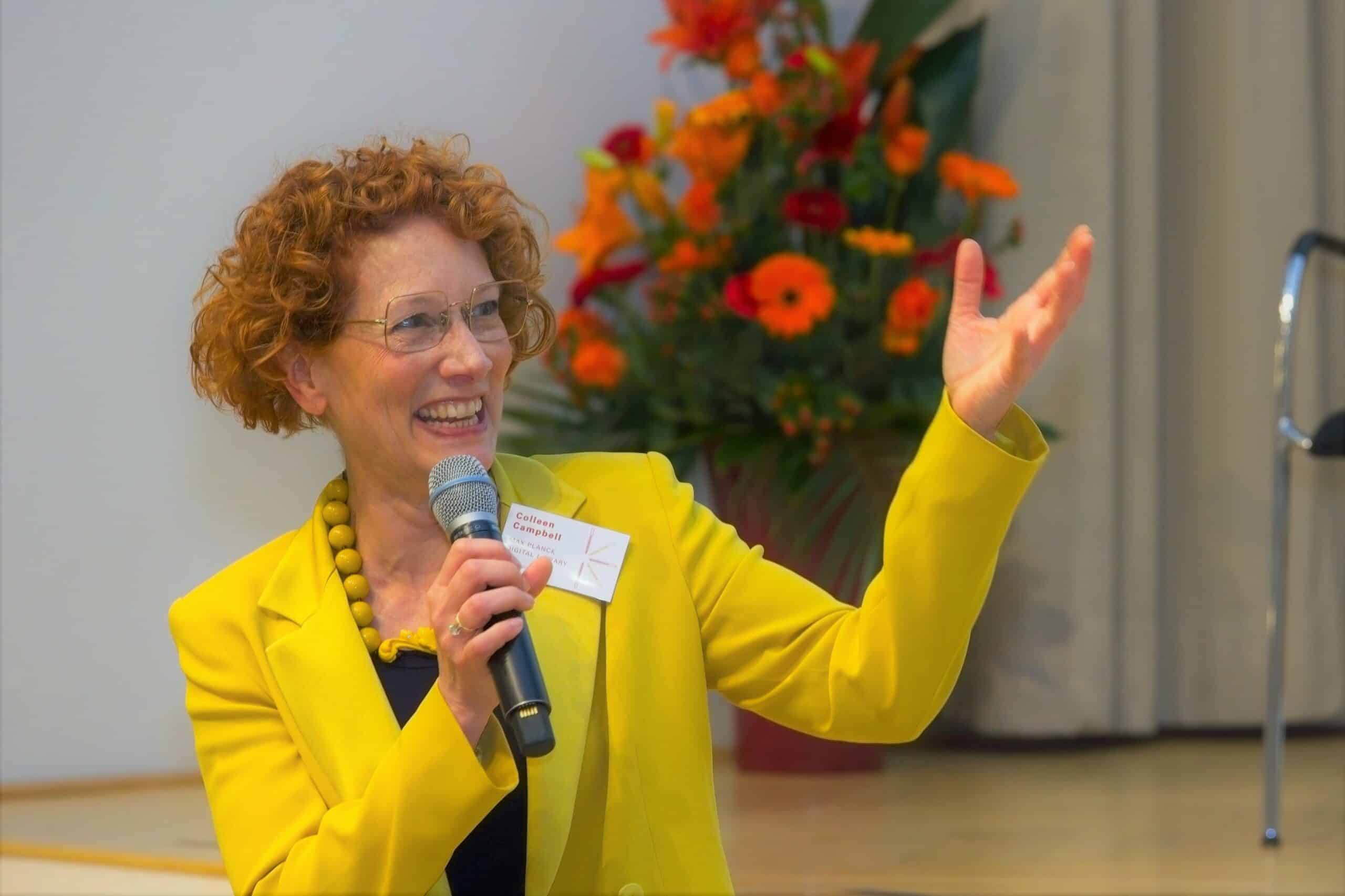

Poised For a Great Future! An Open Access Week Interview with Colleen Campbell

Our Open Access Week world tour concludes in conversation with Colleen Campbell, who emphasizes the importance of high-level reflection on the development of open access, viewing its growth as a dynamic evolutionary process rather than a simple series of experiments and events.

Did you know? Taking Libraries into the Future is also a quarterly webinar series for academic librarians. Learn more here.

Colleen Campbell leads external engagement in the open access transition at the Max Planck Digital Library (MPDL). As coordinator of the OA2020 Initiative, she focuses on capacity-building activities to empower librarians and other stakeholders with strategic insights and essential skills as they work to enable an open, sustainable and equitable scholarly publishing environment. In this post, Colleen speaks to Gold Leaf’s Linda Bennett about the continuous evolution of open access, contextualizing the highs and the lows while reminding us that the best is yet to come!

Linda Bennett: To what extent do you think OA has been successful?

Colleen Campbell: To gauge the success of open access, we must take a step back and reflect on our journey from where we began to where we are today. The remarkable growth of open access in the past decade speaks volumes about the progress we’ve achieved. In fact, Time recently recognized the surge in public access to research as one of the 13 positive changes in the world for 2023. This isn’t just a sign of progress; it represents a significant transformation.

However, we must remain grounded in reality. The landscape of scholarly communication is complex, comprising numerous interconnected components. I think that the conversation should not center on whether we’ve succeeded or not; rather, it’s about acknowledging the meaningful progress we’re making and the real transformation we are enabling. The landscape is increasingly open and the scholarly communication ecosystem is continuously evolving.

What’s propelling this change? It revolves around recognizing the distinct roles and influences that various stakeholders possess in this ecosystem. Each actor – be it researchers, funding bodies or librarians – has come to understand their capacity to effect change, the areas they can influence and those they cannot control. This understanding is critical to our success. Libraries are leveraging their investment in scholarly publishing to break down paywalls. Authors, when given the means and opportunity, overwhelmingly opt to publish their work under open Creative Commons licenses. Policymakers, like those involved with cOAlition S and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), are stepping up with mandates, while university leadership within the Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment (CoARA) is committing to reforming research assessment criteria, lowering barriers that hinder transformation.

The train has definitely left the station, and with each stakeholder embracing their own responsibility in open access. There is no turning back.

LB: What have been the greatest triumphs and challenges, from your own perspective?

CC: The greatest triumphs? Let’s kick things off with the remarkable surge in public access to research and the incredible cost efficiencies we’ve achieved through transformative open access negotiations around the globe. But what truly stands out is the potential created when the different actors – libraries, university leaders, authors, grant funders – come together. It’s driving a deeper understanding among all these players of how their individual open access strategies can work better together. This is sparking a global shift in how we approach open access with integrated strategies – investing in long-term Diamond OA, negotiating with publishers on behalf of authors, reimagining incentive structures, and so much more. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution; instead, we’re pursuing a multi-pronged approach with a singular focus: Putting the needs of scientists and scholars at the forefront.

“The biggest challenge? It’s us – our own hesitation to embrace change.”

Now, the biggest challenge? It’s us – our own hesitation to embrace change. The moment we acknowledge that transformation is happening all around us, we become more comfortable in adapting to change. We evolve. The digital revolution has ushered in a new generation of researchers who demand access to knowledge at their fingertips and who are eager to share their own discoveries freely. Open access isn’t about trying to retrofit an antiquated system to those expectations – it’s about adapting to them and restructuring our organizations to be more agile and prepared for further evolution in research dissemination.

LB: What, if any, have been the unforeseen consequences?

CC: In an evolutionary process, I do not think it is helpful to think in terms of unforeseen consequences; instead, with every step forward we take, it is natural to find fresh challenges that inspire us to think bigger and smarter. For decades, research outputs have been on the rise, fueled by consistent and increasing investments in science. Today, nearly half of all new scholarly articles are published open access under a CC BY license. That’s an incredible leap forward!

But let’s be clear: As open access grows and starts to surpass publishing under traditional subscription models, the entire landscape of research communication is evolving. Policies, academic practices and even the criteria for securing tenure are being redefined. It’s like we’re levelling up in this game!

“It’s not just a passing trend; it’s a transformation we’re actively witnessing—one that will redefine how knowledge is created, shared, and valued.”

Transformative Agreements have truly been a game-changer, tackling the financial side of OA head-on. Yes, we face challenges; reorganizing funding, budget lines, processes and workflows around OA is hard work. While some might view this as a drawback, I see it as progress because we’re finally bringing costs into the spotlight. We’re acknowledging that the financial burden of open scholarly communication should not rest on individual authors, but that institutions and funders need to recognize their financial responsibility for open dissemination of research. After all, scholarly communication is part of the research process. The library community, especially, is beginning to understand this crucial reality.

By making costs transparent, we’re not just crunching numbers – we’re uncovering opportunities for change. We’re critically examining the entire system to identify what’s fair and equitable, and we’re actively shaping the future of open access to be even better. That’s where the real power lies!

As I travel the globe connecting with the OA2020 community, one question always lingers in my mind: What does ‘fair’ truly look like? The very fact that we’re even asking this question is a monumental achievement. In the past, there was no conversation around fair or equitable pricing: The prices of subscription paywalls were utterly opaque, and institutions had no understanding of the financial weight of the open access publishing fees their authors were paying. Publishers would grant waivers and discounts to authors in lower-income regions, but that’s not what is truly needed to create a more inclusive system. No one wants handouts; they want real, transformative change.

Open access isn’t just another business model – it’s a revolution in how we think about sharing knowledge. It’s not merely about tweaking the old system; it’s about embracing something fundamentally different. Once we stop considering open access as something ‘different’ and instead see it as natural characteristic of research and the scientific process, it all clicks: This is how science was always meant to be – open, collaborative and shared!

“The remarkable growth of open access in the past decade speaks volumes about the progress we’ve achieved.”

Creating a level playing field is about integrating this perspective into our strategies. When we focus on open sharing as the natural state of science, that’s when real transformation kicks in. We start building systems and budgets that genuinely support all scholars, recognizing that different fields have unique needs. For some disciplines, journals are not just publications – they’re their core community, their peer group. Changing this mindset is the crucial first step toward levelling the playing field for both authors and readers.

Here’s the exciting part: The real value in scholarly publishing isn’t just in the act of reading – it’s in the services provided to authors. That’s where our investment should be directed. Researchers don’t just want access; they want information at their fingertips, instantly. Traditional funding streams may not align with this new reality, but let’s remember: This industry has navigated transitions before. We successfully adapted to the digital shift, and we’ll do it again with open access. The playing field isn’t quite level yet, but we’re making strides – one institution, one country, one alliance at a time.

LB: Do you think it will ever become possible for all scholarly publishing to become available via the OA model?

Colleen: I genuinely believe it’s nearly inevitable that the majority of scholarly publishing will transition to open access modes. But let’s be clear: This shift isn’t just about policies and business models; it’s about the remarkable technological advancements we’re witnessing – especially with artificial intelligence. The potential of these technologies is unlocking exciting new methods and avenues for knowledge creation and sharing. The sciences are set to thrive as they harness this innovation, and it’s certainly going to be a thrilling roller-coaster ride!

But a key part of this evolution will revolve around how we reward and incentivize scholars. Currently, metrics like publication volume and impact factors dominate, but I suspect these will eventually become relics of the past in this new landscape.

“Open access isn’t just another business model – it’s a revolution in how we think about sharing knowledge.”

Are there valuable lessons to be learned from the transitions we’ve seen in moving from print books to eBooks? Absolutely: The long-form monograph isn’t going anywhere; it still plays a vital role in the academic landscape. Different disciplines will have unique needs, and the book as an artefact will continue to hold its significance in fields where in-depth exploration and contextualization of topics is valued. Open access and new technologies offer opportunities for more powerful fruition of long form outputs.

The future of scholarly publishing is bright, and open access is the way forward. It’s not just a passing trend; it’s a transformation we’re actively witnessing—one that will redefine how knowledge is created, shared, and valued.

LB: How do you think the OA movement will progress in the next five to ten years?

CC: In the next five to ten years, one of the pivotal challenges we face is understanding how AI will be integrated into science communication. If we harness AI correctly, it can become a powerful ally for the open access movement and the scientific process. Already we see its relevance and impact on authors’ rights.

In the past decade, subscription-based publishers have thrived on two primary revenue streams: Subscriptions and the open access publishing fees of hybrid journals. But here’s where it gets mindboggling: We’re now seeing the emergence of a third revenue stream. Publishers are selling usage rights to tech companies for training large language models, generating significant revenue with minimal effort on their part.

To address this, open access negotiations with publishers are bringing the key issue of author rights to the forefront to ensure that authors are empowered to make choices on how their work is used and distributed. In the context of open access, this means CC BY.

The open access movement is redefining how we think about and engage with science communication, and the best is yet to come!

And that’s just the start! We’ll also see a robust expansion of the 360-degree strategy for open access, although it will take some time. Scholarly journals have been around for centuries, and scholars truly value them; they’re probably not going anywhere any time soon. However, as open access solidifies its place as the foundation of publishing, expect to see increased and diversified investment in scholarly communications.

New networks and innovative models – think more collective open access publishing services, more atomization of research outputs, and increasing science communication practices rooted in open science principles – will come into play. These may not replace all existing journals; instead, they’ll offer authors greater choice and flexibility. We’re moving toward a landscape where fresh avenues for sharing knowledge meet the diverse needs of all authors, breaking free from the constraints of traditional journal wrappers.

Look at the progress we have made! The open access movement is redefining how we think about and engage with science communication, and the best is yet to come.

You might also be interested in this blog series

[Title Image by akinbostanci/iStock/Getty Images]