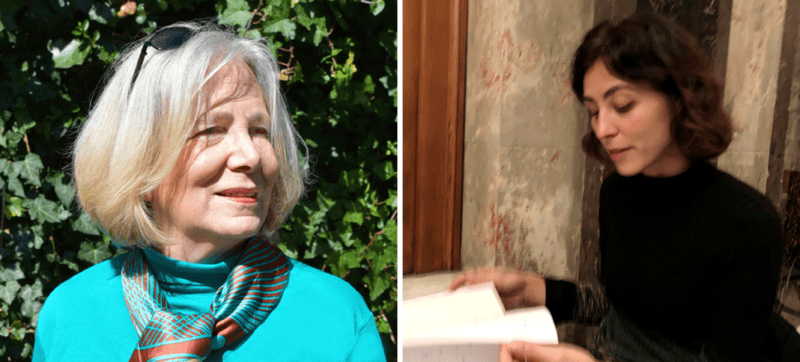

“Central European University Press Has a Unique Vantage Point”: An Interview With Frances Pinter and Emily Poznanski

This year, Central European University Press (CEUP), one of our publisher partners, is celebrating its 30th birthday. To honor this milestone, we talked to Frances Pinter and Emily Poznanski from CEUP about the past, present, and future of the press.

University presses offer high-quality academic publications, but also face particular challenges, including the struggle for financial sustainability and the need to ensure discoverability in the rapidly changing landscape of scholarly communications.

In 2019, we launched the De Gruyter University Press Library (UPL) with the mission to bring excellent scholarly content and ideas from university presses to a global audience. To achieve this goal, we digitize previously unavailable archive titles and provide online access to complete eBook collections from our partners. Countless unique and significant publications have found their way onto our platform over the past four years as a result of this initiative.

Currently, we are partnering with around 35 renowned presses from around the world – one of which is Central European University Press (CEUP). The press was founded in 1993 and the team have some exciting initiatives going on during their big anniversary year. To celebrate the occasion and our partnership, Alexandra Hinz from De Gruyter sat down with CEUP’s Executive Chair, Frances Pinter, and Director Emily Poznanski. Among other things, they talked about the press’s rich history, Open Access innovations in the book sector, support for Ukrainian publishers, and upcoming projects.

Alexandra Hinz: Central European University Press is celebrating its 30th birthday this year. Congrats! Frances, please tell us a little bit about the roots of the press and your involvement in it.

Frances Pinter: In 1991, George Soros set up the Central European University, which was meant to be a bridge for students from countries that were coming out of communism before going on to study in the West. He thought it needed a press, and he asked me to set it up. Back then I was a publisher in London, so I did it remotely. At some point I left the press but a couple of years ago I was invited to come back to look at it, modernize it and make sure that it was prepared for the digital world.

Originally the press was designed to fill the gaps in knowledge about Central and Eastern Europe and the former communist countries, with books written by people who were not necessarily all that well known in the West. Some of them have become globally known scholars since then, and the remit of the press broadened. It is now focusing on issues that concern the whole world, many of them having arisen from the legacies of the communist period and even earlier, as you’re seeing now with the war in Ukraine.

“The press aims to offer a pathway for a better understanding of Central and Eastern Europe.”

AH: Emily, you once said that “CEUP is a small press with a large mission.” Would you elaborate on that?

Emily Poznanski: The press aligns with the mission of the university, which is to promote open society and democracy through research primarily in the humanities and social sciences. That’s the big umbrella that we work under. Beyond that, the press, while based in Central Europe – out of Vienna and Budapest – has a unique vantage point. It aims to offer a pathway for a better understanding of Central and Eastern Europe, some would say the lesser-known part of Europe, and to pull out the themes from the region that are of global relevance.

FP: Sadly, so many of those issues are now of global importance, like the rise of autocracy, the limits on freedom, and how the war in Ukraine is affecting absolutely everything, everywhere. We’re right in the middle of it.

AH: What do you think are the advantages of being a “small press”?

EP: We move quickly – that’s an advantage. Quite a good example is when the war broke out in Ukraine, we were the first publisher to make our books freely available to everyone online. We did that within the first week, and then the industry followed.

“We give our authors a lot of special attention, particularly those for whom English is a second language.”

FP: Another advantage is that as a small company we do pay attention to every single book. We’re not a machine. We give our authors a lot of special attention, particularly those for whom English is a second language. So, our input into the books is probably greater than some of the very big multinationals. You can’t do that at scale.

AH: Both of you have already touched on the topic of the war in Ukraine. Frances, you recently launched the SUPRR (Supporting Ukrainian Publishing Resilience and Recovery) initiative – can you tell us more about its goals?

FP: The vision is for Ukrainian publishing to become as strong and healthy as possible. So, the mission of SUPRR is to help facilitate that. The goals that we’re setting ourselves is to build bridges between Ukrainian and Western publishers, mainly through the different trade associations. For example, ALPSP (Association of Learned and Professional Society Publishers) is offering free membership to Ukrainian publishers, and the AUP (Association of University Presses) offered free attendance to its annual conference. Now I’m working to get IPG (Independent Publishers Guild) on board. Through these connections and bridges, help to Ukrainian publishers can be extended at the grassroots level.

I have to thank the De Gruyter eBound Foundation because they’ve come through with the first grant, which is allowing us to hire somebody to help with the detailed work. We’re setting up various projects. Some of them are mentoring projects and internships, others help people make business contacts because they’re not able to travel, for example to get to book fairs. We are also planning workshops and webinars with a view to helping Ukrainian publishers prepare for the changes that will be required for European Union accession.

AH: Another initiative worth highlighting is CEUP’s open access model “Opening the Future,” which eliminates the need for book processing charges for selected publications. How does it work?

FP: It’s a collective action program, a “Subscribe to Open” membership type of program. In a nutshell, we offer libraries a package of 50 books from the backlist that are closed at a very reduced price. The money generated by this is put towards funding frontlist titles to go open. We began the program nearly three years ago and so far, we’ve raised enough funding to make 15 books open with another 35 going forward.

What’s really important about the model is that the libraries commit to three years, so we can plan ahead. We know how much money we will have, and the more libraries that join along the way, the more books we can make open access each year in the future. We offer perpetual access to those 50 books to any library that stays with us for three years.

“The more libraries join along the way, the more books we can make open access each year in the future.”

EP: There’s no inbuilt threshold in the model. So, you’re not staking everything on it; it adapts with the market. The more members we have, the more books we can publish in open access. If the interest drops, then we continue operations, which is a useful mechanism considering how much change there is going on around us. Also, it’s scalable. We have enough funding to fund 15 out of 30 books this year, but another press with a larger portfolio could scale the model. It’s a stretchy, adaptable one.

AH: Where do you see the future heading for open access books?

FP: Actually, I see it being bright. I worked with Niels Stern, who runs OAPEN, and Eelco Ferwerda, who used to run it. We wrote a landscape study, and our view is that there is enough money in the system because books are very small compared to journals in terms of budgets. We just need to convince the libraries to redirect their acquisitions budgets to open access so that it’s not just one of those experimental things that the scholarly communications division spends a little money on here and there. It has to become a regular thing because, particularly in HSS, there aren’t the kinds of pots of money sitting in research grants that there are for STM.

“Probably there will be more models on the book side, more variants that fit the different types of publications.”

EP: I think that the direction of travel is set and that not just by academia. It’s guided by what’s going on outside our industry and how we consume media. It’s mostly online, mostly free. We don’t pay for it directly, we just read as and when we want. So, the direction is clear, but how we organise this change, how long it takes and what unintended consequences we should look out for are another topic. The book landscape is more mixed than the journal landscape, which is further standardized. Probably there will be more models on the book side, more variants that fit the different types of publications. Will all books go open access? Probably not. Some don’t fit open access publishing. But I think for a large part of academic monographs that’s where it’s heading.

AH: Coming back to the press’s anniversary – I’ve heard about a few interesting new projects coming up this year, for instance “CEU Review of Books”. What is that about?

EP: The CEU Review of Books is going to be a separate site where we’re reviewing books about or coming out of the Central European region. What’s new about the site is that we’ll also be reviewing books published in local languages. So, for example, if there’s a very important book published in Polish for the Polish market, we’ll aim to review that in English. Again, in line with our mission, we want to offer a pathway to better understand Central European culture, history, politics, and its relevance in the world.

FP: The bulk will be short reviews of 1000 words each. In addition to that, there will be some podcasts and longer interviews.

AH: Then there’s also the new series “CEU Press Perspectives” – please tell us a little bit about that.

“The series invites authors to respond to the big questions of our time.”

EP: We’re launching our short book format with this series. The press has existed for 30 years, and the world has changed a few times over since then, so it’s an opportunity for us to rethink our place in it. The series invites authors to respond to the big questions of our time. What are the things we should be thinking about? What should we be asking in this moment of general uncertainty that we all feel – whether that’s economically, politically, or in other terms? It links nicely to the anniversary as it’s an opportunity for us to rethink the place of the press in the world today.

AH: Do either of you have any personal favorites in the CEUP portfolio?

FP: Actually, I cannot choose between all of my babies, it’s an impossible question for me. What I can say is that the first book we ever published won a Choice Outstanding Academic Book of the Year Award. It was “The Privatization Process in Central Europe” by Roman Frydman, Andrzej Rapaczynski and John S. Earle. What a way to start a publishing operation.

EP: I can mention a recent favorite of mine because I’ve been at the press for a shorter time, so it’s easier for me. We published a beautifully illustrated print atlas by Tomasz Kamusella, which goes through the history of languages in Central Europe: “Words in Space and Time.” We published the eBook in open access. It’s a gorgeous publication, and the online version was downloaded 15,000 times on the MUSE platform alone in the first few months, all over the world. It’s just a perfect example of how to combine print and digital.

AH: For the final question, I would like to talk about our partnership. Emily, what motivated CEUP’s decision to collaborate with De Gruyter, and would you consider this cooperation a success thus far?

“Coming on board with the University Press Library program was one way of achieving sales representation, especially in the US.”

EP: Being a small press comes with a long list of challenges and one of them is that we don’t have a direct sales force. Coming on board with the University Press Library program was one way of achieving sales representation, especially in the US. That was the main reason for joining the program, and it has been an absolute success for us. The revenues in the first year were significant for the press.

FP: I would like to add that I really value the fact that the people at De Gruyter we work with are great in sharing information and ideas. They just help us with thinking through things because they have other information on tap that we don’t.

AH: That’s great to hear, thank you for these nice closing words and thank you for this interview, Frances and Emily!

[Title image by Daniel Vegel]