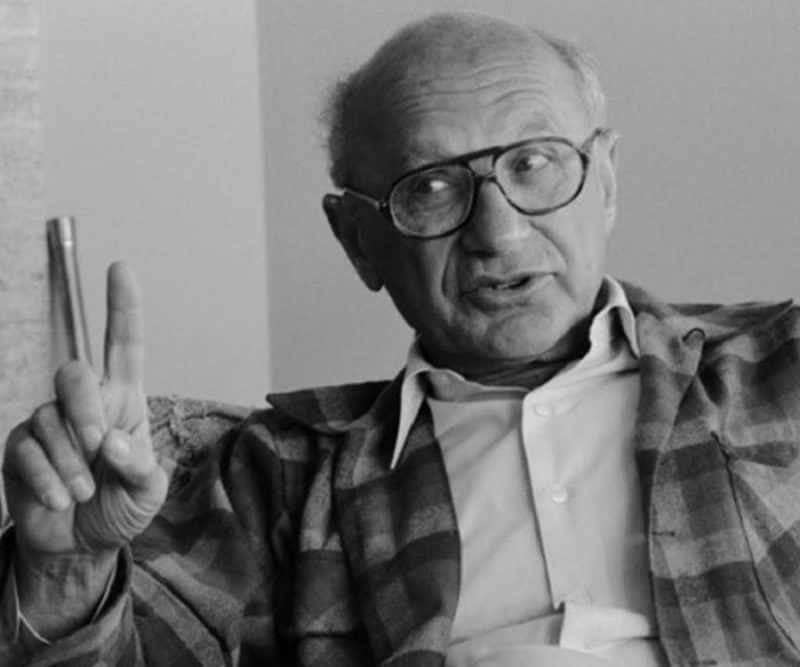

Milton Friedman: There is No Such Thing as a Free Lunch

Nobel prize-winning economist Milton Friedman is best-known for his unwavering belief in free enterprise and opposition to state intervention in business and trade. He passed away in San Francisco at the age of 94 on November 16, 2006.

This article is an excerpt from Murray Polner, American Jewish Biographies, Lakeville Press, 1982. It is one of the over 8.5 Million biographical articles included in the World Biographical Information System Online Database, a subscription-based digital collection of biographies from around the world.

Milton Friedman was born in Brooklyn and reared in Rahway, New Jersey, by his Ruthenian (then part of Austria-Hungary) immigrant parents, Jeno Saul, a merchant, and Sarah Ethel (Landau) Friedman.

As a high school student, he displayed a facility for mathematics and won a scholarship to Rutgers University, where he received a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1932. While there, he was forced to take a two-year ROTC course, and he has since said it gave him a permanent distaste for compulsory military service.

After receiving an M.A. degree in 1933 from the University of Chicago, Friedman held several research and teaching jobs before earning a Ph.D. from Columbia in 1946. From 1935 t0 1937 he was associate economist with the National Resources Committee in Washington, and from 1937 to 1945 he was on the research staff of the National Bureau for Economic Research in New York.

He was also director of research and statistics for the war research division at Columbia from 1943 to 1945 and was a visiting professor of economics at the University of Wisconsin in 1940 to 1941 and principal economist of the tax research division of the Department of Treasury from 1941 to 1943.

After teaching for one year at the University of Minnesota from 1945 to 1946, Friedman joined the faculty of the University of Chicago, and in 1962 he became Paul Snowden Russel Distinguished Service Professor of Economics, a position he held until 1977, when he joined the Hoover Institution at Stanford University as a research fellow.

Participation in political decisions

When Menachem Begin was elected prime minister of Israel in May 1977, he invited Friedman, the recipient of the Nobel prize in Economics in 1976, to visit Israel and suggest remedies for Israel’s soaring inflationary spiral.

The Begin government’s respect for the University of Chicago advocate of the free market and his lifelong opposition to nearly all sorts of government intervention was matched by the Nobel judges when they honored him “for his achievements in the fields of consumption analyses, monetary history and theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy.”

A Libertarian Anarchist?

“For Friedman, personal liberty is the supreme good – in business affairs, politics and social relations.”

Dubbed a “pure intellectual” by admirers and critics, Friedman has also been described by his son David, also an economist, as a “libertarian anarchist,” whose fundamental outlook is simple and uncluttered: personal liberty is the supreme good – in business affairs, politics and social relations.

Thus, he has condemned the New York Stock Exchange as a brokers’ commission-fixing monopoly. He favors the school voucher plan, whereby parents can select any school for their child. He also believes that the individual and not the government should decide if smoking is harmful. And he is against conscription and favors an all-volunteer military force because the draft is an unacceptable form of compulsion.

Free to choose

He is the author of a number of books and pamphlets, among them Roofs of Ceilings, co-authored with George Stigler (Chacago, 1946), which counsels against postwar rent controls and advances the idea that the free market would produce far more housing units than the federal government; Capitalism and Freedom (New York, 1962), which reflects the Friedman thesis – similar to 19th-century liberal philosophies – of free trade abroad and laissez-faire at home, with a minimum of federal involvement; There is No Such Thing as a Free Lunch (La Salle; III., 1975); and the best-selling Free to Choose, written with his wife Rose (New York, 1980) in which the authors contend that only when individuals are permitted to make their own economic decisions will other problems – economic, environmental, social and so on – be solved.

In 1980 his television program Free to Choose, a 10-part series produced for Public Broadcasting System, proved to be extremely popular. A typical program was entitled “The Tyranny of Control.” In it he argued in favor of a constitutional amendment prohibiting Congress from imposing any tax on imports or permitting subsidies for exports.

The mid-nineteenth-century British policy of free trade was – to him – ideal insofar as free trade and free markets flourished. By contrast, he says, protectionism has always resulted in stagnation economies and acted as a deterrent to the development of industrialization. Government subsidies, he says over and over again, are “always backward-looking, protecting the industries that already exist.”