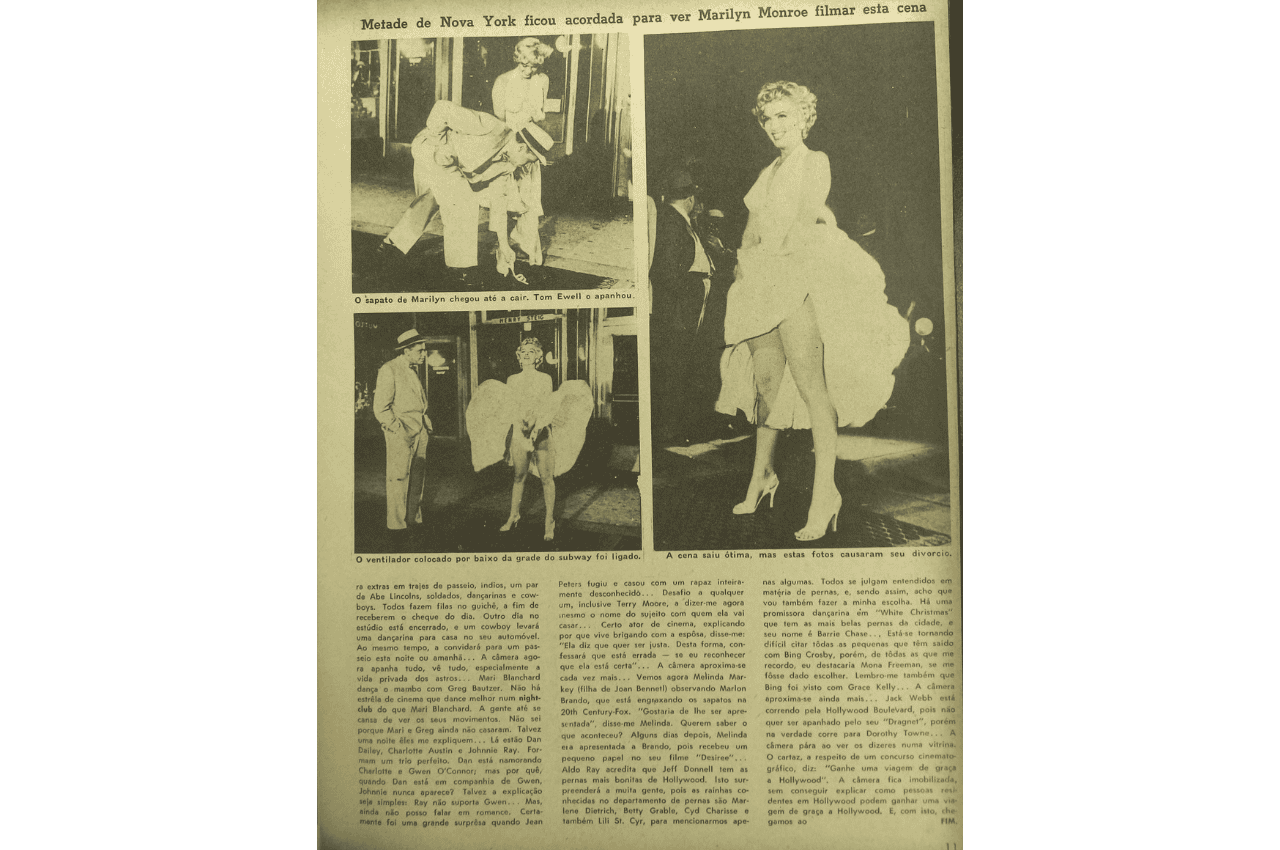

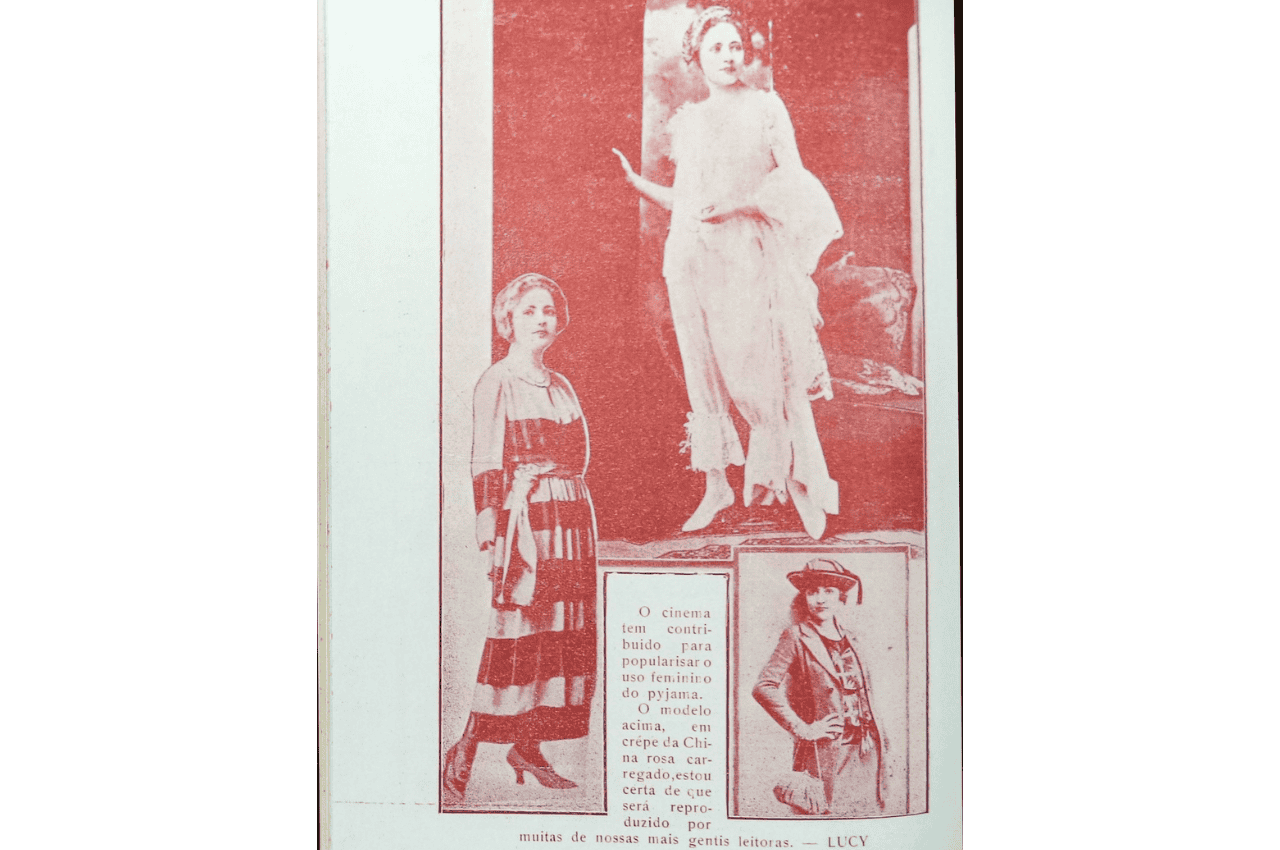

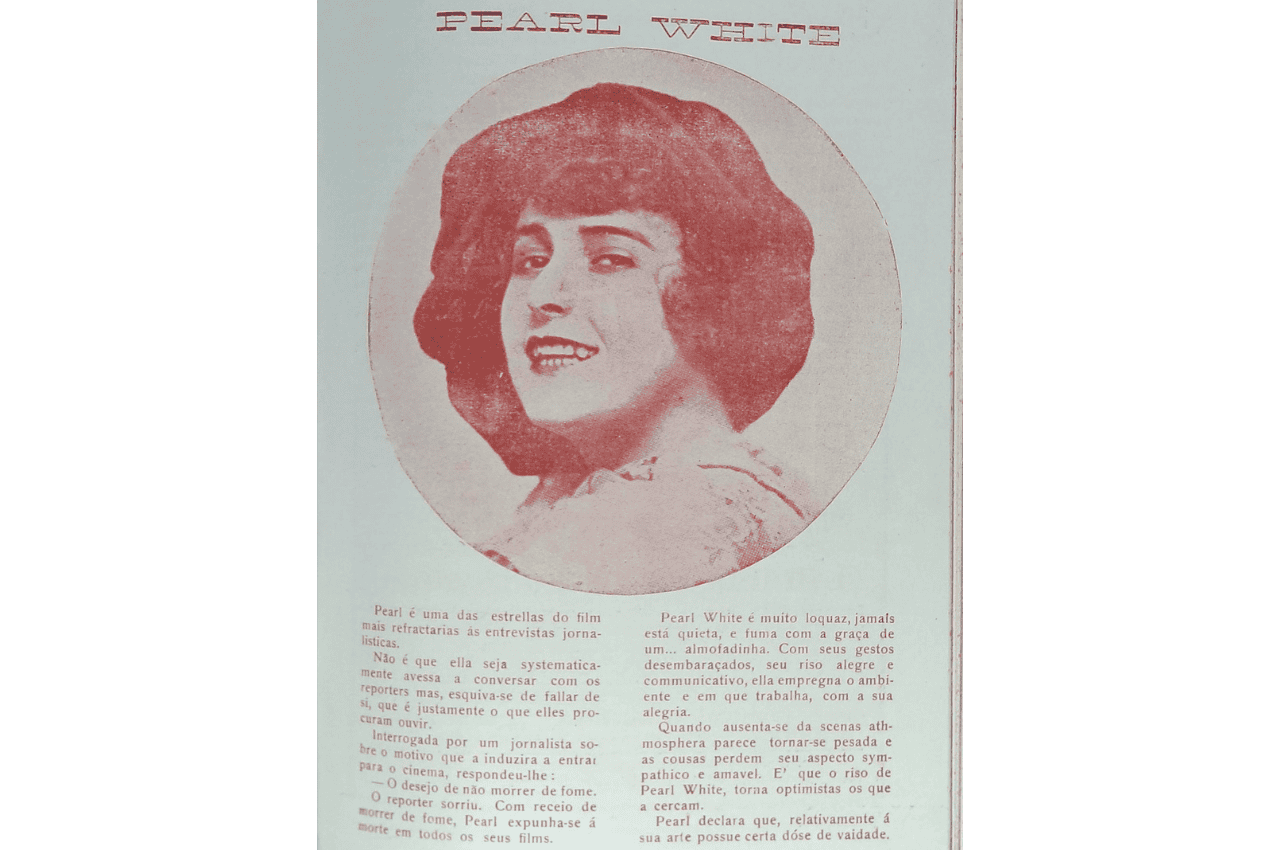

RLF: The magazines contain a wealth of material for different fields of research – fandom and stardom, for example, are key themes. After World War I, Hollywood stars were an important influence on Brazilian culture, even shaping local beauty standards, including the trend for whitening skin.

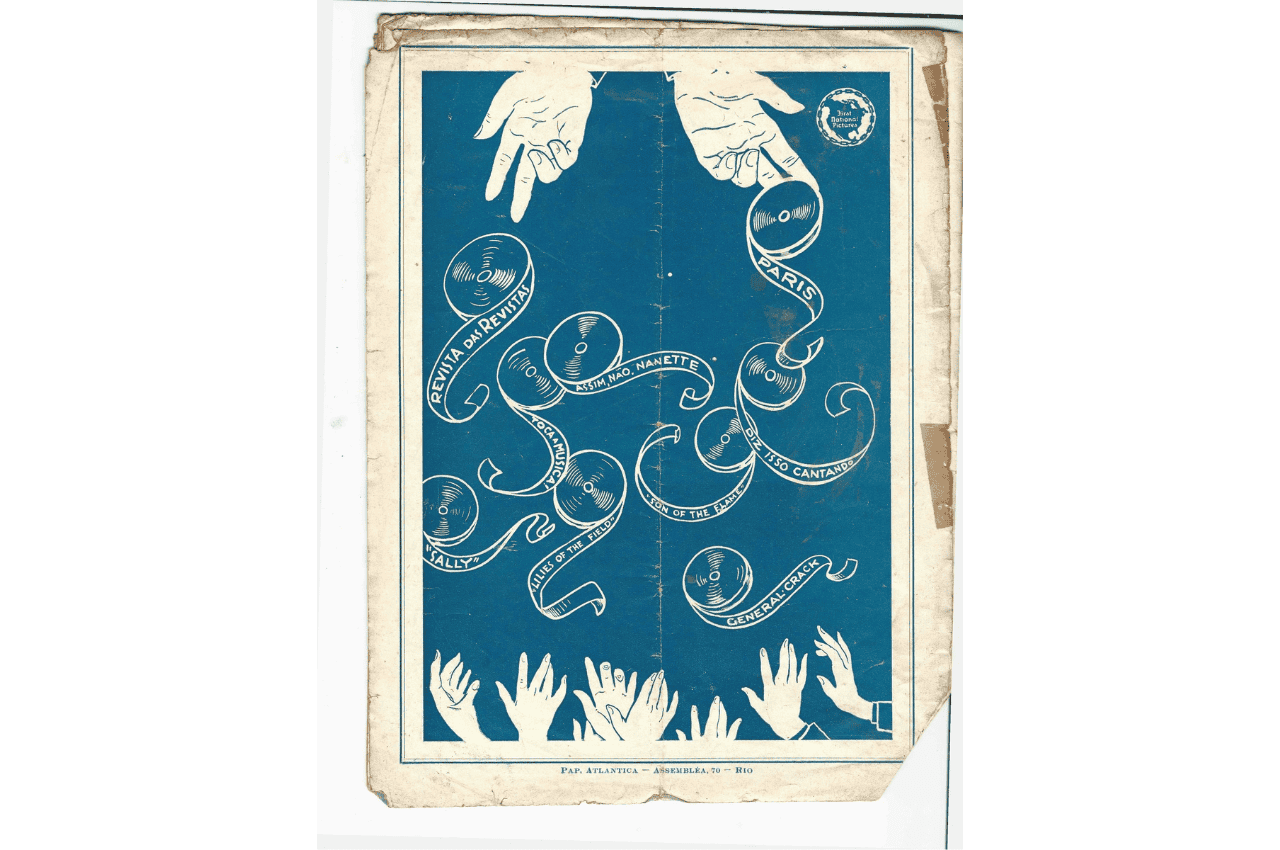

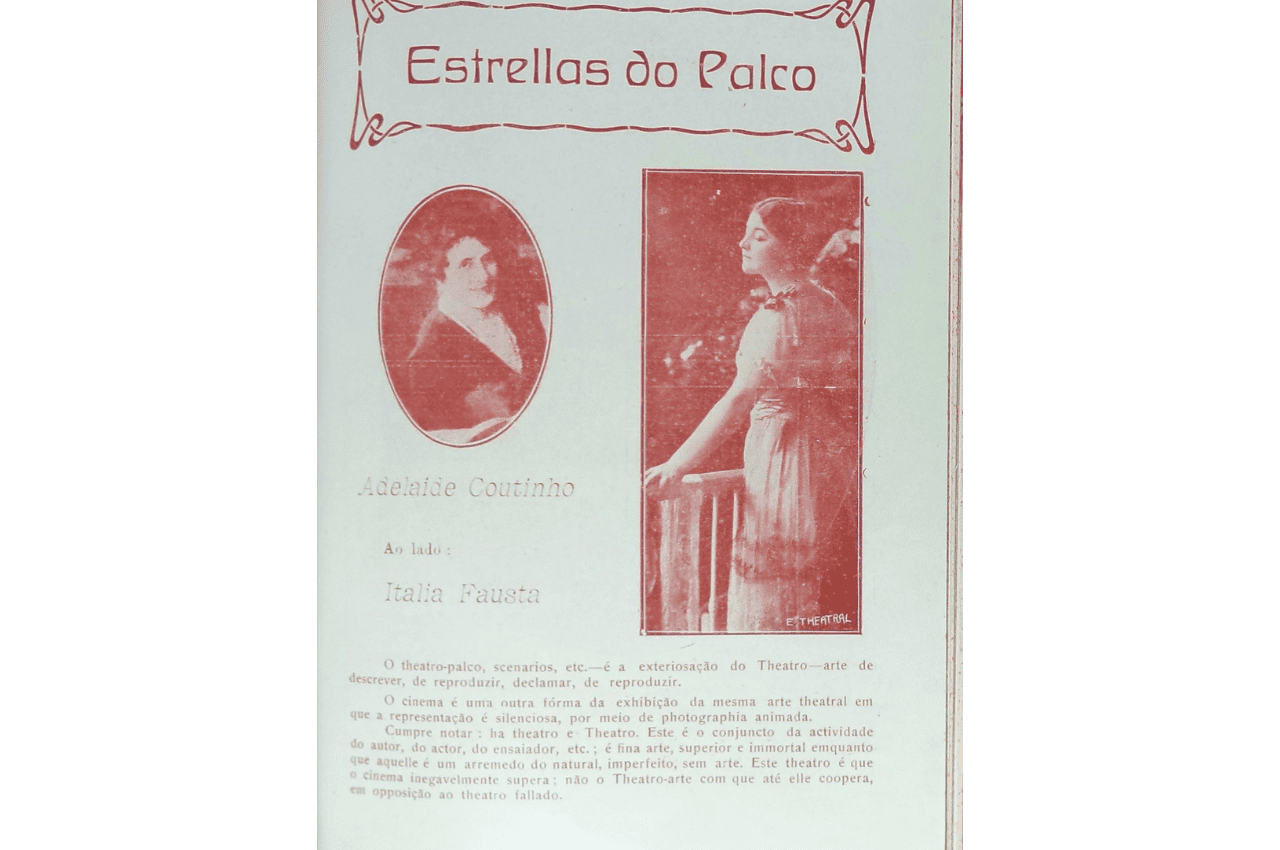

Most titles also covered theater and music. And since they were often targeted at women, the advertisements inside offer interesting insights into Brazilian cultural history. Some of the magazines are very beautifully illustrated, so they are also relevant to the study of graphic arts. Quite a few colleagues have told me they have used the archive in their research.

DGB: Why is Brazilian cinema so important in the context of global cinema?

RLF: Despite challenging conditions, the Brazilian film industry has consistently produced films on a scale comparable to that of Europe or North America. It’s quite an interesting market, particularly given the language difference with the rest of South America. This makes it easier to study Brazilian cinema alongside other countries in the so-called Global South, such as India or China.

Brazilian films remain niche, compared to Hollywood’s dominance, but international recognition can help push certain films out of that niche – for example, when Ainda Estou Aqui (I’m Still Here) won the Oscar for Best International Feature Film last year.

DGB: Can we draw any lessons from the collection that are relevant for Brazil today?

RLF: Absolutely. Today there is a lot of discussion on questions of racism and misogyny, helped by the rise of collectives of black and female filmmakers. It can be very useful to study how race and gender were treated in the past and contrast these findings with the situation today. Many under-represented filmmakers are now trying to rewrite the dominant narrative of film history by shedding light on black and female filmmakers from the past, and these magazines can help them in that research.

[Title Image: Street view of Cinema Pathé, 116 Central Avenida, Rio de Janeiro. Taken in 1926 by Augustus Malta. Public domain image via Wikimedia/Instituto Moreira Salles.]