How Universities Can Outlast the Covid-19 Pandemic

In times of uncertainty, universities and faculty members must react with careful planning and future-proofing. In short, now is not the time for magical thinking.

This essay is part of the series “The New Normal: Perspectives on the Impact of Covid-19 on Academia”.

In many countries around the world, people are still having difficulties coming to terms with the realities of the COVID-19 crisis threat. This is most obvious in countries such as the USA, where poor leadership has resulted in mixed messages being given to citizens about how serious the pandemic is and to what extent they should take precautions. The USA has seen protests challenging taking precautionary action against contracting coronavirus. Even such simple actions as wearing masks when out in public have been challenged by libertarians and ‘sovereign citizens’. In the Northern Hemisphere, many universities are beginning to open their doors to students after the summer break – and almost immediately realizing that this is unworkable, as infections soar among the student body.

But even in countries like Australia, where for the most part governments have acted decisively and quickly and there has been little push-back against lockdown restrictions on the part of citizens, it is difficult for many people to understand the continuing threat they face from the virus.

After six months of battling the spread in Australia and doing well to control it, we have seen a major resurgence in Melbourne, our second largest city, due to complacency and lack of care, with lockdown re-introduced weeks after the first restrictions had been lifted. European countries have opened up their borders to travellers and tourists for the summer holidays and as a result, and unsurprisingly, have seen surges in infections. As these events have demonstrated, even in regions where the initial spread of contagion has been well controlled, a sense of safety has led to loss of control.

Uncertain Times

Given this broader sociocultural context, where does the future lie for universities? Having observed the ways that the COVID-19 crisis has been dealt with across the world over the past six months, it seems clear that little end to the pandemic is in sight, and that the only certainty is uncertainty. We cannot rely on an effective vaccine to be developed, tested and delivered globally in the near future. Citizens of wealthy countries – including academics and university leaders – have great difficulty coming to terms with these kinds of uncertainties, because they have become accustomed to investing their faith in scientific imaginaries of progress – but in this situation, there is little choice.

“Now is not the time for magical thinking.”

Protecting the health of every member of the university – from cleaning and grounds staff to university leaders as well as all students – must be the priority. Now is not the time for magical thinking. We must face the reality of the pandemic and acknowledge that there is a long way to go until we might start to feel a sense of certainty again.

Therefore, universities and faculty members need to arrive at a new way of conceptualising risk and uncertainty in this new COVID-19 era. This will mean planning for all kinds of uncertain scenarios. It will mean not moving too early to ‘open up’ classrooms and lecture theatres, however much this is desired by academics and their students as well as university leaders.

Online First

The ‘new normal’ means coming to terms with and planning for uncertainty as best we can, with all sorts of back-up options in place. It means making plans that will always be contingent on what is happening with the pandemic and therefore engaging in ‘future-proofing’. This means that teaching, conferences and library facilities must be planned as ‘online first’, with options available to move to face-to-face if possible and safe, but only until then. We must develop better ways of engaging online with each other – people are already experimenting and finding solutions, and this should continue. We should learn from those lecturers who have offered online teaching for years and have developed effective and engaging strategies.

Those of us who have traditionally used in-person social research methods will need to quickly become skilled in other methods (see Doing Fieldwork in a Pandemic for many suggestions for ways to do this). We need to become skilled in delivering presentations in an online format and working out the best ways to conduct online discussions. Moving online for seminars and conference presentations has already meant that far more people can access the content, either synchronously or (if the presentation is recorded), asynchronously. We need to become better at formatting and delivering webinars and making them available. One approach my Vitalities Lab team is experimenting with is making short-form pre-recorded webinars available on our customised YouTube channel as open access resources.

In Summary

In responding to the pandemic, those who remain inflexible or tethered to traditional ways of working – whether that’s teaching, collaborating, researching or administering will pay a heavy price. It’s only by accepting uncertainty and making careful contingency plans that we will minimise the impact of the virus now – and into the future.

We recommend this related collection of think pieces

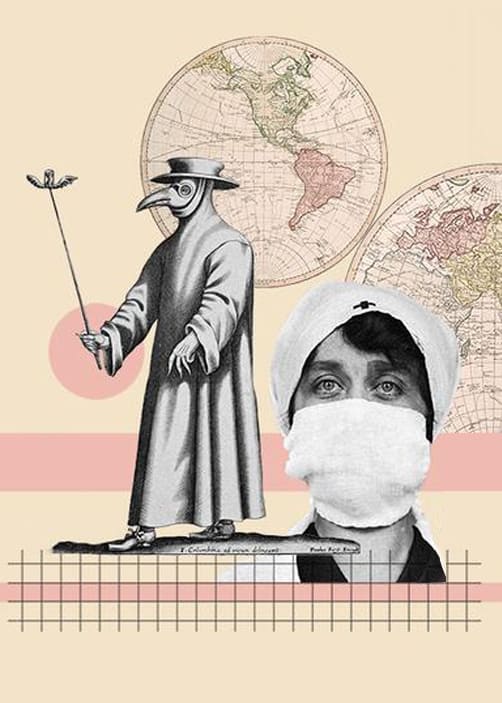

[Title Image via Getty Images]