In the Eye of the Storm: U.S. Diplomat Hugh Gibson and the ‘Spanish Flu’

In 1918, when both World War I and the ‘Spanish flu’ raged in Europe, the American diplomat Hugh S. Gibson was sent to Paris. Today, his personal records offer us rare insights into a time between disease and diplomacy.

‘Pandemic’ is a word on everyone’s mind in 2020 as a storm named Covid-19 wreaks havoc around the world. A personal look at one man’s walk through a past pandemic, the storm called ‘Spanish Flu,’ offers both historical perspective and inspiration to cope with the current challenges.

Europe had been at war for four years when the merciless second wave of the ‘Spanish Flu’ hit in autumn 1918. During the lull between the first and second waves, a dashing young American diplomat – Hugh S. Gibson – was posted as Secretary to the Embassy in Paris.

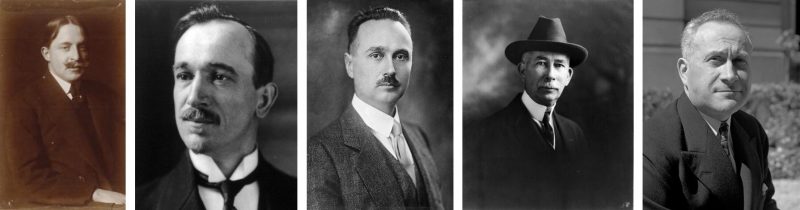

Gibson served as diplomatic adviser to General John Pershing, as well as G2 Intelligence Generals Dennis Nolan and Ralph Van Deman. He also was tasked to straighten out some of the more unfortunate impressions created by various independent agents of George Creel’s Committee for Public Information. By summer 1918, Gibson was additionally designated as the official liaison between the US and both the Czech and Polish national committees.

Upon the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Gibson refocused his efforts from military/intelligence to humanitarian affairs as the diplomatic advisor of Herbert Hoover’s American Relief Administration. As such, he travelled east and assessed the situation facing Austrians, Italians, Hungarians, and Yugoslavians from political and economic, as well as humanitarian, perspectives in January 1919.

Gibson’s adventures are recorded in An American in Europe at War and Peace, edited by Jochen Böhler and me. Interspersed throughout this amazing record are references to the devastating second wave of the Spanish flu, which are extracted and presented here, complete with photographs and notes.

Between Disease and Diplomacy

Paris. Saturday, October 5, 1918:

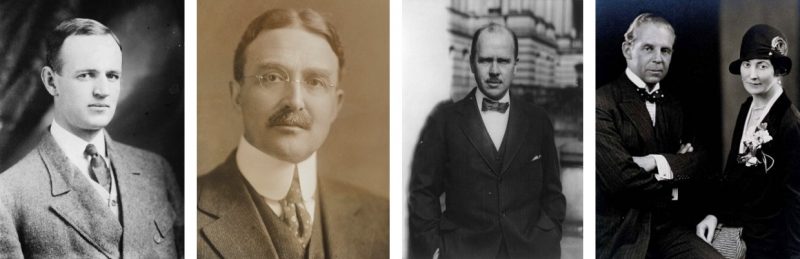

Clarence Gagnon (1881-1949) was a Canadian painter whom Gibson had befriended before World War I began.

“After lunch went over for Clarence [Gagnon] and spent a solid hour getting a taxi to take Clarence to the hospital. … He seemed to be just on the verge of delirium and not at all sure either in his thoughts or movements. … Dr. Moore received us at the hospital and after one look at Clarence and feeling his pulse, called for a chair and had him carried upstairs. … When he finally came downstairs he looked very grave and said that Clarence had an unusually bad case of flu with bronchial pneumonia to aggravate it.”

Paris. Saturday, October 5, 1918:

“A little after noon a story came thru from Switzerland to say that Germany had made an appeal to the President at the instigation of Turkey for a general armistice with a view to discussion of terms. The censorship had stopped it and forbidden publication but later in the afternoon the news was confirmed and the govt. decided to release it for publication tomorrow morning. … I telephoned the news to the Ambassador and put in a call for GHQ but did not get thru. … Feeling very groggy with the flu so took a hot bath and got early to bed after setting back the clock for the end of summer time.”

On October 3, 1918, Max von Baden was appointed as Chancellor of the German Reichstag. Bypassing the French and British governments, von Baden requested an armistice via Switzerland.

It is notable that Gibson received this news personally, and then informed Ambassador William Sharp. It is also notable that this entry occurs on the same day that Gibson cared for Gagnon. Never one to shy away from helping a friend, Gibson was ill himself by evening.

Paris. Tuesday, October 22, 1918:

Edvard Beneš (1884-1948) was Secretary of the Czechoslovak National Council in Paris 1916-1918. He supplied Gibson with statistics, plans and drafts of materials to be presented to the Peace Commission.

John Batterson Stetson, Jr. (1884-1952), son of the famous western hat maker, was on active military duty until 1920, which brought him to the US Embassy in Paris. He and Gibson not only worked together but shared a flat.

“With the morning papers came the memo from Benes. I settled down to thump out my own telegrams, only to learn that my typewriter would not work as Stetson had knocked it over last night and put it on the fritz. Reaching the chancery I found that my stenographer had chosen this time to have the flu.”

By this day in 1918, Gibson’s morning papers held stories like the German suspension of submarine warfare, the successful conclusion of the Second Battle of Belgium, and of course updates on the Spanish flu epidemic.

Paris. Saturday, October 26, 1918:

“Woke up groggy with the flu but staggered down to the chancery to see whether I would be needed in connection with Col. House and the other visiting firemen.”

Edward Mandell House (1858 –1938) was top advisor to President Wilson and played a major role in shaping wartime diplomacy. Although generally referred by as the “Colonel,” he never performed military service, nor did he hold public office.

After four years of war, a seismic shift was redefining the political and social order. A mad diplomatic hustle was underway to arrange acceptable terms for peace. For Gibson, working at the very center of all this, work only intensified. There was no time to “self-quarantine” as we would say today.

On March 26, 1919, as he awaited his next appointment, Gibson penned a tribute to Edward Mandell House:

“Ode to Colonel House

Wholly unquotable

Always ungoatable

Secretly notable

Silence’s Spouse.

Darkly inscrutable

Quite irrefutable

Nobly immutable

Edward M. House”

Paris. Sunday, October 27, 1918:

Štefan Osuský (1889-1973) was a Slovak lawyer, diplomat and academician. Between 1917 and 1918, he was the director of a Czecho-Slovak news agency in Geneva which brought him into contact with the American Legation in Switzerland.

“Woke up with a good start of flu so took it easy – went down to the chancery before lunch and found little to do.

There was a telegram from Osuský (sent through the Minister at Berne) to say that Staněk and the other Czechs had arrived from Vienna and were anxious to see Benes. I wrote a note to Strimpl giving him the text of the message and then went my way.”

Gibson was the natural person to receive this telegram from Geneva, where both domestic and exiled Czech leaders gathered. The roster included: Kramář, Beneš, Osuský, Klofáč, and Habrman. At noon the next day, independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire was declared. October 28, 1918 became Czechoslovakian Independence Day.

Paris. Monday, October 28, 1918:

“A long afternoon devoted to doing my own typing in the absence of Miss Bennet who took one look at the large supply of work I had set out for her and then went home with a temperature. And after getting everything arranged it developed that the courier could not go till tomorrow night as the day trains have been taken of ‘because of the flu.’”

The Spanish flu was more infectious, caused harsher symptoms faster, and was even more deadly than the current pandemic. This was particularly true because it targeted young persons in their prime rather than compromised persons as does Covid-19.

While we are inundated by news flashes and sound bites, Gibson and all the world’s leaders had to wait hours or days for information, responses or orders. Telephone service was rudimentary. Telegrams were more reliable but still took time and/or passed through many hands. Because security was paramount, couriers were often employed to physically deliver sensitive information to specific persons.

Part of Gibson’s job in Paris was managing diplomatic, military and intelligence information. The wartime courier service Silver Greyhounds was established by General Pershing in March 1918 and utilized by Gibson on many occasions, including this one. After the Armistice of November 11, 1918 the Silver Greyhounds were incorporated into the State Department.

Hospital trains were designed to help meet the need of caring for injured and ill servicemen. On certain days, like this one, other train traffic (and sometime the train cars themselves) were commandeered to evacuate persons to safe zones.

Paris. Saturday, November 2, 1918:

Walter Lippmann (1889-1974), American writer and political commentator, served in the intelligence section of the American Expeditionary Force headquarters in France.

“A morning of misery with the flu. Had about made up my mind to go home to bed when Walter Lippmann telephoned from Col. House to say that there were some things they wanted me to do and asked me to stay on during the afternoon.”

Paris. Sunday, November 3, 1918:

“Got up late and spent most of the day fighting off the flu. Martin Egan came in a little after noon and stayed on till just before dinner… [H]e does not go in much for the idea of a League of Nations, but that if it must be we should have a National League and a Bush League which can contribute members as they become worthy.”

Martin Egan (1872-1938) was an American newspaperman who worked with JP Morgan and Co 1910 and 1938. He interrupted this tenure to serve as one of Pershing’s top civilian advisers for public relations and propaganda during 1918.

By the end of October 1918, Egan had dubbed Gibson as “Yougo Gibson,” a nod to his assignment as Liaison to both the Polish and Czech National Committees.

Armistice Day, Paris. Monday, November 11, 1918:

“The armistice was signed at five this morning and went into effect at 11. … Flags came blossoming out on all houses and groups of people went parading the streets singing and cheering for Clemenceau and anything else that occurred to them at the moment.”

At the height of the devastating second wave of the Spanish flu came Armistice Day. The Armistice went into effect at the poetic moment of the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918. However, thousands of men died between when the deal was signed at 5 am and the effective time of 11 am. The American Expeditionary Forces on the Western Front alone lost more than 3,500 men. It is estimated that as many as 11,000 men died that morning on the battle fields or from the flu.

Paris. Wednesday, November 13, 1918:

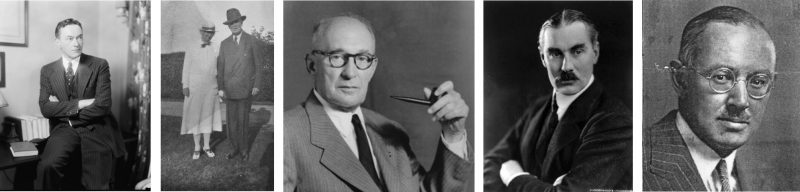

Arthur Wilson Page (1883-1960) was the son of Walter Hines Page, US Ambassador to the UK 1913-1918 and later became known as the founder of “public relations”.

“Arthur Page laid up with a touch of flu and spent the day in bed. He has sent his resignation to James and is ready to go home in the course of the next few weeks.”

Paris. Monday, November 18, 1918:

“At noon went over to see Colonel House who said the Department had approved the idea of establishing an intelligence service in Central Europe. He wants to suggest now that Hoover and I lay the basis for the system and that I remain at the end of the trip at HQ in Vienna to oversee the work of the various agents sent in to gather information. He asked me to talk the matter over with Joe Grew who is laid up in bed with the flu and draw a cable for him to sign. […] Went down to the Ritz to see Joe and found him groggy with flu. He agreed with enthusiasm to the idea of my handling the other end of the intelligence and we drew up a telegram for the Colonel.”

Joseph Grew (1880-1965) was an American diplomat who was acting chief of the State Department Division of Western European Affairs 1917-1919 and secretary of the American Peace Commission in Paris 1919-1920.

When the US entered WWI in 1917, the Allies warned the AEF that protection against sabotage, subversion and enemy spying were critical. The Corps of Intelligence Police was born in January 1918, commanded by Gen. Nolan, who worked very hard to recruit Gibson into their ranks. Although he never donned a uniform, Gibson remained involved in the intelligence world.

Paris. Tuesday, November 19, 1918:

“Walter [Lippmann] came home to lunch with me. Arthur [Page] was up for lunch in the dining room. Merz was discharged cured after lunch and Walter took his place to get cured of an incipient case of flu.”

Charles Merz (1893-1977) was an American journalist. During the war, Merz worked in military intelligence, bringing him into Gibson’s sphere of influence.

During the devastating second wave of the Spanish flu, Merz fell ill and was hospitalized in November. By the time he was well enough to be discharged, Lippmann was ill enough to be admitted. And so the flu spread.

Paris. Sunday, December 1, 1918:

“I got up this morning to learn the sad news that Willard Straight had died in the night of pneumonia. He had a long pull but even his magnificent strength was not enough to bring him through.”

Willard D. Straight (1880-1918) was an American banker, publisher and diplomat who joined the AEF in 1917. He received a Distinguished Service Medal in July 1918, was desperately ill with the flu by Armistice Day, and died on December 1, 1918.

Paris. Monday, December 9, 1918:

“This morning we went up to the house all filled up with ideas that we were on the home stretch and that we would be tucked away under its roof by nightfall. Instead we found that practically the entire troop of workmen had deserted, that the expensive housekeep had chosen this moment to have the flu and that even the house agent who had undertaken to see that things were ready had taken to his bed with the same ailment. … I felt like the Emperor of Germany with my Empire crumbling over my head.”

After the Armistice of November 11, Gibson was reassigned to Herbert Hoover and the Food Administration. Although living and working space was at a premium, Gibson secured a large house on Rue de Lubeck and undertook the task of remodeling it to their needs and setting up household. The American Relief Administration quickly became the most effective relief organization in history.

Paris. Friday, December 13, 1918:

Dr. Alonzo Englebert Taylor (1871-1949) was an American professor of physiologic chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania and served on the War Trade Board 1917-1919. He accompanied Gibson on an investigative trip throughout Eastern Europe as the food expert.

Hugh Robert Wilson (1885-1946) was an American diplomat, posted as Secretary of the US Legation in Bern, Switzerland, first stop on Gibson’s trip.

“Dr. Taylor back from Berne with the news that Hugh Wilson is seriously ill with flu. I do hope that nothing will happen to him as he is the sort we cannot afford to do without at this time.”

This tiny entry from Gibson’s diary introduces two important figures – Dr. Alonzo Englebert Taylor and Hugh Robert Wilson – and demonstrates yet again the severe nature of the Spanish flu.

Paris. Friday, February 21, 1919:

“Another Mr. Micawber day which I am finishing up in bed trying to decide whether I have the gumption to get up or whether I shall lie me down and enjoy a little grippe [flu]. If there were more things which had to be done at once I should undoubtedly decide to stay on my feet, but for the next few days I can see nothing to do but wait for something to turn up.”

Wilkins Micawber was a character in David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (1850). This optimistic clerk had the belief that “something would turn up.”

Gibson returned to Paris from his adventures in Eastern Europe on February 1, 1919, “more dead than alive, but glad it’s no worse.” During the twenty intervening days, he kept busy while waiting for word of his next diplomatic assignment. There was a general assumption that he would be appointed as Minister to Czechoslovakia – that is, if/when the US Congress approved the funding of new legations to Prague and Warsaw. Meanwhile, like Micawber, Gibson prowled around the halls of power in Paris.

Gibson continued to meet with Hoover and Lewis Strauss. At 23, Strauss volunteered to serve without pay as Hoover assistant and made himself invaluable to the ARA. As a Jewish American, he was also helpful in promoting unbiased relief in Poland, where Jewish communities struggled. Later he again worked with Hoover and Gibson to bring relief to suffering Europeans when war returned in 1939. In 1947, President Truman appointed Strauss as one of the first five Commissioners of the Atomic Energy Commission. Strauss advocated for the use of atomic energy for multiple purposes – and remained a good friend of Gibson’s for the rest of his life.

Paris. Sunday, March 16, 1919:

Robert Woods Bliss (1875-1962) was an American diplomat, well known as an art collector, philanthropist, and co-founder of the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. In 1918-1919, Bliss was the Counselor of the Embassy in Paris.

“I lunched with the Bliss’s – just the two of them and had a really good time. They have both been laid up most of the winter with touches of the flu but are now on the upgrade.”

During their time in Paris, “Bob” and Mildred Bliss actively supported Allied troops in France by donating 23 ambulances to the American Field Ambulance Service and collected art. Later, they renovated their Washington, DC home, Dumbarton Oaks, it to display their art and develop a research library. Dumbarton Oaks hosted a conference in 1944, the outcome of which was the charter for the United Nations, which was adopted in San Francisco in 1945.

Paris. Friday, April 4, 1919:

“The President [Woodrow Wilson] is laid up with a cold today and people seem to be worrying for fear it will turn into flu. It would be a calamity to have him incapacitated now with so many vitally important things that only he can decide. It gives me the shivers to think of it.”

The thought of President Wilson having the flu gave the whole world the shivers! As it turned out, of course, Wilson did indeed have a debilitating case of the flu.

Gibson’s source of information was Rear Admiral Cary Travers Grayson with whom he had dined the evening before. Grayson met Woodrow Wilson shortly after his inauguration in March 1913. The two became close friends, and Grayson remained at Wilson’s side until his death in 1924.

Wilson came down with a particularly virulent case of the flu with a high fever and violent fits of coughing that made breathing almost impossible. At the beginning of the illness, about the time he talked to Gibson, Grayson even considered poison as a diagnosis. Soon enough, the truth became obvious.

By the end of April, Grayson wrote: “These past two weeks have certain been strenuous days for me. The President was suddenly taken violently sick with influenza at a time when the whole of civilization seemed to be in the balance.” Wilson had been so violently ill from the flu that his health was permanently compromised. In October 1919 he suffered a stroke, which left him effectively incapacitated for the rest of his term.

The Treaty of Versailles, League of Nations and other negotiated treaties he had championed failed to pass Senate ratification in 1920. Wilson finished his term in office in virtual seclusion. The US turned inward, and Europe floundered to recover before plunging into war once more in 1939. Having done its damage, the misnamed Spanish flu petered out in 1920, taking its place as one of the worst pandemics in history.

Learn more in this related title from De Gruyter

[Title Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain]