P.S. There is no Bible 1.0

As no one would probably argue against the fact that the copyists and editors of these holy texts were themselves very much human, how can we be so sure they picked the “right” ones? Perhaps we are missing out on some important thoughts?

Should we then just ignore the ones that were not deemed worthy of inclusion in the different types of canons?

To get a fuller picture of ancient Judea, its history and its wisdom, you have to actually read the apocrypha and pseudepigraphs, which researchers have compiled and published with annotations.

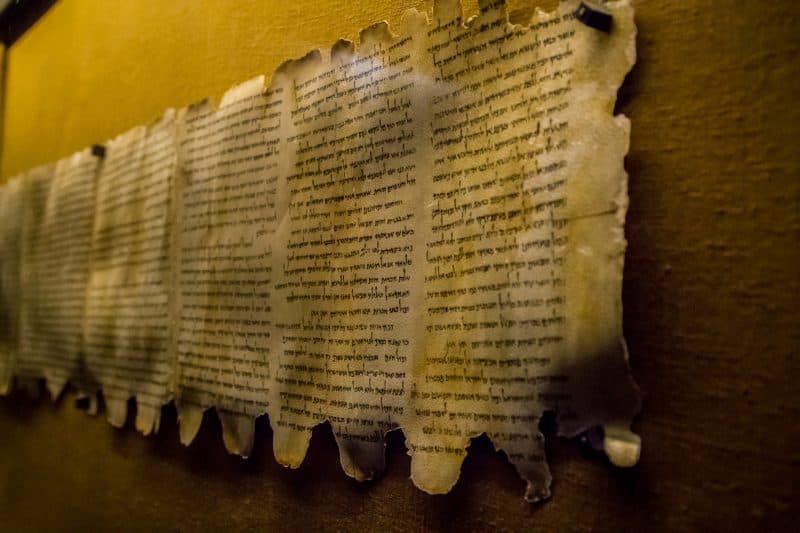

This is especially important after the 20th century findings of new Hebrew (and partly Aramaic) source material in the form of the Dead Sea Scrolls from the Qumran Caves and the Coptic gnostic texts at Nag Hammadi in Egypt. The hundreds of – mostly fragmentary – scrolls discovered in the 1940s to 1950s in the caves nearby Qumran contained parts of known as well as hitherto unknown texts. According to Professor Lichtenberger, some evidence points to the conclusion that they originally stemmed from the Temple Library in Jerusalem and were hidden away in the caves to protect them from the Roman conquerors in the first century BC. Wherever they ultimately came from, they certainly provide important new insights for scholarly research.

When diving into the world of early Jewish writings, readers will discover a wide array of different types of text. Instead of keeping up the somewhat artificial distinction between apocrypha and pseudepigraphs, it makes more sense to group the texts together according to their content rather then their authorship: Historical and legendary tales, instructive and didactic texts, poetic writings and number of apocalyptic texts.

As Professor Lichtenberger points out, many of the writings are meant to provide additional information to the already well-known Biblical stories. Almost a bit like the much-maligned “fanfiction” of today. The authors of these texts expect that the readers are familiar with the original stories and try to attach themselves to certain writers or genres. Often, they try to fill in narrative gaps. An example of this is a text dwelling on the beauty of Sarah, the wife of Abraham, a figure well known from the Book of Genesis. There, she is repeatedly described as exceptionally beautiful, without any more details. The corresponding text tries to define the exact way in which she is beautiful, perhaps so that readers will have a better understanding as to why the Pharaoh covets her.

Some of them are stories widely known today, such as the Book of Judith, telling the story of the beautiful and fierce widow Judith who seduces and then beheads the enemy general Holofernes. As the motif of Holofernes’ beheading has inspired artists for centuries, many visitors to art galleries may not realize that the tale inspiring these paintings is not considered a canonical part of the Bible, at least not by Protestants. The same goes for another story which became a hit with painters for centuries: the part of the Book of Daniel telling the story about the beautiful Susanna having to fend off two lecherous elders. In court, of course no one believes her version of the story and Daniel has to come in and save the day. Apparently, stories about the self-empowerment of beautiful young women were not considered first-rate material for inclusion in the Biblical canon by all its editors. Thus, in order to gain a fuller picture, the apocrypha provide invaluable insights.

Speaking of the role of women in Biblical texts, there is an apocryphal story in the 3rd Book of Ezra stressing the importance women have in the lives of men. In it, there is a contest between three young men, bodyguards to King Darius. They all state before their King what they consider the strongest thing they know and he must decide who of them is the wisest. The first man says it is wine, because it can lead the mind of anyone drinking it astray, the second says it must be the king on whose command men go out and fight. The third one then says it is the women who are strongest (a later revision adds “truth” to the mix). The beautiful passage reads: “Gentlemen, is not the king great, and are not men many, and is not wine strong? Who is it, then, that rules them, or has the mastery over them? Is it not women? Women gave birth to the king and to every people that rules over sea and land. From women they came (…) A man leaves his own father, who brought him up, and his own country, and clings to his wife. With his wife he ends his days, with no thought of his father or his mother or his country. Therefore you must realize that women rule over you!”. After that, it is no surprise the third guy wins the contest.

As mentioned before, there also is a whole group of apocalyptical writings. When talking about “the” apocalypse today, we usually refer to the Apocalypse of John (also known as the Book of Revelation), the last book of the New Testament, since it has become such an integral part of Christian eschatology. But since the centuries before Christ were already overshadowed with a pervasive and wide-spread doomsday mood, there was no shortage in apocalyptic writings. Some of them, like the 4th Book of Ezra, try to grapple with the idea of theodicy. After witnessing the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD, the pseudonymous author of the text is trying to understand how a righteous God could let this happen. Others, like the Greek Apocalypse of Baruch (also known as 3 Baruch), the Greek Apocalypse of Ezra and the Apocalypse of Zephaniah provide glimpses into the celestial realm and the netherworld.

It is impossible to mention all of the early Jewish writings and their content here, since there are dozens of texts of varying lengths and literary quality. Of these, only a small group is included in the apocryphal section of some Bible editions, so that most of these texts aren’t known outside of scholarly circles.

Still, all in all this little selection goes to show that archaic religious writings tend to be far from straightforward, at least as far as the Old Testament is concerned.

As the world seems to get more complicated every year and we start longing for a primeval truth, we still need to keep in mind that it was by no means a simple place when the writings now revered as the Holy Bible were compiled. Many different people were involved in the process. At first, there were the authors writing the texts, followed by a long period in which a larger group of people came to accept the texts. Finally, there were those who chose which texts to include in the canon.

So if you are looking for fundamental truths in the Bible, you should at least consider having a look at the writings that ancient Judeans intended as a contribution to it.

This is the second installment on Jewish Writings from Roman-Hellenistic Times series from our publishing partner, Gütersloher Verlagshaus. Read the first part here!

[Title Image by salajean on Getty Images ]