How “Second-Hand Libraries” Breathe New Life into Old Buildings

In the pursuit for sustainability, there’s no need to construct new buildings to create new libraries. From repurposed railway stations and supermarkets even to slaughterhouses, the potential to establish unique library spaces infused with character and community spirit is limitless.

This post is part of a series that provides think pieces and resources for academic librarians.

There is much talk in the library world about the role libraries can play in facing up to the challenges of sustainability and climate change through adopting green practices and ensuring that high quality information is available to all. New library buildings are designed to be energy efficient and environmentally sustainable, conferences on green libraries abound, and much thought goes into how we can run our libraries in the most sustainable way.

Most of us dutifully recycle paper and plastic, glass bottles, aerosol cans, and even building materials when embarking on a new library project. But what about the buildings that are already there? Do we reflect enough on the greater impact, both social and environmental, of recycling buildings themselves?

“There is a growing awareness of the need to preserve community identity, part and parcel of which is the need to retain historic buildings and the embodied energy they contain.”

A previous blog in this series looked at the role of libraries worldwide in supporting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 11 addresses the topic of sustainable cities and communities, aiming to create places that are inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. There is a growing awareness of the need to preserve community identity, part and parcel of which is the need to retain historic buildings and the embodied energy they contain; and not only energy but also individual and community memories, giving a sense of belonging so important to health and wellbeing.

Such places are often found in the heart of their community, whether it be on a high street in need of regeneration in the face of post-Covid remote working and online retailing, or in a much-loved building such as a church, a market house, or a library in a small rural town.

In their speech upon accepting the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize, the French architects Lacaton & Vassal noted that “Demolishing is a decision of easiness and short term. It is a waste of many things – a waste of energy, a waste of material, and a waste of history. Moreover, it has a very negative social impact”. Accordingly, the mantra in conservation circles is that the most sustainable building is the one that is already there. So, where do libraries fit into this compelling picture?

New Libraries in Old Buildings

Libraries, whether academic or public, generally lie at the heart of their communities, both physically and metaphorically. They are increasingly becoming one-stop shops for many services and community activities, with an enviable reputation for being knowledge driven and value-sensitive. At the centre of many cities, towns, and villages is a historic building in need of a new use, so it makes good sense to bring sustainably-focused libraries together with buildings in need of a new use.

All over the world, we can find examples of all kinds of old buildings which have been transformed into dramatic, welcoming, workable libraries with the inimitable wow factor. In an increasingly digital world, the experience of physical space is ever more important.

“In an increasingly digital world, the experience of physical space is ever more important.”

There is no doubting the beauty and historical fascination of many old buildings, nor the impact that being blighted by dereliction, vacancy, or lack of investment can have on the identity and perception of local residents. Rather than being seen as a liability, however, such buildings can offer an opportunity for communities to come together to devise new uses that will benefit them into the future. And what better use than a library, a place for both individual development and social engagement, which can serve as a community anchor and a haven for creativity and imagination.

That is not to say that reuse is without its challenges, particularly around IT infrastructure and environmental management. Low ceiling heights and solid walls can reduce flexibility, and the budget for restoration needs to be looked at in the context of the cost – social, economic and environmental – of demolition and disposal. Some buildings are more adaptable than others, but then again, those presenting the greatest challenges can often produce the most dramatic and effective results. In the hands of the right team, clients, and architects with imagination and a strong vision, almost any building can be transformed into a spectacular and practical new library.

Transformed Spaces Around the World

Large retail spaces and factories tend to be very flexible, but require skill and imagination to imbue them with character. A vacated Walmart store in McAllen Texas has become one of the biggest single-storey public libraries in the US. The open space of the supermarket was split into different sections, and a big box was transformed into a place with a sense of intimacy. The University of Luxembourg Learning Centre, on the other hand, occupies an early 20th-century building with lots of character, once used to store ore and coke. It is now a dramatic and functional library with a spacious and open interior punctuated by floating platforms.

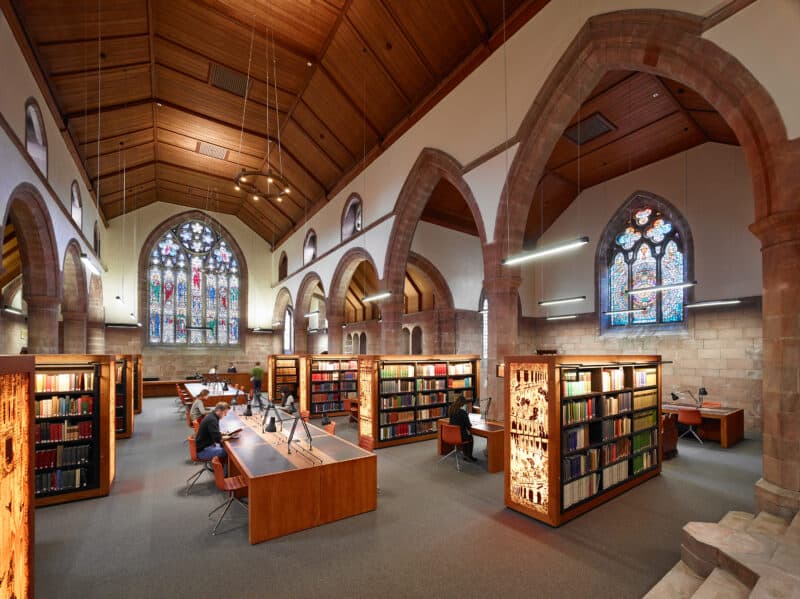

Declining congregations in some countries mean churches become redundant, and there are many examples of this building type being reused as libraries. In a chapel in Bogotá that is now used as an academic library, an almost free-standing structure was inserted into the historic shell of the building. Other examples for reused churches can be found in Ireland, Scotland, Netherlands, and Spain.

Railway stations and sheds have also been transformed into libraries, with perhaps the best known example being the multiple award-winning LocHal in Tilburg.

Adaptive reuse is increasingly seen as every bit as important and rewarding as designing a new building and makes up a major part of business in the construction industry. Examples of inspiring restoration projects abound.

In addition to the structures mentioned above, factories, industrial buildings, offices, hospitals, schools, cinemas, fire stations, courtyard houses, shops, barns, post offices, and many more have been transformed into libraries. Perhaps the most surprising examples of reuse include an abattoir and a cattle market. No doubt, readers of this blog can come up with many other projects, both straightforward and complex, and perhaps even bizarre.

Learn more in these related titles from De Gruyter

[Title image: Maison de la Littérature library in Quebec; photo by Tu Tram Pham via Unsplash]