Who was Christine de Pizan? In Conversation About an Extraordinary Medieval Trailblazer

One of the first professional female writers of the Middle Ages, she possessed extensive knowledge of military tactics and advocated for women’s equality centuries before the feminist movement. We interviewed scholars Earl Jeffrey Richards and Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski about the unusual life and career of Christine de Pizan.

This interview is part of a series of blog posts centered around Women’s History Month.

Although she died almost 600 years ago, Italian-French writer, strategist and historian Christine de Pizan (1364–c.1429) continues to captivate medievalists and laypeople around the world. On the occasion of Women’s History Month, we take a look back on the life and work of this extraordinary figure of the Middle Ages.

Born in Venice as the daughter of a physician and astrologer, Cristina da Pizzano moved to Paris in 1368 when her father accepted an appointment at the French court. At the age of fifteen, she married Étienne du Castel, a notary and royal secretary, with whom she had three children. After her husband died of the plague in 1389, Christine began a remarkable career as a court writer for King Charles VI of France. By 1400, she had become a distinguished and sought-after author, her work being received at the upper echelons of society and later translated into multiple other languages. She was also an advocate for women’s education and defended the virtue of women, notably in her renowned work Le livre de la cité des dames (The Book of the City of Ladies, 1405).

Last year, De Gruyter published her highly influential military and warfare treatise, Le livre de faiz d’armes et de chevallerie (Book of Deeds of Arms and Chivalry, 1410) together with its contemporary German translation, edited by Earl Jeffrey Richards and Danielle Buschinger.

We wanted to learn more about Christine de Pizan’s rise to the top, her stance on women’s place in history, the origins of her military expertise, and much more. So, we got together with two leading “Christine experts”: Earl Jeffrey (Jeff) Richards, Professor of Romance Literatures at the Bergische Universität Wuppertal, and Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski, Distinguished Professor Emerita at the University of Pittsburgh and President of the Medieval Academy of America in 2020/2021.

Alexandra Koronkai-Kiss, Editorial Communications Manager at De Gruyter, conducted the interview, which is also available as a video and podcast.

VIDEO

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

PODCAST

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from SoundCloud. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

You can find our podcast also on Spotify and Apple Music.

TRanscript

Alexandra Koronkai-Kiss: Renate and Jeff, you have both been researching Christine de Pizan for several decades now and published copious scholarly works dedicated to her. Can you tell us about how you discovered Christine de Pizan and what it is that made you “stick with her” through all these years?

Earl Jeffrey Richards: It started in the summer of 1978, just after I finished my PhD in Princeton. I was working with an art historian in Princeton who had been working with George Braziller in New York. She said George Braziller’s daughter-in-law and son have a publishing firm, and they’d like to publish The Book of the City of Ladies – translating the book was how I started with Christine. It came from my interest in Franco-Italian literature, literary relations, and it sort of spiraled into everything after that. Renate and I were both students of the same professor, and so we have had a dialogue for decades.

Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski: Yes, I discovered Christine around the same time, but interestingly, not as a feminist, but as a historian. I was working on the story of Thebes, Oedipus and all that for my dissertation, and I discovered Christine as a historian who had written about the story of Thebes. So, this was before I discovered her as a feminist writer through Jeff and The City of Ladies, the landmark translation that he made, which opened up all Christine de Pizan studies. Then, of course, with the growth of feminist studies, I got into Christine much more.

EJR: It really snowballed. Nobody expected it.

AKK: The first thing that struck me about the story of Christine was her extraordinary success as an author. Surely, to become a highly regarded professional writer in the Middle Ages – perhaps especially as a woman – is no small feat. Jeff, you [previously] mentioned the fact that her mother wanted Christine to stick to weaving and spinning rather than learn how to read and write. Can you give us some background as to how, under these circumstances, she became such an established writer of her time?

EJR: She was connected to the Queen’s court. The Queen of France was Isabeau de Bavière, who was actually a German princess – Elisabeth von Bayern, a Wittelsbach princess and the daughter of [Taddea] Visconti from Milan. When Christine, as a Franco-Italian, came to Paris she had a fellow bilingual Italian speaker in the Queen of France. One thing came to another and through this entree into the Royal Court she came into contact with many of the leading intellectuals of the court.

RBK: She must also have had some charisma, I think, because it’s not enough to be a good writer, but she also had to “sell her stuff”. She made a living from her writing – which is the most unusual thing, because all the other writers of the time we know of – Guillaume de Machaut, Philippe de Mézières – they all had appointments at court or at the church. So, they had a guaranteed income. When Christine became a widow, she didn’t. So she started writing for the public when she needed the money, and she managed to get different factions of the court to support her. Especially later, during the Civil War, she walked the line of the different factions and managed to survive with that income from different nobles at the time.

EJR: That’s an extremely important point. Christine mediated between different factions of the court. She was very sensitive to the politics of everything that was going on between France and Germany, France and Italy, France and England.

AKK: So, I suppose it was her background, being a bilingual cosmopolitan, together with her incredibly broad spectrum of expertise that paved the way for her career. Also, she wasn’t “just” a writer, she was a historian too – which you’ve mentioned earlier, Renate – and I was astonished to find the scope of her authorly output. She was also a poet, right? Quite extraordinary.

It is March, which is when we celebrate Women’s History Month, and I was delighted to find that Christine also had an interest in women’s history and historical experiences. For instance, in her work Othea’s Letter to Hector (Épitre d’Othéa), which is what the two of you translated together, there is a particular take on that. Could you say more about that? What does she understand by women’s historical experiences? And what is the significance of that?

EJR: Renate and I came to the perspective that Christine saw a woman’s perspective on the nature of knighthood as extremely important because a woman could bring wisdom to the whole idea of strength. Female wisdom, masculine strength, sapientia et fortitudo. I think Renate can say more on this than I.

“The whole mythological universe is transferred into a Christian context with important female figures representing the male religious ideas.”

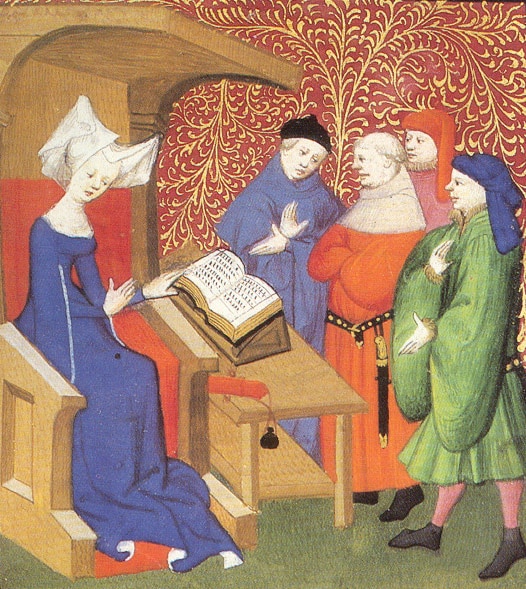

RBK: For me, the most important thing about Othea’s Letter to Hector is the title, because she created the figure of Othea. If you get a chance to look at the cover of our book, you can see the wise woman handing down wisdom to the nobles. So, firstly, she created Othea as sort of an alter ego handing down these lessons of wisdom. And [secondly] I think, Jeff, what you were suggesting was that she’s redefining knighthood with an infusion of sagesse, of wisdom. That will become more visible later in Le livre de faiz d’armes, but there are also a number of big female figures in the Épitre d’Othéa, and interestingly, three of them represent the Trinity. For example, you have chapters where Diana is interpreted as God and Ceres as the Holy Spirit. Suddenly the whole mythological universe is transferred into a Christian context with important female figures representing the male religious ideas.

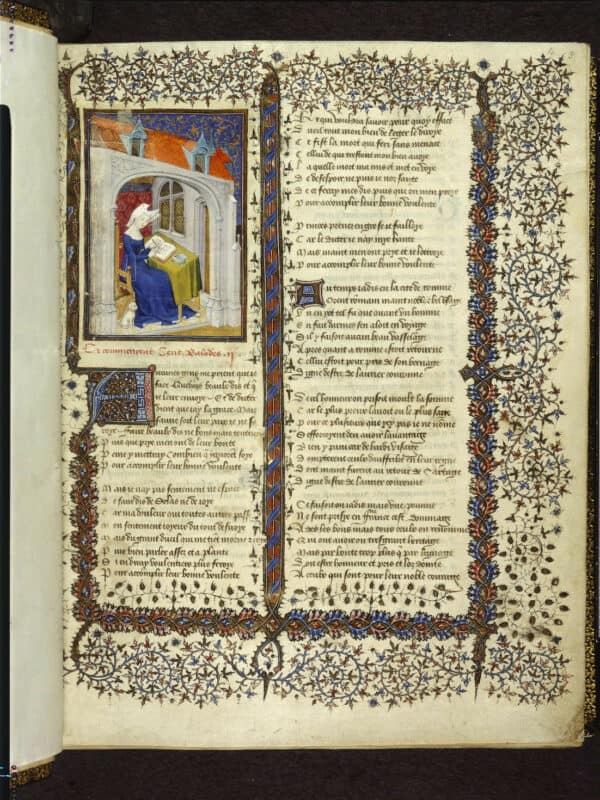

EJR: There’s a very famous miniature showing Diana teaching women to read, where Diana is portrayed as the Virgin Mary with a book, and the other portrayal of Minerva as two goddesses. As Christine says in the Othea, it’s actually one goddess, but she shows two figures: a woman armed and a woman with a book looking like the Virgin.

RBK: Exactly. There are 100 chapters in the Othea, each chapter divided into text, glosse and allegory, and the very last chapter shows us the Sybil, the female prophet teaching the emperor Augustus. So, you couldn’t get any more on what women’s role is in the political life.

EJR: It’s a very polite “Listen, boys.” (Chuckles)

AKK: Stepping back to the Faiz d’armes, the book mentioned earlier, published by De Gruyter: In it, Christine gives the readers very hands-on, practical advice about military tactics and waging war. But, she also raises the matter of a “just war,” even articulating the very concept of a crime against humanity. There is this dichotomy of the humanist and the military expert, if you will. Can you illuminate that? What is this concept of a “just war”?

ERJ: In the first two books of the Faiz d’armes, Christine gets down and dirty in terms of military tactics. Just one very fast example: She talks about how excrement is used as a protection against the newly invented technology of cannons. She says, well, you can fill quilts with excrement and hang them on the castle walls and that way they’ll buffer the cannon shots. Or, you can put excrement on top of siege machines so that the besieged firing fiery arrows will not be able to make them catch fire. That’s totally down and dirty, and she talks about everything technical. Then, in the last two books, she switches completely to talk about very specific terms of military law and war. She had begun with talking about what constitutes a justly fought war, but in the last two books, she talks about specific questions, safe conduct and other things. And then she talks about the treatment of civilians captured. This is where she comes to the question of inhumanity and the use of Greek Fire, which she considered to be a crime against humanity.

AKK: What is the Greek Fire?

ERJ: It’s a forerunner of napalm that you can’t extinguish with water. It goes back to the 8th century and the Byzantines used it in naval combat. And it was used, for instance, in the Siege of Cologne in the 10th or 11th century. The Archbishop of Cologne writes about this as well, so it was well-known. But Christine says that it’s a crime against humanity and you can’t use this against Christians.

RBK: Could I ask you a question, [Jeff]? What kind of research did Christine do? Because she used Vegetius as the source, and then she updated it to the late Middle Ages. Do we know who she talked to or how she found out about all these technical things?

ERJ: She was interviewing people, and she even says this in the book. She interviewed high ranking military officers at court who preferred not to be named. Through a process of elimination, we can identify some of the individuals who were one of the heads of the King’s cavalry, for instance, but it’s really a guessing game. But, she brings in details that are not in Vegetius’ text from the first century in Latin – mostly about infantry tactics. Christine expands Vegetius to speak about siege tactics, and it’s clear that she is speaking to people at court because there are chapters in the Faiz d’armes where she just gives a list of what an army on the move needs. It’s like she’s taking dictation in that case. In the second part of the book, it seems as though she’s engaged in an ongoing dialogue with people at court about legal issues. Her major source here seems to be an author named Honorat Bovet, and he was at court too. Christine seems to have known him, but there’s just an enormous amount of erudition that’s involved here, and Christine is actively asking questions. I don’t know if that’s a complete answer, but it’s the beginning of an answer.

AKK: We’ve mentioned that the Faiz d’armes was translated into German, High Alemannic to be precise, but it was also translated into Middle English. Can you tell us about the contemporary reception of the work?

ERJ: There are over 30 manuscripts of this work, and they divide into two groups: One group specifically names Christine and stays with the format of a woman speaking about war. Then there’s a second group of manuscripts where Christine has been suppressed as the author, in which the initial prayer to Minerva, where Christine speaks about her position as a woman talking about war, has been dropped. But the work was well-known throughout Europe and England. The Middle English translation was done by Caxton himself, the famous printer. Published in 1489, it’s considered to be one of the first bestsellers of the English language. The Middle High German or High Alemannic translation is either from 1353 or 1383 or 1453 or 1483 – it’s hard to decipher the numbers. It was done in Bern about 20 years before Bern declared independence from the Empire. It seems to have been received in very specific contexts across Europe at the end of the Hundred Years’ War, and it was well received and widely cited in other sources.

AKK: There is this one manuscript where Christine even writes her own name down. That was something rather uncustomary at the time, wasn’t it?

“She uses the term Je, Christine very specifically to emphasize her position as a woman speaking with erudition and with authority.”

ERJ: She is very keen on making sure that people know it is Je, Christine – I, Christine, who am writing this. Particularly in the second half of the book, the ghost of Bovet addresses her as amie and as Christine. She uses this phrase later, in her last work, when she begins Le ditié de Jehanne d’Arc, a piece of poetry about Joan of Arc: “I, Christine, [who have wept for eleven years in a walled abbey …]” She begins with Je, Christine, and she uses that term very specifically to emphasize her position as a woman speaking with erudition and with authority.

RBK: When you look at the tradition of women writers in the Middle Ages before Christine, they were mostly religious writers. She’s the rare secular writer after Marie de France from the 12th century. Didn’t Marie also say “Marie, je suis de France,” if I remember it correctly, centuries before? (Jeff nods)

There’s a gap between the 12th and the 15th century where we have no named record of any secular women writers. There are some female troubadeurs, but we don’t really know much about them. So, Christine’s the first writer of whom we have a biography, a history, and we know so much more about. Also, the fact that she supervised the production of her manuscripts: As you point out, the illuminations, for example, in most of her manuscripts were done under her supervision. When you have these images of women giving wisdom, for example in the Othea, we can see the designer behind that, I think.

ERJ: And here the Je, Christine part also involves an incident that she describes, of becoming a writer. She says her husband died and she was a widow, and that fortune came to her and transformed her into a man. She says, “I was a true man. I was a perfect man, but I still kept my name, which contains the name of the most perfect man.” This is where she is a secular writer but also incorporates religious elements, where she wants people to know: I am a kind of universal human figure, I am a woman who has become a man. It’s an amazing jump, you could say.

RBK: What I found so striking was that when she starts The City of Ladies, she abandons this idea of having become a man. I would just want to give one little concrete example: When she talks about her transformation into a man in the Mutation of Fortune, she says, “I was stronger and lighter” – plus fort et léger. That’s from Ovid’s text, the transformation of Iphis into a man. Then she uses the exact same wording in the Cité des dames, and says: I am fort et léger, and I’m now going to build the city of women. Now she’s building as a woman, which is just so interesting, as if she is reversing her transformation.

ERJ: And she shows the picture of her lifting stones with the other virtues. In the frontispiece of the cité des dames, you have first the three virtues appearing to her. And then in the facing picture of the frontispiece, you have them all working together on the wall.

AKK: Then there’s also the Queen’s manuscript, where there are some concrete forms of self-representation, or self-portraits as a writer. She’s sitting in her study and has this quite hefty book open, and she’s clearly writing it. That I found quite extraordinary, especially in light of the fact that she was the one supervising all aspects of manuscript production, including these illustrative aspects. You can really see that she had her eyes on her self-promotion, if you will, or at least representation of her authorship as such.

ERJ: She had a unique position, she really was a unique writer. And I think her contemporaries knew that.

AKK: Absolutely. Just an incredibly multifaceted—well, not just writer, but person. I was delighted to have had this opportunity to find out about her a little bit myself and, through this interview, I hope our listeners and readers could too. Thank you very much for taking the time today to reveal all these fascinating bits and pieces about Christine. I’m sure that we could sit here for hours and keep unpacking this wonderful story, but for now, thank you for your time and thank you very much for the interview!

Check out this related title from De Gruyter

[Title image via Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain]