How German Refugees Found a New Home in Ireland

Several hundred German-speaking refugees came to Ireland between 1933-1945. Their story has only recently been rediscovered - and we have a lot to learn from their experience.

Ireland has become a dream destination for German tourists since the 1950s, something for which Nobel Prize winning author Heinrich Böll’s Irish Journal, which was read by millions, is partly to blame.

But German and Austrian perceptions of Ireland in the 1930s were very different. It was seen as a poor and unstable country on the periphery of Europe, and people’s reactions, when told that Ireland was being considered as an exile destination, tended to be incredulous: “Are you crazy? People there have in their right coat pocket the liquor bottle, rosary beads in the left and in the hip pocket the revolver.”

While Ireland was not a preferred destination for refugees from Hitler’s Germany, it was certainly not particularly welcoming towards refugees. Having only gained independence in the early 1920s and battling with considerable economic problems – and indeed, emigration – Irish policy was mainly to keep anyone out who could become a burden.

The Irish Co-Ordinating Committee of Refugees

This only changed, at least to a small extent, in 1938, when the Irish Co-Ordinating Committee of Refugees was founded. Still, the number of refugees to be admitted initially was very small – ninety, to be precise. This was later increased with different monthly quotas and did not include refugees who came with the permission of the Department of Industry and Commerce or indeed illegally. Nevertheless, the overall number remained extremely small, about 400, which explains to some extent why the common narrative, that no Jewish refugee was let in, persisted for so long.

“Some remarkable people came to Ireland.”

But some remarkable people came to Ireland. Best known was Erwin Schrödinger, winner of the 1933 Nobel Prize in Physics, who was effectively headhunted by Irish Taoiseach (prime minister) Éamon de Valera and became the first director of the School of Theoretical Physics at the newly founded Dublin Institute of Advanced Studies.

Käte Lisowski was one of the few academic exiles who had previous personal and academic links with Ireland – she was a scholar of Celtic literature and had translated and published Irish folk songs and fairy tales collected and edited by, among others, Douglas Hyde who later became the Irish president.

Ernst Scheyer, a Jewish lawyer from Liegnitz who came with his family, later became a greatly beloved and influential lecturer of German at Trinity College Dublin. He also contributed with other Jewish refugees from Hitler’s Germany to the founding of an Irish Progressive Jewish Community that is still going strong today.

The wedding of Scheyer’s daughter Renate to Robert Weil from Berlin – who was taken in as an unaccompanied teenage refugee at the Quaker boarding school in Waterford – was the first wedding of the Progressive Jewish Community in Dublin.

The story of entrepreneurs is also instructive. They established or ran factories and provided employment in places on the periphery such as Castlebar, Galway, Longford and Carrick-on-Suir.

Altogether, some 400 people of varying religion, social status and political outlook came for shorter or longer periods, as visitors – or for good. Many of the refugees, especially the younger generation, integrated extremely well into Irish society, marrying here and living in Ireland for the rest of their lives

determined to make Ireland her home

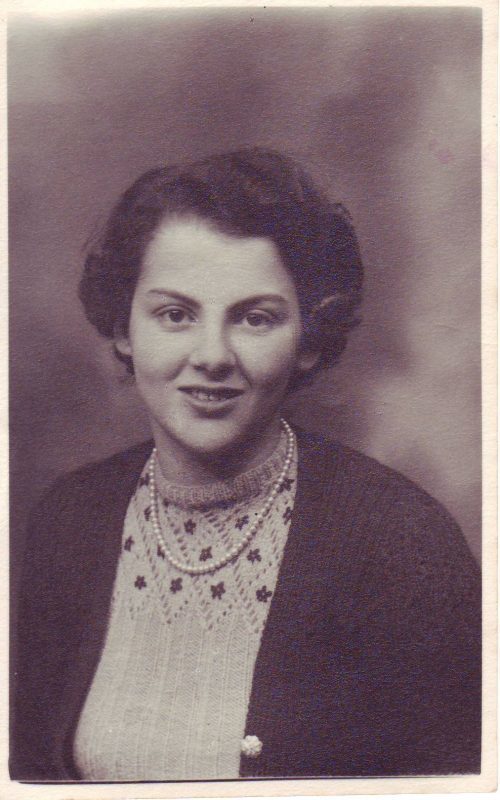

Thirteen-year-old Viennese teenager Lisa Fischer arrived with her sister Erika, three years older than herself, in early February 1939 in Ireland. Both were Protestant since their mother had converted prior to their birth. While originally the whole family had hoped to emigrate, chances opened up for the two daughters. Tragically, the parents later died in the Holocaust. At first Sweden seemed a possibility, then Ireland became an option under a scheme of the Irish Co-Ordinating Committee for Refugees to let a small number of children into Ireland.

Lisa was taken in as a border at St Margaret’s Hall in Dublin, then went to a school in Sligo and later she spent a lot of time in Gort with a family that took her under their wing and whose daughter became her closest friend.

Thanks to a scholarship, she started studying languages at Trinity College where she did well initially. But she left before taking her final exams, preferring to earn money for herself and to have more freedom, and took a position as a governess in Donegal. She married a local man in 1946.

“Tragically, Lisa died after giving birth to twin boys in July – just 22 years old. In her death notice, there was no indication at all of her refugee background.”

Tragically, she died after giving birth to twin boys in July – just 22 years old. In her death notice, there was no indication at all of her refugee background, she had become ‘Mrs. E. Lynn’, apparently entirely integrated in the host community – her personal background submerged.

The grieving husband left the twins with his sister-in-law who worked in the Cottage Home in Dun Laoghaire, which had been set up in the 1880s as the first children’s home in the United Kingdom to cater for children under six. When he got married again he took the boys back – but hardly ever talked about his first wife and they grew up without really knowing about her.

It was only by chance – in fact partially triggered by Brexit – that Lisa Fischer’s grandson in England initiated some family research into his grandmother which eventually led to the family learning much more about the Austrian background of their mother / grandmother.

Thanks to a research project at the University of Limerick focusing on exiles in Ireland and collecting anything to do with them, they also received letters she wrote to her best friend before her death, and her 1939 diary, which Lisa started in German, before switching to English straight away after arriving in Ireland, determined to make her new environment her home.

A German Linguist in Ireland

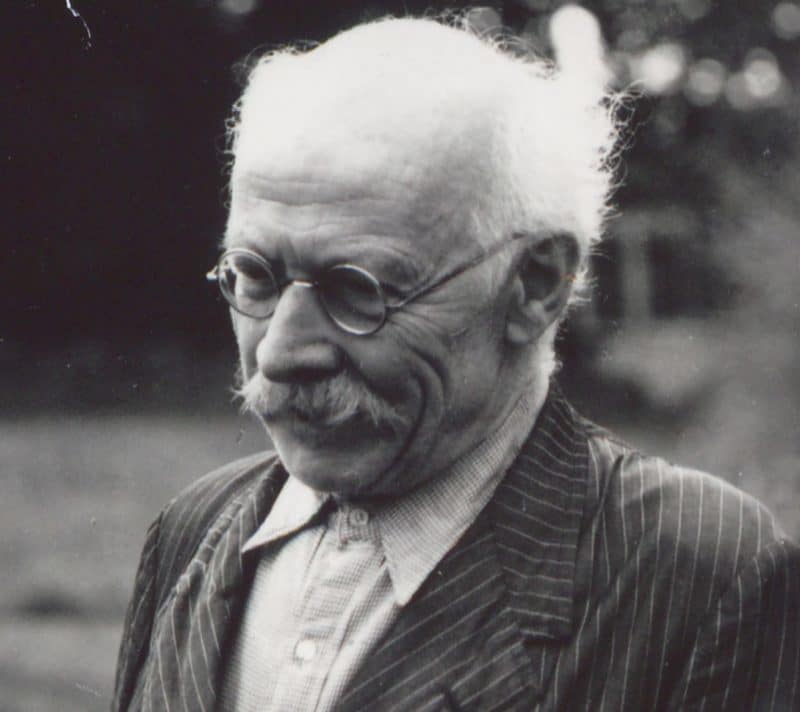

While not on quite so personal a level, there has also been increasing interest again in Ernst Lewy in the last few years.

Ernst Lewy was the first professor for Finno-Ugric languages in Berlin and first editor of the works of Jacob Michael Reinhold Lenz. He was also a teacher of Walter Benjamin at Berlin University.

“Walter Benjamin was so impressed by Lewy’s seminars about Wilhelm von Humboldt that he wanted to recruit Lewy as a contributor for his journal project Angelus Novus”

Benjamin was so impressed by Lewy’s seminars about Wilhelm von Humboldt that he wanted to recruit Lewy as a contributor for his journal project ‘Angelus Novus’. This, however, did not come to fruition. Lewy’s linguistic skills were considerable – he could speak German, French, Italian, Spanish, Russian, Swedish, Hungarian, Finnish, Mordvinic, Mari and Basque, and had a reading knowledge of Latin, Greek, English and Sanskrit.

His international contacts and the support of his Berlin colleagues meant that he was re-instated in Berlin in 1934 after having been suspended like almost all ‘Non-Aryan’ academics when Hitler came to power in April 1933. However, in January 1936 he was pensioned off. He had, like most other academics who came to Ireland, registered with the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning (SPSL) and was supported by it with funding supplied by British Egyptologist Alan Gardiner.

Furthermore, he was able to rely on networks established during his early Berlin years with students from Celtic Studies from Ireland. All together, this enabled him to emigrate to Ireland and concentrate on one major piece of research in 1937. This ‘opus magnum’, The Structure of European Languages was then published in 1942 in Dublin, by the Royal Irish Academy, in German!

His wife Hedwig and son Georg joined him in 1938; and in 1939, just before the war broke out, the family was complete with the arrival of their daughter Esther. During the war years, he lectured at University College Dublin where he taught very small groups of students in European Languages, Comparative Philology, Sanskrit, Old-Slavonic, and Finno-Ugric languages.

After the war, a return to his beloved Berlin University was not possible, partly due to Lewy’s age and state of health, and also to the new political situation in Berlin and at the university.

“He was a linguist who had emphasized long before Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf close links between language and culture.”

In 1947, he was appointed as one of only a handful of academics ever appointed as Professors to the Royal Irish Academy. He continued to engage in linguistic research and teach a small number of students, some of them even staying at his house outside Dublin where he lived until his death in September 1966, less than a week after he celebrated his eighty-fifth birthday.

He was a linguist who had, following his academic role models Wilhelm von Humboldt and Franz Nikolaus Finck, emphasized long before Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf close links between language and culture.

Lewy’s studies of Eastern Caucasian languages such as Awarian, his important role in the Department of Hungarian Studies at Berlin University and specifically his links to Finnish linguists have all recently attracted attention.

Albert Einstein’s first assistant

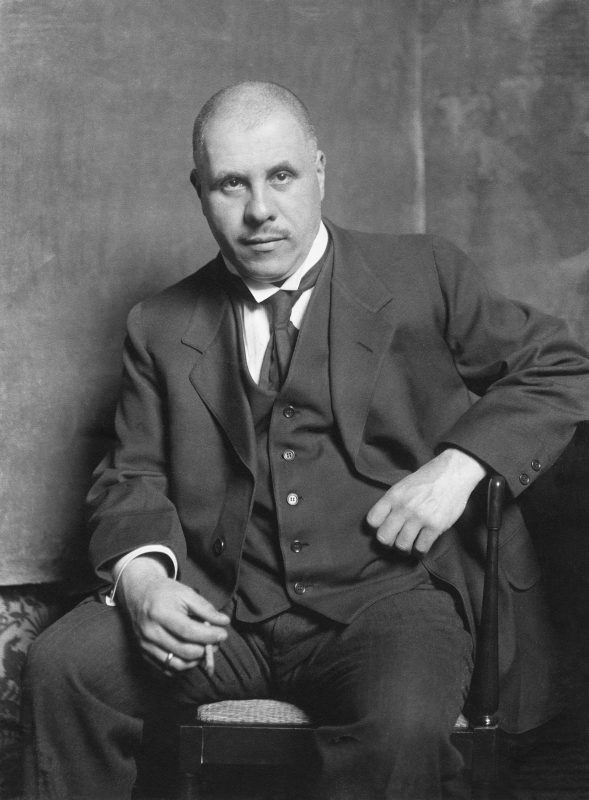

There has not been yet a major re-emergence of interest in Ludwig Hopf, but he is not forgotten either – and there is a very special connection to contemporary discussions on refugees as we will see. Born 1884 in Nuremberg into a family of well-established Jewish hop merchants, Ludwig Hopf had studied mathematics and physics at the best German universities at Berlin, Munich and in Zurich.

He did his PhD in the best possible place, in Munich under the tutelage of Arnold Sommerfeld who, together with Max Planck, Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr, is regarded as one of the founding fathers of modern theoretical physics and who was an unequaled teacher and supervisor (no one else had more students who went on to claim a Nobel Prize).

“Sommerfeld introduced Albert Einstein and Hopf, who got on well – both on a personal and a professional basis.”

It was Sommerfeld who introduced Albert Einstein and Hopf, who got on well – both on a personal and a professional basis.

Hopf joined Einstein in Zurich and went with him to Prague, he checked and corrected some of Einstein’s calculations, they published together – and later Hopf provided a thorough introduction to the theory of relativity in the popular series ‘Understandable Science’.

Hopf, a talented pianist, also accompanied Einstein playing his violin, and introduced him to C.G. Jung. While remaining in friendly contact with Einstein, Hopf then took up a position in Aachen which also offered the option for a habilitation, the second doctorate required in German academia and in 1923 he became professor for mathematics at the Technical University in Aachen.

However, following Hitler’s accession to power, he was suspended in 1933 and, despite strong support also among his colleagues, was pensioned off in 1934. His first priority then was to support the emigration of his children. Despite the support from Einstein and Sommerfeld, it took a long time to find a new academic home for himself.

Only in spring 1939, he, his wife and their youngest daughter as well as his parents-in-law were able to escape to England, the four sons having emigrated before them.

After a few months in England, he received an offer from Ireland, where an initiative from Trinity College allowed for the appointment of a “refugee of distinction”. In July 1939, he moved over with his family. He started lecturing in the autumn semester.

But shortly afterwards, in November 1939, he reported to his son Arnold, who was in Kenya, that he was not feeling too well – and a month later, Ludwig Hopf died, due to thyroid failure. In his eulogy at Hopf’s grave in Mount Jerome, Erwin Schrödinger summarised his life: “He was a friend of the great geniuses of his time, indeed he was one of them.”

Historical Lessons

And what about his link to refugee questions of today? For some years, there has been a small gathering at Mount Jerome Cemetery around the date of his death. He is remembered there with a short Christian prayer by Willie Walshe, an Irish priest who has worked in Kenya for many decades, and who buried Hopf’s son Arnold there.

A Jewish prayer is recited normally by Tomi Reichenthal, Holocaust survivor from Czechoslovakia who has lived in Ireland since the late 1950s. It was he who spoke out most poignantly in the context of the current refugee crisis, urging the Irish government to take up to 10,000 refugees.

“The reception of refugees in Ireland today is, apart from the increased official commitment, less welcoming than in the 1930s.”

This contrasted quite dramatically with the original commitment to take in only ninety Syrian refugees – a number reminiscent of the low number initially proposed in 1938. It was later quite considerably increased to 4,000 (though only a few hundred have come yet).

However, arguably the reception of refugees in Ireland today is, apart from the increased official commitment, less welcoming than in the 1930s when half a dozen aid organisations worked on behalf of the refugees, universities offered free places for students and invited researchers, work permits were given after a while in most cases – and many individuals opened their homes to refugees and were encouraged to do so.

Refugees today are housed in often crammed direct provision centres, not entitled to work and with few education prospects apart from school. Personal allowances amount to €19.10 per adult and €15.60 per child, recently increased from €9.60. The average length of stay in direct provision is more than four years. Maybe there are lessons to be learned – and in any case, there is a legacy of the refugees who came and the people who helped them that should be remembered.