Neuropolitics: How Looking Inside Our Brains Can Help Save Democracy

What happens when people feel unheard and vote for a demagogue? What Plato attributed to the concept of ‘Thymos’ 2,400 years ago, today finds a tangible connection in the brain. The ramifications for democratic thought are profound.

We often use the phrase, ‘out of the frying pan into the fire’. When doing so, we unwittingly cite Plato. The great Greek philosopher used the phrase to describe how ordinary people who feel left behind will sometimes vote for a demagogue. The feeling that led to this was Thymos – a term that translates as ‘spiritedness’.

It is not difficult to draw parallels between the collapse of democracy in ancient Greek city-states and similar developments in modern polities today. But we can go one step further. Now we can even identify the part of the brain that hosts ‘Thymos’. We can, so to speak, put Plato into the brain scanner. To do so, we need to draw on fMRI-scans of the brain. This is a technique that measures the blood flow to different parts of the brain. Among other things, this allows us to identify the parts of the mind associated with political thinking.

The technique might be novel, but the ambition is not. Many philosophers have drawn upon science to elucidate political philosophy. To name but a few, Thomas Hobbes drew on new developments in physiology to write Leviathan, while David Hume invoked Sir Isaac Newton’s Principia to “introduce the experimental method of reasoning into moral subjects”. In my research, I rely on fMRI-scans to do the same.

The Emergence of Neuropolitics

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in neuropolitics. Specifically, around the turn of the millennium, related studies gained momentum in the fields of politics, law, and economics. The emerging interdisciplinary field of political neuroscience (or neuropolitics) focuses on understanding the neural mechanisms underlying political information processing and decision-making.

To quote Haas, Warren, & Lauf (2020): “While the field is still relatively new, this work has begun to improve our understanding of how people engage in motivated reasoning about political candidates and elected officials and the extent to which these processes may be automatic versus relatively more controlled”.

“The big idea of neuropolitics is that we can identify the parts of the brain that thinkers like Plato hypothesised to exist.”

The big idea of neuropolitics is that we can identify the parts of the brain that thinkers like Plato hypothesised to exist. Accordingly, my research has not invented a new field of science; rather, it has applied new techniques. Sort of like Thomas Hobbes: he did not invent the mechanistic view of the world; he merely applied it.

The Birthplace of Thymos

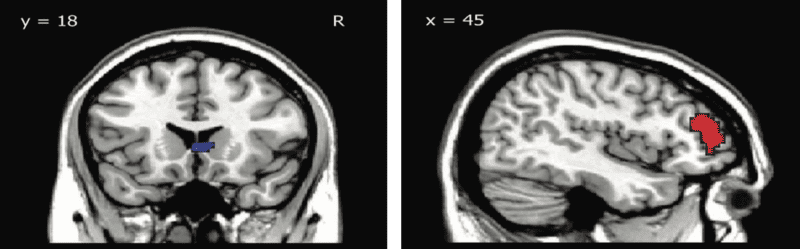

So, what do we know? One of the findings of the emerging empirical research into neuropolitics is that our behaviour follows a distinct pattern, with different parts of the brain being activated depending on our politics. Notably, it has been shown that those who are most likely to engage in violent protest show high activation of a part of the brain called the amygdala, which is generally associated with fear and anger. It has sometimes – slightly inaccurately – been called the ‘fight and flight’ centre of the brain.

“Neuroscience allows us to see what goes on in our brains when we feel unheard, when we feel left behind, and when we vote for demagogues.”

With this finding, modern neuroscience essentially indicates that our brains work in ways analogous to the model outlined 2,400 years ago in Plato’s Republic. To put it rather bluntly, neuroscience allows us to see what goes on in our brains when we feel unheard, when we feel left behind, and when we vote for demagogues. But, as we shall see, there might also be positive findings coming out of this.

The left scan in the image above shows the brain of a person with an activated amygdala (marked in blue). On the right, look at another fMRI-scan of the same brain when exposed to a simple political argument about economic policy. This time, another part of the brain lights up (marked in red), specifically the dorsolateral frontal cortex – a region associated with listening, speaking, and reasoning. This indicates that the same person, who previously showed reactionary Thymos in the amygdala, is now capable of engaging in rational argumentation.

Tapping Into Our Full Potential

If we tap into the full spectrum of our neurological endowments, we can solve problems and learn from each other. Engaging our brains in this way not only addresses societal issues but also, as research indicates, makes us less likely to develop degenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. What’s not to like here? However, if we choose a different path and revert to fear- and anger-driven behaviour, we begin our descent down the evolutionary ladder. We have a choice to make.

Today we can – for better or worse – peer into our minds and literally see what we think. This realization aligns with the dreams of materialist philosophers like Hobbes and Hume.

“if we choose a different path and revert to fear- and anger-driven behaviour, we begin our descent down the evolutionary ladder.”

This development clearly has profound implications for democratic thinking and, more broadly, for political science. Hitherto, there have been scattered attempts by political scientists to use brain imaging, and some attempts by biologists to apply their knowledge to political subjects. They allow us to adopt a neuroscience perspective on political philosophy and classics. In other words, fMRI scans can be applied in the same way that Hume used Newtonian physics.

Neuropolitics can teach us many things. By understanding the world of neurons, neurotransmitters, and neuroanatomy, we can heal the body. In the same way, understanding the biology of the brain can help us fight the pathologies of social and democratic decay. In essence, neuropolitics can help us heal societies and contribute to preventing the death of democracy.

Learn more in this related title from De Gruyter

[Title by nopparit/E+/Getty Images]