Queer Wizards and the Magic of Neurodiversity

Transgressive, liberated, powerful – wizard characters offer spaces of hope and transformation for young queer and neurodivergent readers.

My most recent book Thinking Queerly emerged from a busy semester where I was teaching courses on both medieval literature and literature for young adults (YA). My medieval students were curious about the depiction of adolescence in work by the fourteenth-century poet Chaucer, while my YA students saw all kinds of medieval themes in Harry Potter and Rainbow Rowell’s Carry On.

It made me think about how the wizard figure moved through various eras, and what it might be like to grow up as a wizard. When you can deliver a prophecy, or save the world with a spell — what are your teen years like? And how might wizards be figures of hope for young readers who don’t fit into one particular identity?

I’m queer, gender-fluid, and on the autism spectrum, so I’ve always identified with wizards because they’re both keen observers and wonderful shape-shifters. Stories about King Arthur were supposed to seduce me with the honor of knighthood — an honor that was largely constructed in the Middle Ages to paint over war crimes — but I was really drawn to Merlin and Morgan le Fay. They existed, and thought, differently from other characters. They seemed to be on their own wavelength.

“Wizards are queer in the sense of transgressing social rules, but also in the deeper sense of being liberated, unbound to a particular form or desire.”

Neurodiversity is the idea that all brains are different and equally valid. Under that umbrella, the concept of neuro-queer — popularized by autistic scholars such as Nick Walker and Melanie Yergeau — suggests that neurodivergent people can think in ways that radically reshape existing norms. Our brains are our superpowers, and wizards do the same thing. They’re queer in the sense of transgressing social rules, but also in the deeper sense of being liberated, unbound to a particular form or desire.

The Magic of Self Discovery

The really fun part of this project was discovering what I came to think of as minor wizards, both in medieval literature, and in YA adaptations that re-shaped the Middle Ages for contemporary teen audiences. You don’t have to be a grand mage to be magical. There’s the middle-class wizard in Chaucer’s Franklin’s Tale who hires out his services, and Sebile, the minor Arthurian enchantress, who clashes with Morgan over which is the most beautiful (spoiler: Morgan doesn’t care because she’s the more powerful one). In Peter Beagle’s fantasy classic The Last Unicorn, the wizard Schmendrick is incompetent but good-humored; in Terry Pratchett’s Tiffany Aching series, Tiffany sees the world in a way that might resonate with young readers on the autism spectrum.

“When wizards appear in young-adult novels, they often show us that adolescence is a kind of magic — painful, uncertain, but transformative.”

Everywhere I looked, wizards seemed to move, think, and desire in queer ways. Morgan becomes living stone to hide from Arthur’s men. Merlin, as an awkward teen, experiences social anxiety and possibly PTSD in early medieval texts like Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Life of Merlin. When wizards appear in young-adult novels, they often show us that adolescence is a kind of magic — painful, uncertain, but transformative.

Ultimately, this project showed me that the witches and wizards I’d turned to as kid were still helping young queer and neurodivergent readers to discover themselves. In that sense, ideas and cultures from the Middle Ages could still be relevant to contemporary teens, who might learn ingenuity and resiliency from characters like Gandalf (canonically nonbinary — Tolkien’s wizards are spirits), Merlin, and Morgan.

In an ableist world that wants both queer and neurodivergent people to think and behave according to restrictive norms, the wizard shows us how much power exists in being ourselves.

Learn more in this related title from De Gruyter

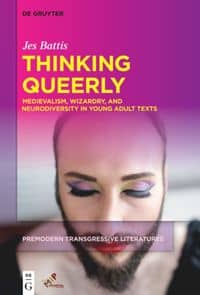

[Title Image by Sharon McCutcheon via Unsplash]