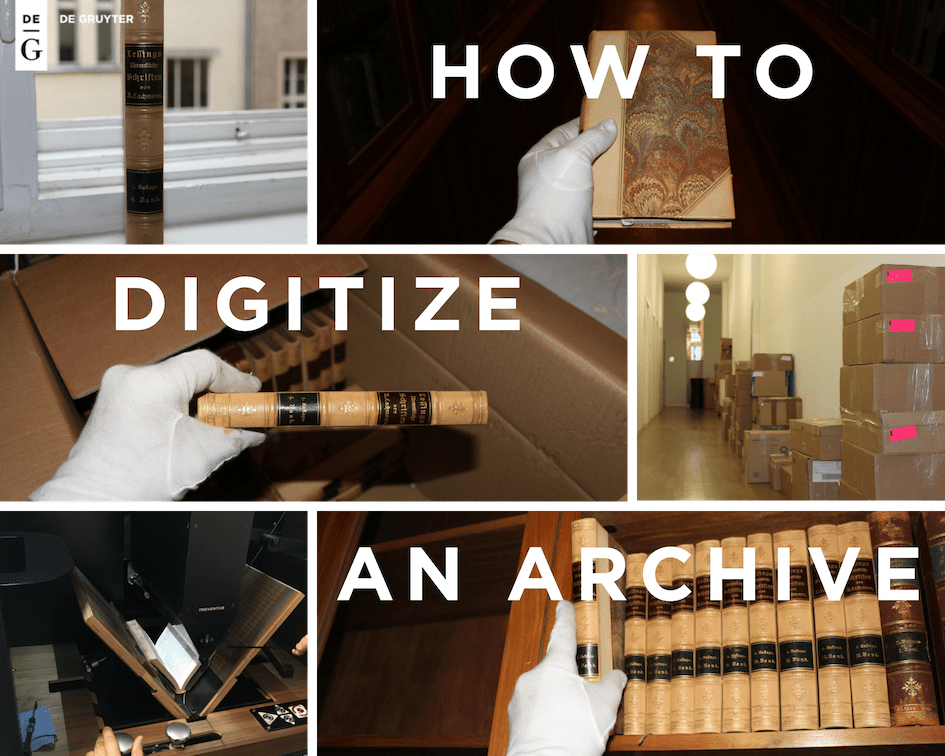

How to Digitise an Archive

Whether you’re a publisher or library, you almost certainly have hundreds, if not thousands, of historic titles that are hugely valuable to the global research community. Serious academics will climb mountains to get hold of the last remaining copy of an old title that can further their research. But if they could access that same text in minutes, imagine the speed at which their ideas could advance.

Digitising an archive to make older works available online sounds easy, but the reality of finding, transporting, scanning, refining, and organising large collections of historical publications is anything but. Project lead at digitisation specialists Datagroup, Radu Iuliu Kiritescu, explains that the road to delivering a digital archive is full of surprises:

“Sometimes we’re working with titles hundreds of years old, many of which have been sitting on shelves for decades, so we’re never entirely sure what we’re going to find when we open them.”

“Sometimes we’re working with titles hundreds of years old, many of which have been sitting on shelves for decades, so we’re never entirely sure what we’re going to find when we open them. We came across a book recently that had never been opened and when we looked more closely, we realised the pages hadn’t been cut, so we had to carefully, painstakingly separate each of the pages one by one.”

In 2016, De Gruyter embarked on digitising its entire back catalogue extending back to 1749. The collection includes works from authors such as Friedrich Schleiermacher, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Ludwig Tieck and the Brothers Grimm, to name just a few. The publisher’s aim: to provide the global research community with immediate access to 50,000 titles, published over 260 years, by the end of 2019.

If it’s going to succeed, an initiative of this scale can’t be undertaken alone. De Gruyter has been collaborating closely with institutions and libraries to fill important gaps in content and is working with digitisation partner Datagroup to ensure that these cultural artefacts are handled with the utmost care and returned home safely. Now, half way to its goal of making the full content and bibliographic data for tens of thousands of titles easily accessible, De Gruyter has divided its collection into a Frontlist (2016-18); a Backlist (2014-2000); and an Archive (1999-1759). For anyone thinking of embarking on a similar challenge, here are some of the publisher’s best pieces of advice.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

1. Don’t go it alone

One of the biggest (and most surprising) challenges of digitising any archive is identifying and finding original copies of back-catalogue titles – especially when those back catalogues extend to hundreds of years. As part of the De Gruyter Book Archive (DGBA) project, the publisher has discovered thousands more titles than it originally realised it had and hopes this will have an even bigger impact on future research than previously thought. The apparently simple task of identifying every title you have published is very far from simple in reality. The physical book archive in De Gruyter’s Berlin office only represents a fraction of everything it has published over its 260-year history. Realising early on that there was no complete list of all its published titles, the first challenge was to find out how many, and exactly which, titles would be involved in the project. This was before even thinking about how to get a hold of all the physical copies.

Collaboration with other libraries, both national and international, has been crucial to the project’s success so far. In addition to the Berlin State Library, De Gruyter has worked closely with other organisations (including: Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften [BBAW]; Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin; and Institut für Bibliotheks und Informationswissenschaft [IBI]), and has relied heavily on platforms such as the Karlsruhe Virtual Catalog to identify missing titles and fill gaps in its archive.

2. Handle with care: transporting and scanning rare historic works

The importance of collaborating with libraries to deliver the fullest possible archive can’t be overestimated. But with these partnerships comes great responsibility. De Gruyter has the support of Berlin State Library who is providing access and temporary loan facilities for over 200 titles. In return for the loan of many rare (and in some cases unique) cultural artifacts, Berlin State and other libraries working with the publisher have issued stringent insurance criteria. Adhering to the smallest of these details is crucial to building trust and delivering a high-quality digital archive.

Transporting some back-catalogue titles is the equivalent of moving expensive works of art, so everything from the temperature and humidity of storage space, to strict handling guidelines, must be followed to the letter by your digitisation partner. Having utmost trust in such a partner to operate on your behalf is also crucial, so you should develop rigorous criteria for your selection process.

Not all libraries will allow you to remove titles offsite or out of the country, so you need to anticipate having to start your search for some publications again. Other libraries expect a personal service for the transportation and return of rare titles, so you should plan for additional expenses to cover this. De Gruyter has talked about its meticulous planning and project management of the archive digitisation process, to ensure that titles on loan from libraries are prioritised for scanning and that all loan periods are honoured.

Once a publication has arrived at the scanning facility, it’s crucial that its delicate handling continues. Titles in the De Gruyter Book Archive project have been separated into ‘non-destructive’ and ‘destructive’ scanning, depending on the age and rarity of the book. DGBA partner Datagroup uses the Scan Robot SR301 which is able to carefully scan non-destructive titles at the rate of 600 pages per hour and destructive titles three times faster, at 1500 pages per hour.

3. Allow plenty of time (and even more patience)

However long you estimate your digital archive project taking, you should always add a sizeable amount of contingency time. This is a process that just can’t be rushed. You need to allow for the location of every title; the sometimes-lengthy loan negotiations with libraries; recruitment of the right digital partner; as well as the collection, scanning and return of titles. Then there’s the not so small matter of inevitable delays. (And that’s before you’ve even factored in time to fill gaps in bibliographic data and make your online content as discoverable as possible).

Project lead at DataGroup, Radu Iuliu Kiritescu, estimates an average of six weeks to collect, transport, scan and return a book. So, a library loaning you 50-60 titles can expect to have them returned between one and two months after collection, which is a big commitment on their part. And there are lots of other technical details that can expand your project timeline. The fragility of older titles means that there must always be someone monitoring the scanner to protect books from accidental damage. Ultimately, many of these older titles are works of art with huge cultural significance so, explains Iuliu, “if we can’t scan a book without damaging it, we won’t scan it.”

Further challenges arise after the title has been scanned. Some scientific, non-destructive titles have been written on old writing machines, so the ink quality can vary substantially from page to page. There is some technically intricate work needed to ‘clean up’ text, sharpen, or refocus letters – especially on the pages of these older titles – but what you get at the end is a publication much easier to read than the original. This attention to detail naturally takes time.

4. Be prepared to invest in the future

Not only does a digital archive project need substantial financial commitment to secure the safe transportation and scanning of thousands of titles, you also need to factor in the number of people needed to support an initiative of this scale. The DGBA involves over 40 people (across De Gruyter and Datagroup), working full-time for two years on this project alone.

Almost 40 people at Datagroup are dedicated to delivering the DGBA, with book scanning making up just one part of the overall process. After this comes the production of pre-print PDF files (a huge job requiring 18 full-time staff), then there’s the metadata capture, bibliographical maintenance and online production. Underpinning all this activity, and crucial to a timely and high-quality online archive, is the project lead.

De Gruyter has also dedicated five full-time staff to the project, with roles ranging from project management to bibliographic maintenance, book selection, transport and quality assurance. All of this comes with a hefty price tag, so committing to the development of a digital archive isn’t one that can be undertaken lightly. And cutting corners will only cost you more down the line.

5. Do sweat the small stuff

The goal of any digital archive initiative should be greater than ‘simply’ unearthing lost titles. To really effect change in the research community or make a greater cultural impact, these old or forgotten titles need to be made as discoverable and accessible as possible – through extensive metadata tagging (DOIs and MARC records). Scanning book content alone only paints half a picture. De Gruyter’s end goal is to make even the oldest and most obscure titles more available today, and a hundred years from now. It’s also aiming to make the digital archive as internationally relevant as possible by bringing back to life books in over 30 languages – all with translated bibliographic information – to better serve the global research community.

Scanning book content alone only paints half a picture. De Gruyter’s end goal is to make even the oldest and most obscure titles more available today, and a hundred years from now.

Speaking about the crucial role played by tagging archives with hundreds of thousands of pieces of metadata, Iuliu explains that the most problematic titles are the ones that have very little accompanying information. Without the correct or necessary bibliographic data, it’s impossible to make titles widely accessible to students and researchers through publisher or library websites and other book aggregators.

“If the bibliographic data for a title is missing, our team must meticulously locate and complete this information. We have specialist librarians carrying out this work, who not only need to be data specialists, but also fluent in multiple languages (including Latin), to be able to accurately translate bibliographic data.

Our in-house librarians check every individual title against several online catalogues and assign subject categories for indexing. This is often the bibliographic equivalent of finding a needle in a haystack, but no digital archive project can succeed without meticulous attention to the data.”

Is it worth the effort?

The most important effect of undertaking and investing in the lengthy, painstaking (and, yes, often frustrating) task of building a digital archive, is making important publications – many of which have been lost or forgotten – highly accessible via your website. Whether it’s helping a PhD student in Tokyo or a librarian in Oxford, you’ll be playing a pivotal role in narrowing the gap between readers and research-driven progress. Now, a university professor in Australia doesn’t have the near-impossible task of getting access to a rare title in Berlin – she searches your website and finds a pristine copy in seconds.

“All knowledge is out there. The important thing is making it as widely available as possible. For the first time, rare or forgotten titles are attracting global readerships and affecting real change in the 21st century – that’s surely worth effort. At least we think so!”

Danielo Methke, DGBA Project Lead, De Gruyter

[Title Image by [Kevin Grieve ], via Unsplash]