The Forgotten History of the US-Mexico Border Wall

President Trump’s plans to build a wall is only the latest in a long line of attempts to close the U.S.-Mexico border. But originally, these attempts were never meant to fence out Mexicans. Instead, they targeted a completely different group of immigrants.

Proponents of a US-Mexican wall see the vast land stretching 1,989 miles between Mexico and the United States as an open door for undesired immigration. But President Trump’s controversial plans to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border are just the latest step in a long history of trying to close this particular boundary to illegal immigrants.

“Anti-Chinese policies were essential in transforming the border from a mere line in the sand into a thoroughly controlled space.”

Few people are aware that in the beginning these attempts were not directed at Mexicans. Instead, they were meant to keep out a completely different group of immigrants: the Chinese. Indeed, anti-Chinese policies were essential in transforming the border from a mere line in the sand into a thoroughly controlled space – a front line aimed at keeping out migrants.

Chinese Immigration and the Chinese Exclusion Act

Chinese immigration to the United States began in the mid-nineteenth century. Many Chinese were seeking their fortune during the Gold Rush or served as workforce for the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad.

However, racial prejudice against the supposedly cheap laborers from overseas led to the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, the first federal law excluding immigrants on a racial basis. This exclusion was soon applied to migrants from other Asian countries (and upheld until as late as 1965!). Denis Kearney, leader of the Workingmen’s Party of California, popularized the slogan “The Chinese Must Go” and advocated a fierce anti-immigration policy against the Chinese.

Many Chinese attempted to enter the country despite the ban, either because as merchants or students they were eligible for exceptions, or simply because they wanted to return to the U.S. after a visit to China. People arriving by ship from China were often held for weeks or months at the Detention Center on Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay. The Center was often called the Ellis Island of the West, but chances of entering the country were really much lower than via the New York Bay.

“People arriving from China were often held for weeks or months at the Detention Center on Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay.”

The land borders in the north and south were significantly better options for a successful border passage. The U.S.-Mexico border became the more popular one after Canada passed its own Chinese exclusion laws.

From Line in the Sand to Guarded Door

The U.S.-Mexico border thereby became an important passageway into the U.S. for Chinese. The boundary itself was sketched out in 1848 after the end of the Mexican-American War. At that time, it crossed mostly uninhabited desert. Marked by the Rio Grande in the east and small border monuments in the west it was merely an “imaginary line” which did not get much attention in the years following its establishment.

But all of this changed with the Chinese Exclusion Act.

“The Chinese were the very first group of migrants who had to carry identification documents and certificates to enter the country.”

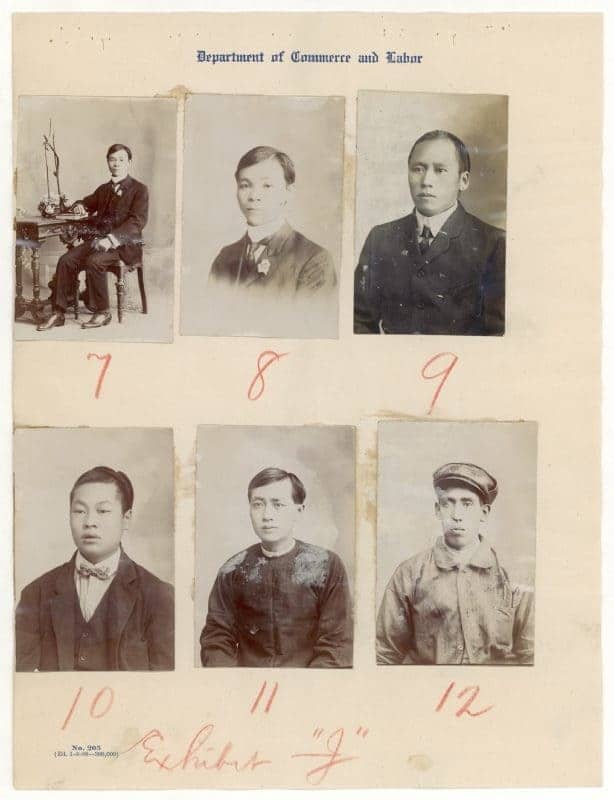

Laws had been passed to curb people’s mobility before. There had been laws to impede the border crossing of anarchists or prostitutes, for example. But keeping out Chinese immigrants posed a whole new challenge to border enforcement. One crucial problem for authorities was the identification of Chinese, who – according to many contemporary commentators – all looked the same.

This is why the Chinese were the very first group of migrants who had to carry identification documents and certificates to enter (or remain in) the country. Chinese immigrants’ certificate documents predated the American visa system. Chinese who were already in the country and could not produce the so-called Section 6 Certificate were in constant danger of deportation – a situation that sounds awkwardly familiar to us today.

New technologies like photography became an important tool to control Chinese migration and identify individuals. Chinese had to undergo physical examination and photographical documentation. We know from photographs that some Chinese attempted to avoid detention by dressing up as Mexicans or Native Americans.

Other technologies were soon added to the repertoire of border enforcement to keep an upper hand in the constant warfare against illegal Chinese immigrants. Authorities increasingly used planes to inspect the borderland from a bird’s eye perspective and trace migrants’ movements in the sand. A large administrative apparatus emerged, ultimately leading to the birth of the Border Patrol as a specialized branch in 1924 with a then-immense budget of one million Dollars.

Contemporary newspapers and magazines were filled with reports about brave border patrolmen defending the nation against intruders – thereby linking the federal officers to the ideal of the masculine cowboy.

To be sure, the Mexican Revolution and the smuggling of goods also increased the importance of border control. But in regard to migrant movement, no group played an equally large role as Chinese. Contemporary commentators often spoke of smuggling rings and organized traffickers that helped to bring Chinese across the border. In this, they were comparing Chinese to other smuggled goods like alcohol or guns.

Borders Produce Barriers inside societies as Well

In public debates, the term “illegal immigrant” soon became a synonym for Chinese non-citizens. The stigma of being in the U.S. illegally and of not being a part of its society affected every single Chinese in the country. The border regime that emerged as a result of the Chinese exclusion was instrumental in spreading the stereotype that all Chinese were illegal immigrants.

As the history of Chinese migration shows, closing the border to migrants never occurs on a purely territorial level but produces barriers inside societies as well. Which groups are affected by exclusion and racial prejudice – Mexicans, Chinese, Irish, Muslims, or others – is bound to change over time.

[Title Image By Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper, vol. 54 (1882 April 1), p. 96. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons