Beyond Individual Suffering: Mental Health and Intersectionality in Literature

Literature reveals mental health as a social issue, not just an individual one. By amplifying patients’ voices and exposing systemic inequalities, it helps us understand how culture, class and power shape our collective psychological wellbeing.

When we read narratives about mental illness – whether in the literary canon, memoirs, or social media posts – we’re engaging with more than just individual stories of suffering. These representations reveal complex intersections of power, privilege and discrimination that shape how mental health is understood, diagnosed and experienced across different social positions.

The Politics of Mental Health

The cultural theorist Mark Fisher argued that capitalism has fundamentally transformed how we understand mental distress. What he termed the “privatization of stress” describes how mental health has been reframed as an individual responsibility rather than a social concern. This shift represents a “depoliticization of health” – mental crises become personal failures instead of symptoms of broader societal problems.

“Mental crises become personal failures instead of symptoms of broader societal problems.”

This individualization obscures crucial questions: What role do social structures play in producing mental illness? How do economic inequality, discrimination, and systemic oppression contribute to psychological distress? By examining mental health through an intersectional lens, we can begin to answer these questions and recognize that mental illness is never purely a private matter.

Literature as Medical Knowledge

Literature both reflects and actively shapes our medical understanding of mental health. Literary texts make experiences of illness visible in ways that clinical descriptions cannot. They explore the subjective reality of psychological distress, the ambiguity between wellness and illness, and the social contexts that medical models often overlook.

The World Health Organization definition of mental health goes beyond the absence of disorder to encompass social wellbeing and the ability to cope with life’s stresses. Literature captures this complexity, showing how health and illness exist on a continuum rather than as binary opposites. Through character development, narrative perspective and aesthetic choices, literary texts can illuminate the gradual positions between ‘completely healthy’ and ‘completely ill.’

Moreover, literary and media representations engage in dialogue with medical texts. They negotiate medical spaces, doctor-patient relationships, and treatment modalities. They can critique psychiatric practices, challenge diagnostic categories, or validate experiences that medical frameworks struggle to recognize. In this way, fiction and memoir function not just as reflections of medical knowledge but as sites where such knowledge is contested and reformed.

“Literature captures this complexity, showing how health and illness exist on a continuum rather than as binary opposites.”

Intersectionality: Understanding Multiple Marginalizations

The concept of intersectionality, developed by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, provides a powerful framework for analyzing mental health representations. Crenshaw used the metaphor of a traffic intersection to explain how different forms of oppression – based on race, gender, class, and other social categories – don’t simply add up but interact in complex ways. Just as an accident at an intersection might involve vehicles coming from multiple directions, discrimination operates multidimensionally.

Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye (1970) demonstrates this intersectional approach to mental health. Pecola Breedlove’s psychological breakdown cannot be understood through race alone or class alone or gender alone. Her mental disintegration results from the convergence of anti-Black racism, poverty, sexual violence, and impossible beauty standards that privilege whiteness. Morrison shows how these systems interact to destroy a Black girl’s sense of self-worth, ultimately leading to her retreat into delusion. Similarly, Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (1963) explores depression through the lens of 1950s gender expectations, while also revealing class privileges that afford protagonist Esther Greenwood access to psychiatric treatment.

Who Gets to Speak? Power and Representation

One of the most critical questions for analyzing mental health in literature is: Who narrates these stories, and from what position? The power to define mental illness, to diagnose it and to speak about it publicly has historically been distributed unequally along lines of gender, race and class.

Medical diagnoses themselves carry hierarchical power structures. Who has access to psychiatric care? Whose distress is taken seriously by medical professionals? Whose symptoms are dismissed or misinterpreted through the lens of racist, sexist, or classist assumptions? Certificates of health and sick leave are never neutral documents. They are embedded in systems of privilege and marginalization.

In contrast, Susanna Kaysen’s memoir Girl, Interrupted (1993) offers a first-person account of psychiatric hospitalization that critiques diagnostic practices from the inside. Kaysen questions her borderline personality disorder diagnosis, examining how young women’s non-conformity becomes pathologized. Her privileged class position grants her both access to elite psychiatric care and the cultural capital to publish her critique, advantages she explicitly acknowledges. More recently, Esmé Weijun Wang’s The Collected Schizophrenias (2019) centers the voice of a Chinese American woman living with schizoaffective disorder, directly challenging stereotypes while examining how racism and gender discrimination shape her interactions with medical systems.

“Medical diagnoses themselves carry hierarchical power structures.”

When narratives center the voices of those actually experiencing mental illness, particularly from marginalized positions, they offer perspectives often excluded from medical discourse. Conversely, representations that position mental illness as something observed from the outside, particularly through privileged perspectives, may reinforce existing hierarchies.

Historical Diagnoses and Social Control

Certain mental health diagnoses have been explicitly gendered, raced, and classed throughout history. Hysteria, for instance, was predominantly diagnosed in middle and upper-class white women in the 19th and early 20th centuries, while enslaved Black people in America were diagnosed with “drapetomania” – supposedly a mental illness causing them to flee captivity.

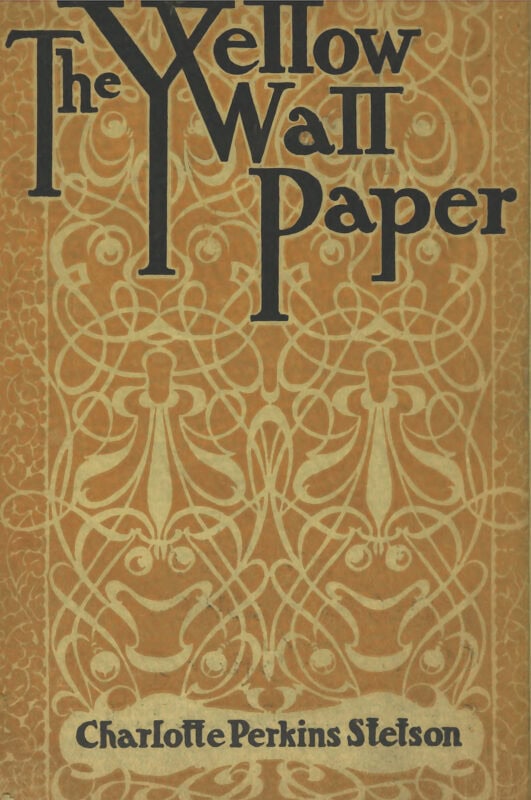

Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper (1892) powerfully illustrates this dynamic of mental health and social control. The narrator’s descent into psychosis isn’t merely personal pathology, but a direct result of the ‘rest cure’ prescribed by her physician husband, a treatment that enforces her confinement and intellectual passivity. Her madness is a form of protest against the patriarchal control of women’s bodies and minds.

Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) reimagines the “mad woman in the attic” from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847), giving voice to Bertha Mason as Antoinette Cosway, a white Creole woman from Jamaica. Rhys reveals how Antoinette’s ‘madness’ results from colonial violence, displacement, racism directed at Creoles, alongside her husband’s gaslighting. What Rochester perceives as insanity in Jane Eyre, is framed in Wide Sargasso Sea as a comprehensible response to trauma and oppression.

Contemporary Mental Health Narratives

The landscape of mental health representation has expanded beyond the literary canon. Today, people share their experiences on Instagram, TikTok and other platforms under hashtags like #notjustsad. Autobiographical accounts, documentary films, self-help books and even video games contribute to the broader discourse on psychological distress. Poet Sabrina Benaim’s viral spoken word piece Explaining My Depression to My Mother (2014) exemplifies how digital platforms create new spaces for mental health narratives. Her performance has been seen millions of times, reaching audiences who might never encounter poetry in traditional venues.

These contemporary representations often explicitly engage with medical perspectives, discussing therapies, medications and psychiatric institutions. They also frequently incorporate social critique, positioning exhaustion disorders like burnout and depression as symptoms of broader problems: neoliberal workplace cultures, economic precarity, systemic racism or gendered expectations.

Toward Political Understanding

“By reading mental health narratives through an intersectional lens, we move beyond understanding mental illness as individual pathology.”

Recognizing the intersectional dimensions of mental health in literature means acknowledging that psychological distress is always political. It’s shaped by who has power, who has resources, who is believed, and who is marginalized. Literary and media representations can either reinforce these inequalities or challenge them by centering marginalized voices, critiquing systemic causes of distress, and imagining alternative possibilities for care and community. Mental health representations reference and build upon each other, forming a cultural conversation about psychological experience that spans multiple media and genres. This discourse both reflects and shapes how societies understand mental wellness and illness.

By reading mental health narratives through an intersectional lens, we move beyond understanding mental illness as individual pathology. Instead, we can recognize it as a phenomenon deeply embedded in social structures – and potentially transformed by changing those structures. This is the substantive contribution of literature to mental health discourse: not just describing suffering but illuminating its social contexts and political dimensions.

Learn more in this related title from De Gruyter Brill

[Title Image: Melankoli II, Edvard Munch, 1898. Public Domain via Wikimedia.]