Bohdan Stashynsky: The Internally Torn Assassin of Stepan Bandera and Lev Rebet

Intrigue and betrayal define the life of Bohdan Stashynsky, a former KGB assassin who risked everything to escape his past. His newly released memoirs shed light on the dark secrets of his espionage career and what led him to break free from the Soviet regime.

This article is republished with the kind permission of the author and the L.I.S.A. Science Portal. Click here for the original German version.

In the late afternoon of August 12, 1961, a handsome 31-year-old man accompanied by a woman of the same age entered the Tempelhofer Damm police station in West Berlin and confessed, in confident German with a Slavic accent, that he was on the run from the KGB and had murdered the exiled Ukrainians Stepan Bandera and Lev Rebet in Munich as an agent of this secret service. He then politely asked the police officers to arrest him and to inform “the Americans.” The astonished policemen initially found it hard to believe his fantastic story. However, because these two cases were still unsolved and because the man was able to provide even the tiniest details about both murders, they arrested him and informed the BND and the CIA.

The defector, Bohdan Stashynsky (Богда́н Микола́йович Сташи́нський, Bohdan Mykolaiovych Stashynski), was a talented but internally conflicted secret agent. There was a reason why he was fleeing from the KGB, probably the most dangerous secret service in the world — even though two years earlier he had been awarded the Order of the Red Banner, the Soviet Union’s highest state decoration at that time, for his service to this institution.

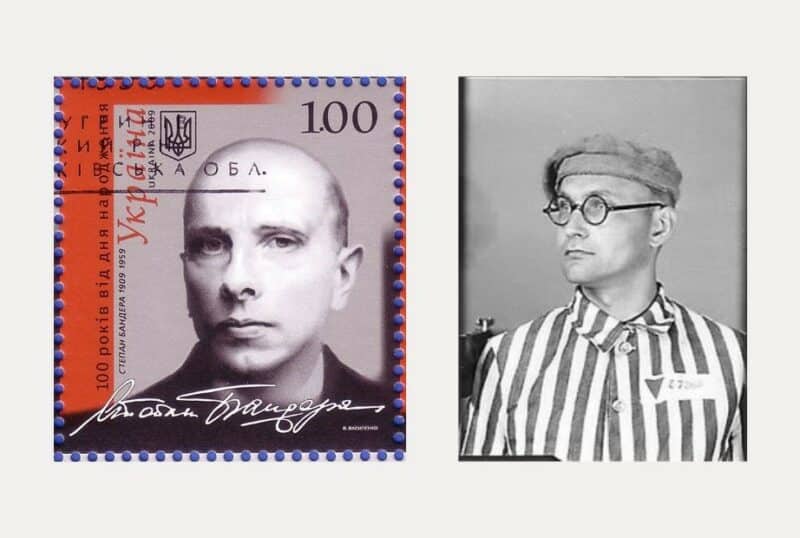

The young KGB agent’s second victim, Stepan Bandera, known today as a controversial Ukrainian hero, was a dedicated fascist and supporter of a genocidal policy aimed at establishing an ethnically homogeneous Ukrainian state in Hitler’s New Europe. Stashynsky’s first victim, Lev Rebet, was well-known among Ukrainian nationalists and among opponents of the Soviet Union. Rebet had long been Bandera’s comrade-in-arms, but after World War II he became his political opponent and a critic of Bandera’s continuing enthusiasm for fascism. Rebet, by contrast, wanted to reconcile nationalism with democracy.

“During his training in Kyiv, he learned the classic skills of a secret agent, such as shooting and spycraft, but also dancing and German.”

Like Bandera and Rebet, Stashynsky also came from western Ukraine. He had become a KGB agent by chance. The NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) had ensnared him by confronting him about a misdeed — he was caught traveling by train from Lviv, where he was a student, to visit his parents in Borshchovych without a valid ticket. Because Stashynsky’s two sisters were working with the Ukrainian underground, this was a very promising decision by the NKVD.

Stashynsky was infiltrated into the structures of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army and successfully tracked down the murderer of the pro-Soviet writer Yaroslav Halan. In 1949 Halan had been killed with an axe at his desk by the Ukrainian nationalist Mychaylo Stachur, even though his apartment was under constant surveillance by the Soviet police. After Stachur was arrested and sentenced to death following a show trial, Stashynsky continued to work for the Soviet secret service.

Because of these extraordinary achievements, Stashynsky, who had interrupted his studies in the meantime, was recommended for service in the KGB by his NKVD superior in Lviv. During his training in Kyiv, he learned the classic skills of a secret agent, such as shooting and spycraft, but also dancing and German. However, due to the Soviets’ flawed teaching methods he never mastered German perfectly, despite its importance for him.

This training process qualified him for service in divided Germany. His transfer was coupled with the creation of an elaborate cover story, according to which he was a late repatriate from Poland. Stashynsky needed a relatively long time to get used to Germany; for the first few months, it seemed to him like a completely foreign country.

“He quickly learned that the Ukrainian nationalists in the group around Bandera were no means less brutal than his employer.”

He lived in East Berlin, where he worked with the headquarters of the Soviet secret service in Karlshorst. After settling in, he traveled several times to Munich to spy on Ukrainian nationalists. There he quickly learned that the Ukrainian nationalists in the group around Bandera were by no means less brutal and ruthless than his employer.

A Tale of Two Murders

Stashynsky’s first victim, Lev Rebet, was found dead by a cleaning lady in the stairwell outside his office at Karlsplatz 8 at around 10:40 a.m. on October 12, 1957. The medical examiner Wolfgang Spann, who carried out the autopsy two days later, diagnosed sudden cardiac arrest as the cause of death. Stashynsky’s second victim, Stepan Bandera, was discovered by his neighbors in the stairwell of his house at Kreittmayrstraße 7 in Munich’s Maxvorstadt district. Bandera, who was known to his neighbors as Stefan Popel, was lying on the floor, gasping for breath. He died a few minutes later on the way to the hospital. Unlike in the Rebets case, the physician who carried out the autopsy, Dr. Laves, determined that Bandera’s cause of death was cyanide poisoning.

Thus the second murder did not quite go according to plan. The weapon Stashynsky used to murder Rebet and Bandera was a pistol specially made in Moscow, which crushed cyanide capsules and sprayed cyanide as a lethal gas at the target. As soon as the poison entered the victim’s respiratory tract, it caused cardiac arrest within a few minutes, but dissolved soon afterwards. An autopsy would not discover any evidence of murder.

How then was the poison discovered in Bandera’s body? The answer to this question has to do with Bandera’s role as a Ukrainian politician in exile and Stashynsky’s nervousness on the day of the assassination. Since Bandera was almost always accompanied by a bodyguard, the KGB technicians in Moscow devised a special pistol that would crush two capsules of cyanide one after the other and spray them as a poison gas. The first portion was intended for Bandera’s bodyguard, the second for Bandera himself. On the day of the attack, however, Bandera was unexpectedly traveling alone, and Stashynsky was so on edge that he sprayed Bandera with two portions of cyanide.

However, what Dr. Laves discovered during the autopsy of Bandera’s body was not sufficient evidence for the Munich criminal investigators to prove that Bandera had been murdered, let alone to identify Stashynsky as the murderer. The Munich detective inspector in charge, Adrian Fuchs, assumed that Bandera had taken his own life because he had fallen out with his wife, who was also a Ukrainian nationalist, over his sexual affairs. Only Bandera’s closest comrades-in-arms, such as Yaroslav Stetsko, a well-known antisemite and the leader of the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations, were certain that the “red devil,” as they colloquially referred to the Soviet Union, had killed Bandera.

Bandera was not the first victim from Ukrainian circles to be murdered abroad by the Soviet secret service. As early as 1938, Yevhen Konovalets, the first leader of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, was killed in Rotterdam by the Soviet agent Pavel Sudoplatov with a box of chocolates containing a hidden bomb. In 1926, Symon Petliura, a soldier, writer and president of the short-lived Ukrainian People’s Republic from 1919 to 1920, was murdered in Paris by Sholem Schwarzbard. Schwarzbard was not in fact working for the Soviet secret service; he was a Zionist who shot Petliura because his troops had murdered several thousand Jews in central and eastern Ukraine toward the end of World War I. Petliura was very unpopular among Ukrainian nationalists because of his alliance with the Polish Marshal Józef Piłsudski in 1920, according to which western Ukraine was to belong to the Polish state. However, after Bandera’s murder the Ukrainians celebrated Petliura as a national hero who, like Bandera and Konovalez, had been murdered by the Soviet secret service.

No Turning Back

But what caused Stashynsky to voluntarily turn himself in to the West Berlin police almost two years after Bandera’s assassination and ask for his own arrest? The answer to this question can be traced back to two developments, both of which began after Stashynsky had been transferred from Ukraine to Germany. The first was his relationship with Inge Pohl, a staunchly anti-communist East German woman he had met at a dance hall in April 1957. They became engaged and finally married in April 1960. For a long time, Inge did not know that her husband came from Ukraine and was working for the KGB. She assumed that he was a late repatriate from Poland. Stashynsky did not want to reveal his true identity to her because of her hostility toward the Soviet Union.

“He realized that his assassinations had caused great suffering.”

Inge’s anti-communism nonetheless had an effect on Stashynsky. He later wrote in his memoirs that under her influence he realized that his assassinations had not “liquidated” two enemies of the Soviet Union but instead had murdered two human beings and caused great suffering to their families.

The KGB itself contributed to Stashynsky’s defection. It had initially refused to agree to his relationship with a “foreigner,” then demanded that Inge live with Bohdan in Moscow, bugged the couple in their Moscow apartment, and finally insisted that Inge abort their child — a demand that the young couple unanimously refused. Stashynsky was only allowed to go to East Berlin to visit Inge in August 1961 because their son Peter had suddenly died in hospital. The young German-Ukrainian couple took advantage of this opportunity. One day before the funeral of their son, who had died far too young, they were able to shake off their Soviet handlers and flee from Dallgow to West Berlin.

Stashynsky’s defection was not only extremely unpleasant for the KGB, but also became an important intelligence affair in the Cold War. The KGB and other secret services of the Eastern Bloc states launched media campaigns accusing BND chief Reinhard Gehlen and Theodor Oberländer, the West German Federal Minister of Displaced Persons, Refugees and War Victims, of ordering Bandera’s murder. Because both men had been National Socialists, the accusation seemed plausible, especially since Bandera and Oberländer had crossed political paths several times during World War II.

Stashynsky’s trial, which took place before the Federal Court in Karlsruhe from October 8 to 15 in 1962, is remarkable from today’s perspective. The judge, Heinrich Jagusch, sentenced Stashynsky to eight years in prison, but the double murderer was already released on December 31, 1966. Jagusch was not only a staunch anti-communist but had also been a member of the Nazi Party for many years. Like the co-plaintiffs from Bandera’s and Rebet’s families, he supported the theory that the primary responsibility for the murders was borne not by Stashynsky but by the KGB chief Alexander Shelepin and the head of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev. Jagusch compared Stashynsky’s trial with the parallel trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem and considered Stashynsky to be just as innocent as Eichmann. His verdict went down in the history of West German criminal justice and is still familiar to some lawyers and historians today. Some Holocaust perpetrators have invoked Jagusch’s decision in order to shift the blame for their criminal acts entirely onto Adolf Hitler or their superiors.

Nobody knows exactly what happened to Stashynsky after his release. His relationship with Inge Pohl broke up, even though Stashynsky was obviously no longer a supporter of the Soviet Union. According to Mike Geldenhuys, a general in the South African secret service, Stashynsky built a new life for himself in South Africa, but other rumors are circulating as well. Stashynsky’s memoirs, which he wrote in prison, were published by De Gruyter in June of this year.

Translated by Laimdota Mazzarins.

[Title image by THEPALMER, via Getty Images.]