Unbuilding Walls: Interview with Daniel Libeskind

Before the fall of the Berlin wall, Daniel Libeskind already envisioned its end in his design for the Jewish Museum. Now, he talks about ideology, the memory of history, and the future of architecture in Berlin.

This interview originally appeared in the book Unbuilding Walls

GRAFT: In February 2018, Germany has been reunified for 28 years—exactly as long as the inner German border wall existed. It was a structure built to lock people in and to take away their freedom, but in between the wall and its so-called “hinterland wall”, it simultaneously erased all evidence of historical and architectural memory. By now, the space that the Berlin Wall had carved out through the entire inner city has been re- filled and interpreted in many different ways, for example through critical reconstruction—yet another kind of memory, or rather non-memory.

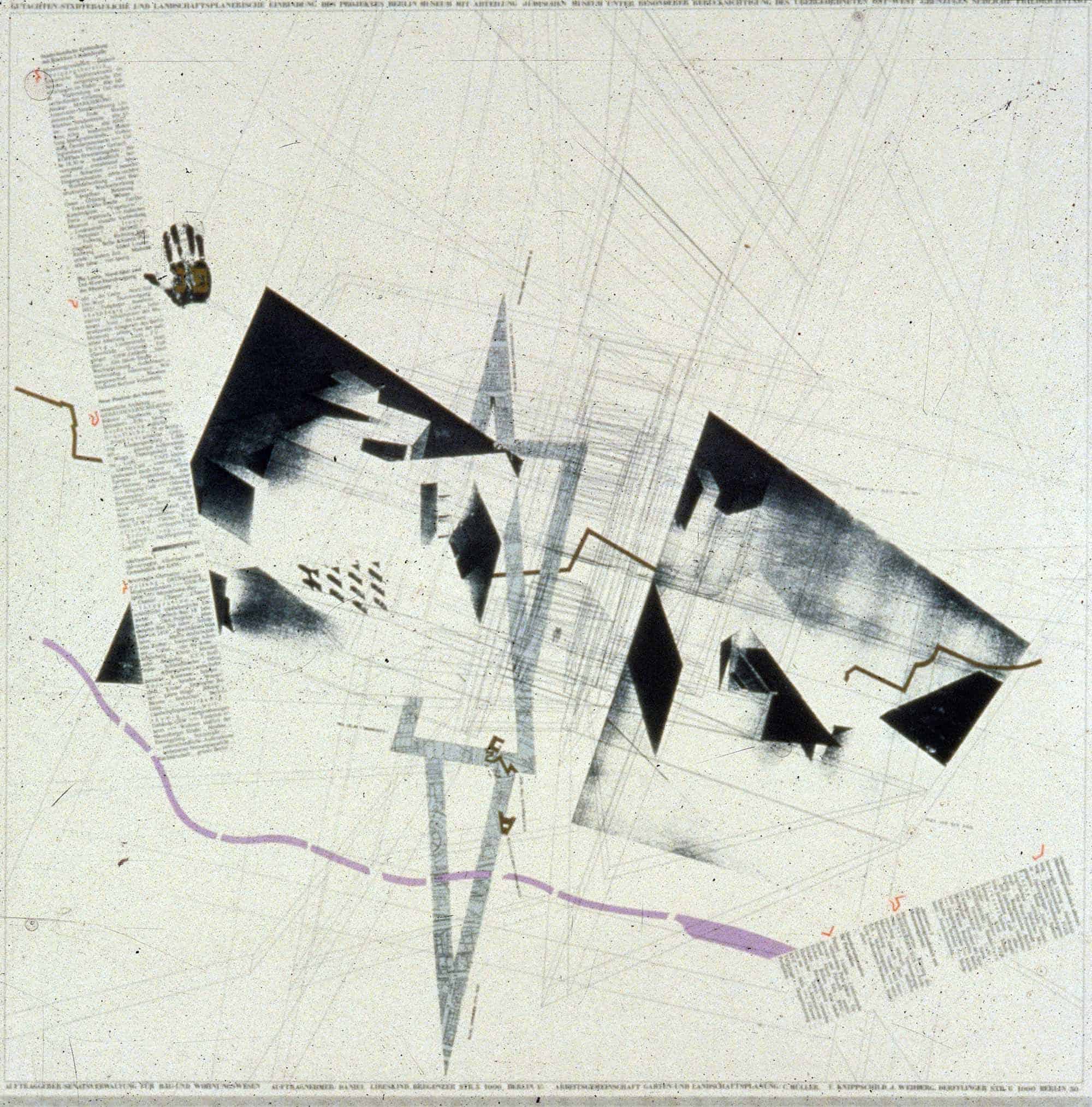

Even before the fall of the Wall, we remember you putting parts of its geometry in your competition proposal for the Jewish Museum, which you built in Berlin not far away from the former border. Why did you do that and how did the analysis of this structure affect the design and your thinking?

“Drawing the Wall in February 1989 felt like demolishing it.”

Daniel Libeskind: Drawing the Wall in February 1989 felt like demolishing it. I remember deliberately orienting the building both east and west rather than just creating the obvious entry, which was, of course, lying in West Berlin. In my proposal, the building would be accessible from the east as well, even though the Wall was still there. I remember being asked in the process why I would ever do such a thing, and I said: because the Wall will not always be there. In a way, the zigzag of history is also part of the city itself, created by the topography of the Wall. Although the Jewish Museum has nothing to do with the East-West division, the topography of the Wall certainly was an echoing element during the design process.

GRAFT: Interestingly many of your projects and competition entries were located very close to the Wall, before and after its fall. How important was the Wall in these others designs, and were architects at the time talking about the fact that the Wall would be coming down and which repercussions its fall would have on city planning?

Daniel Libeskind: On the contrary, all these projects, like IBA and similar plans in East and West Berlin, were rather showing the permanence of the situation. And in fact, I spoke to a very famous historian maybe a week before the Wall came down, who told me that the inner-German border would not disappear in our lifetime. Right until the end of the GDR, there was a competition to show the face of politics in some way—on both sides of the Wall. The border was a very magnetic line for East and West equally—since even in the part of the city, we were still surrounded, hence trapped, bounded by the Wall. The situation didn’t seem temporary at the time.

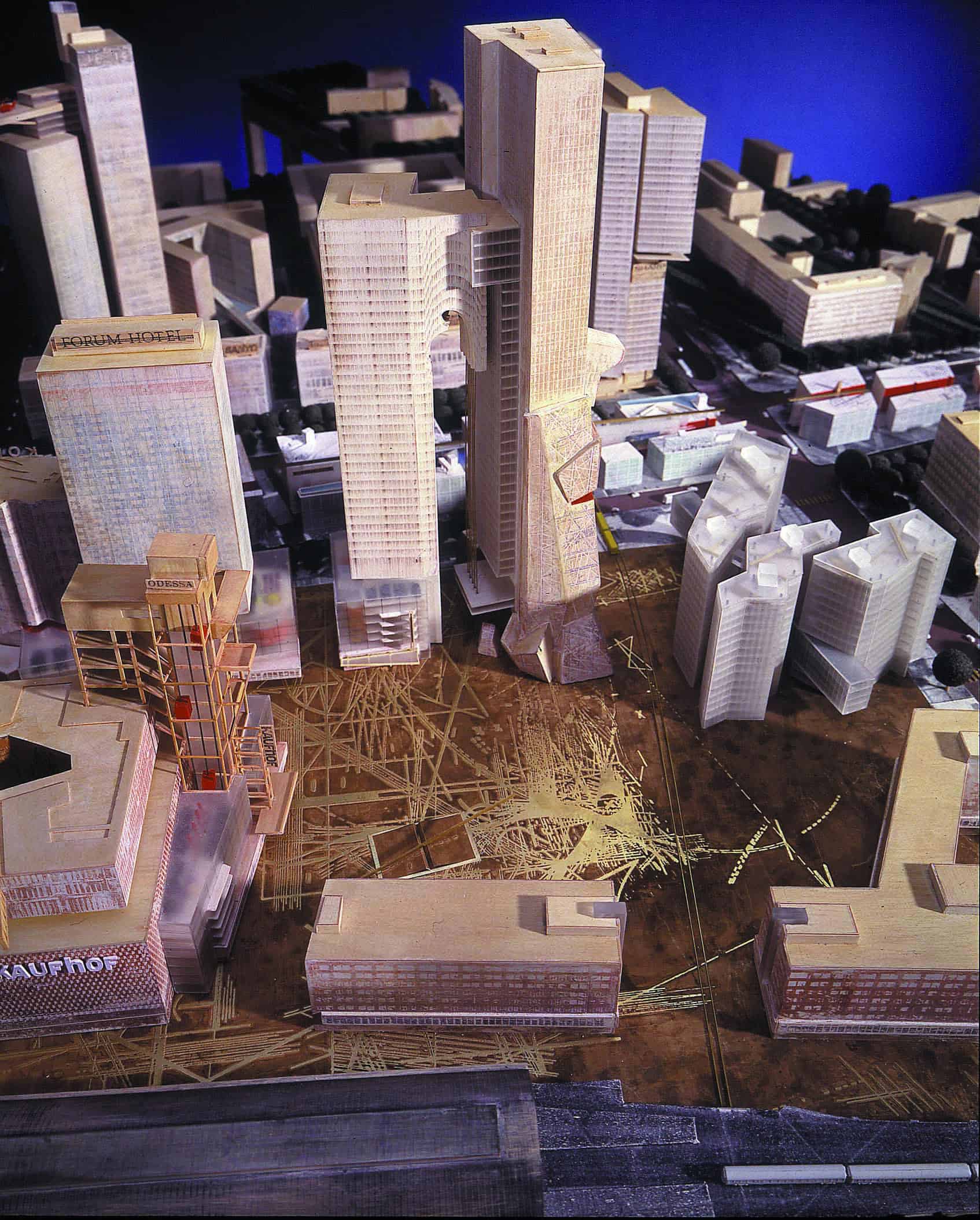

GRAFT: There was a certain magic to the fact that the fall of the Wall hit the city completely unexpectedly—suddenly politics, architecture and public life had to reinvent themselves. Looking at your proposal “City Edge” for Potsdamer Platz in 1991, it looks like more than a design for this specific public area, almost like an interpretation of where the entire city could go architecturally. You treat the different sources of the urban fabric, in particular the baroque heritage and the urban fabric of the Gründerzeit, as two layers among many other equally important ones. While other architects were looking for a strategy to unify and regain a dominant identity, you seemed to be celebrating an invisible utopian idea of diversity. Was that intended?

Daniel Libeskind: I intended it as an actual proposal. I called it the urban wilderness—a way that would guarantee that the city would not erase its history or get falsified by virtual ideas of what it supposedly used to be. Potsdamer Platz in particular was an area that was traversed by forces of history and that could actually be made into the center—a social space and a residential core still fulfilling the high-density requirements, a canvas to invent really. So, I didn’t mean my proposal as a theory at all. It was uncovering traces of a city that was yet unborn—liberating it from the past by immersing itself in the wilderness of its history, not by erasing the past. City planners at the time, however, had the idea that the city should be rebuilt according to 1930s requirements. But you can’t go back to 1933 and erase history as if it had no impact on people’s lives or on the shape of the city. This kind of reconstruction of buildings is a totally anachronistic plan.

There was a short period of time after the reunification, when everybody felt that everything was possible, that the future could really be reinvented.

GRAFT: There was a short period of time after the reunification, when everybody felt that everything was possible, that the future could really be reinvented. A very diverse spectrum of ideas and designs from Zaha Hadid, Peter Eisenman, OMA and even John Hejduk had been planned and realized even before the fall of the Wall, so everybody expected that the positive energy of freedom and reunification was going to be unleashed in architecture as well. However, something completely different happened: all that potential and broad spectrum of ideas, in the end, was funneled down into that one vision of the so-called “critical reconstruction”. Why, do you think, in the following years critical reconstruction, an approach that preferred the traditional framework of rules, was so successful and still dominates the entire debate even today? How do you think the cultural heritage of Bauhaus and modernity and its successes could become so discredited as we have witnessed it in Berlin since 1989?

Daniel Libeskind: It is hard to understand why critical reconstruction became so prevalent. It oppressed the possible development of Berlin for many years, and you can still see its shadows today. One prominent example is the reconstruction of the Schloss in Berlin, a decision that will come to haunt the city in the future. Critical reconstruction was a reactionary ideology that wanted to bring the city right back to 1933 and pretend that there was no other reference point. In my perception, it didn’t succeed because people, history and culture are not like that. These complex correlations cannot simply be manipulated by the reconstruction of streets.

In the end, critical reconstruction was a simple formula, with a retro-vision. One cannot take the complexity of a city and use old plans and start building accordingly. In order to impose such an idea, you need a powerful government. In Berlin, the Stadtbaudirektor (Director of City Planning) at the time was even more powerful than the mayor. So, by virtue of occupying that position, they managed to declare this ideology as the official practice of the city. It was basically a question of power and not an actual intellectual dialog—and power here was exercised in a very authoritative way without much public input.

I was actually surprised how few architects and intellectuals spoke up against it, given the diversity of architecture produced just a few years before. Berlin is really a cosmopolitan, international place with people from all around the world experimenting and creating avant-garde architecture. It went right back to the Gründerzeit though and all these mockeries.

By trying to bring the city back to what it was like in the 1930s, they discredited everything that happened in between—as if the Mies buildings or Hans Scharoun’s architecture, those brave worlds, had not or should have never happened. And simultaneously, as if there had been no catastrophe, as if there had been no Holocaust, no abyss, no void in Berlin.

GRAFT: Right after the Wall came down, everybody wanted its physical reality to disappear. And now, 28 years later, the last remaining fragments are listed buildings with people building museums around it. How important is the aspect of time in this process?

Daniel Libeskind: The aspect of time is very important because it changes our perception of events. People who have a rather authoritarian idea of instant transformation, over and over are proven wrong in the long run. This applies to Warsaw for example, where I just built a high-rise residential next to the Palace of Culture and Science, originally known as the Joseph Stalin Palace of Culture and Science. People definitely wanted to tear it down, but in the end, they agreed to leave it as part of the history, but to restructure the space with more urban life. The general idea was to bring people to the center of the city, because Złota 44 is standing on one of the best pieces of land.

People have to be able to deal with these disasters of history and understand that the memory of history cannot be obliterated. Whatever the memory is, you can’t just pretend it never happened. And that holds true for East and West in Germany for sure.

GRAFT: Much has been said about Kollhoff’s design in comparison to your urban strategy for the Alexanderplatz. You once said that Kollhoff had won and would be defining the development plan but that after 15 to 20 years the Alexanderplatz would be looking more similar to your scheme—and history proves you right. What made you so certain that the idea of stylistic dogma would not succeed in Berlin?

Daniel Libeskind: My idea for the Alexanderplatz was to gradually improve the buildings and urban spaces by bringing recreation, culture and a better sense of public life to it, a kind of homeopathic approach—instead of destroying the existing architectural and cultural history.

You didn’t have to tear down buildings and show the invasive powers of politics. All over again, it was about building a new center of Berlin. No one had any intention really to start all over from tabula rasa, even though that was proposed by the architect. My proposal was more reasonable. It was inspired by Alfred Döblin’s idea of a place for the working people, and not for planners, architects or politicians, and I think that’s exactly what has happened. Nobody tore down buildings, although the development plan is based on Kollhoff’s proposal.

GRAFT: How much, do you think, East German architecture, let’s say socialist design in general, was condemned to be associated with a regime that failed and was responsible for inhumane oppression?

Daniel Libeskind: It was deemed so. But if you really look at those buildings in East Berlin, for example at the Alexanderplatz, they are not so different from buildings in Rotterdam and other cities all over Europe. Most of them are based on a modernist idea, no different from what happened in New York at that time. Lumping architecture with ideology can be a dangerous thing if you just look at a picture and say whether something is modern, old, democratic or authoritarian, when architecturally, there is nothing wrong with these buildings. They are always more than just ideology, they are also economy, society and traces of history.

GRAFT: We are currently seeing more and more examples of architects and people trying to rebuild and reconnect the city. Some of these projects are big successes. But we are also aware of the fact that Berlin and Germany are still divided—socially, economically, culturally. In many statistics, the Wall is still there. Unbuilding the Wall takes much more than tearing down its pieces. Do you believe that architecture can play a vital role in this process?

Unbuilding the Wall takes much more than tearing down its pieces.

Daniel Libeskind: I completely agree—you can pretend to have reconnected the city by demolishing old walls and building new ones. But you cannot erase the walls that remain in people’s minds. One of the reasons why this never works is because sometimes the obvious connection is actually a disconnection. Whereas a certain way of disconnection is a connection. So, I believe, that all those exercises of simply reconnecting the city were really just exercises in physics, not in architecture. They were proofs in physical terms: proof that you can continue a street across the former border again, build the front of a building or put a traffic light somewhere. But that has absolutely nothing to do with socially connecting memories and history. If you are oblivious to the memory of people though, of generations even, then you are bound to create a falsified view that might look ne on the outside, but it will crumble on the inside.

“The connection that was made between East and West after the reunification was a surface connection, and many current political developments are linked to this lack of association, like the return to the right-wing vote and the rejection of the mainstream in the last elections in Germany.”

The connection that was made between East and West after the reunification was a surface connection, and many current political developments are linked to this lack of association, like the return to the right-wing vote and the rejection of the mainstream in the last elections in Germany. In a way, this was inevitable because truth is the daughter of time. The aggressive notion that you can impose continuity and falsify truth, rather than expose discontinuity, has led to this kind of state of mind by people who feel that they have been ripped off. They feel that they have been made into some kind of an exercise, rather than been taken seriously as citizens with a history.

GRAFT: Internationally we’re discussing more walls than ever before. Do you think anything can be learned from the Berlin example?

Daniel Libeskind: I think yes, although I would say the operation was successful, but the patient is not well. I want to clarify though that Berlin is beautiful and fantastic. It has energy and it is moving forward. But there is a lurking emptiness also, that doesn’t seem like the provocative and fascinating city that draws its strength and power of its history. Maybe soon there will be an era where there’s a new sense that buildings don’t have to conform to ideology. Architecture doesn’t have to be a political exercise, it can be turned towards people based on human desires and needs.

GRAFT: What, do you think, will define the architecture of the future of Berlin: political struggle or people’s initiatives?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, I personally hope that the communal initiatives will resonate more with public authorities, because this is where the creative energy of Berlin really lies. It’s not in the bureaucracy and technocracy, it’s in the hands of interesting people.

As I mentioned earlier, the fact that people from the East were not really empowered to participate in the reconstruction of the city is becoming a problem. Why were they not part of any of these decisions? Instead, an organization like the Treuhand (Trust Agency) sold the properties to private investors. It’s bad when you disenfranchise people in a democracy, when you give them an explicit surface right, but you don’t really involve them in the discourse and hear their points of view. In the future, architecture can involve people much more in the conflict of history, of interpretation. Because this conflict is something vital, that prevents buildings from becoming a fake, redemptive idea of history, and creates a history that is fully reflective of our time. When talking about walls, the Iliad of Homer and the Trojan horse come to mind. There are many ways you can breach a wall, with a good idea for example.

[Title Image “Alexanderplatz Model” (c) Uwe Rau]