From Persecution to Emancipation? The Pink Triangle and Queer History

How did the pink triangle, once imposed by the Nazis, get reclaimed by those it was meant to stigmatize? Has the triangle of sadness evolved into one of joy, of fear, of memory? This symbol of queer history contains multitudes.

During the fourth season of the highly popular reality TV show Ru Paul’s Drag Race UK, broadcasted by the BBC, the drag performer and now researcher at the University of Manchester Cheddar Gorgeous went down the runway of the 6th episode in a black and pink outfit reminiscent of AIDS activism and the SILENCE=DEATH design created by the AIDS coalition to unleash power (ACT UP) at the end of the 1980s. The poster, a big pink triangle facing upward on a black background, echoed the symbol forced upon men deported and persecuted for homosexuality during the Nazi regime.

Thousands of these queer men died in concentration camps, and their memory and rehabilitation was a long and fraught process that lasted until the 21st century. The conversation on these persecutions also goes beyond the criminalization of homosexuality, which is why historians are now discussing a larger context of oppression. The pink triangle used by the Nazis to brand queer men was pointing downward, and AIDS activists inversed the symbol in a gesture of hope, forcing people to talk about the epidemic, considering silence on the matter harmful and a form of genocide against the queer community.

Cheddar Gorgeous on Drag Race shining a spotlight on HIV activism with this iconic pink triangle runway look which paid homage to the ACT-UP movement. Cheddar also educated everyone watching that Undetectable = Untransmissable. pic.twitter.com/NBTNAS63b1

— ACT UP London (@ACTUP_LDN) March 1, 2023

The outfit worn by Cheddar Gorgeous is a call back to these thousands of activists across the Euro-American world who took the street wearing SILENCE=DEATH t-shirts and posters, shutting down government buildings and screaming as loud as they could in order to be heard and change the course of the epidemic. Other drag queens of the franchise later commented on Gorgeous’ outfit, telling the audience how Gorgeous was reminding younger members of the queer community “where we come from”.

It should be easy to sum this up right? A pink triangle pointing down is a symbol of oppression, and a pink triangle pointing up is a sign of emancipation. One is a symbol from the past, and the other a symbol of memory. If you forgive me being a cliché historian… it is a little bit more complicated.

Connecting Past, Present and Future

In the mid-1970s, a group of activists in the street of West Berlin were distributing flyers to passers-by, calling for an end to discrimination and a better commemoration of queer male victims of the Nazis. They were wearing pink triangles as badges. These men had contact across the Euro-American world. They corresponded, travelled, fell in love, or had sex with US Americans activists who also picked up the story of the men who had worn pink triangles. The symbol was already a symbol of emancipation, as it was used as a reversed stigma by activists in many countries before ACT UP updated the design on the SILENCE=DEATH poster.

Yet our analysis needs not to remain solely a diachronic investigation of the uses of the pink triangle. Pink triangles facing down were also synchronous to their penchant pointing up. For instance, in 1987 in the streets of the Bavarian capital of Munich, a man denouncing the new prophylactic measures of the regional government was holding a sign with a pink triangle pointing down with the sentence “Hey Bavaria! Have you forgotten this?” (Hey Bayern! Hast Du das vergessen?). He was walking in a demonstration headed by a banner with a pink triangle pointing up flanked by the motto SILENCE=DEATH (SCHWEIGEN=TOD).

“Queer injuries of the past are haunting the present, surviving as phantom pain, but can also inspire and anchor moments of resistance, joy, and endurance.”

As a symbol, the pink triangle, is a discursive two-way street, that is, it can be a representation of a discourse, but its various layers and significations can also affect their viewers according to context, space, and time. In other words, symbols carry many layers that accumulate over time and convey a multitude of narratives. Queer activists looking at pink triangle monuments commemorating Nazi persecutions can simultaneously think of AIDS activism and other historical emancipation movements that were inspired by and recuperated the Nazi stigma.

For example, the experiences and context of viewers looking at, let’s say, the monument at Nollendorfplatz in Berlin-Schöneberg, can eventually connect the plaque to various other moments of queer history, German or not. They can also hope for a better future devoid of queerphobia. Queer injuries of the past are therefore haunting the present, surviving as phantom pain, but can also inspire and anchor moments of resistance, joy, and endurance.

Recuperation and Reproduction

A visual conceptual history of the pink triangle cannot consequently be detached from a reflection on queer temporalities. Indeed, numerous key moments of the symbol’s journey are all simultaneously existing, appearing, and disappearing as vectors of memory and cultural belonging, depending on the viewer and the context in which the image is being viewed and used. This analysis of the pink triangle is intrinsically linked to negative emotions such as pain but also to the desire and need of using this pain as an impulse to fight back and celebrate queer joy. The recuperation of the triangle by the activists I’ve mentioned in West Berlin in the 1970s are intertwined with the use of the symbol as an icon of survival by other groups such ACT UP or even with the sale of pink triangle merchandise at the turn of the millennium.

“Cheddar Gorgeous was not only walking the runway of a reality TV show, but also walking on a bridge uniting moments of queer history.”

I have encountered a multitude of pink triangle memorabilia, ranging from keychains with pink triangles to gigantic pink triangle mascots during pride parades. Additionally, I have come across instances such as pink triangles incorporated into “I have voted” Democrat buttons and the symbolic used by Voices4, a direct-action group advocating for queer solidarity with chapters in London and Berlin. Writing this text, I find myself immersed in the archives, reflecting on an antifascist pink triangle button received at the Bishop’s Institute in London, resting on my desk. In all honesty, my office has by now transformed into a personal museum dedicated to the pink triangle.

Setting aside my personal kitsch and lack of work-life balance in my choice of décor, the symbol’s cohesion appears intrinsically connected to its widespread reproduction. The repetitive use of the motif undoubtedly underscores its significance and reinforces its importance through iteration. To put it differently, Cheddar Gorgeous was not only walking the runway of a reality TV show, but also walking on a bridge uniting moments of queer history.

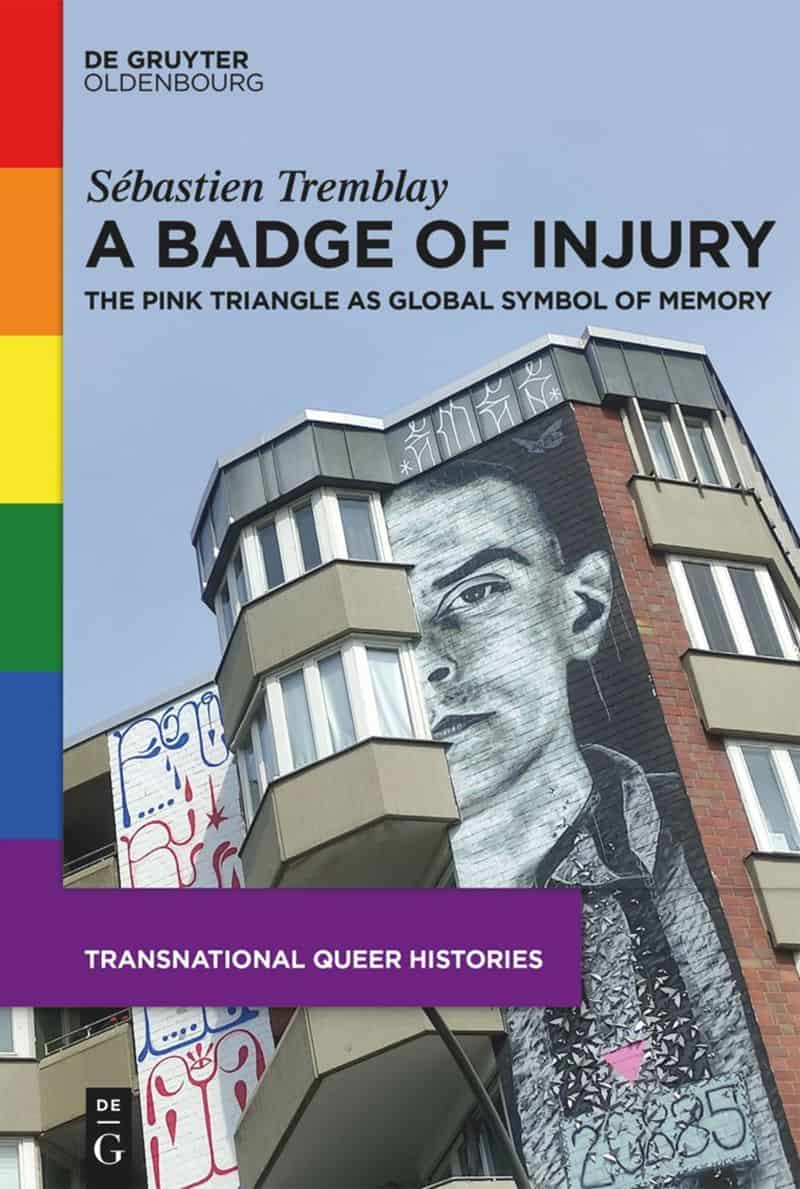

Learn more in this related title from De Gruyter

[Title image by Jove via Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0]