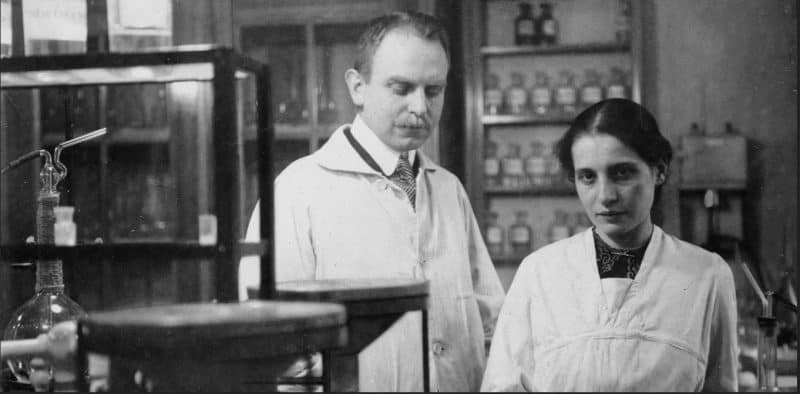

Lise Meitner: “A physicist who never lost her humanity”

Against all odds, Austrian-born Lise Meitner devoted her life to a career in nuclear physics. Today we look back on the achievements of a brilliant woman who many believe was once robbed of the Nobel Prize.

This article is an excerpt from the book “Women in European Academies: From Patronae Scientiarum to Path-Breakers”; the chapter on Lise Meitner, including full references can be found here.

“It brings me great pleasure that with the election of your person in particular, esteemed Professor, the first woman has been elected to the ranks of the Academy’s membership since its founding.” The president of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW), Heinrich Ficker, wrote these words of congratulation in a letter dated 9 June 1948 to Lise Meitner, a physicist already famous beyond Austria’s borders, on her election to Corresponding Member Abroad for the Division of Mathematics and the Natural Sciences.

Lise Meitner was indeed the first female member of the Academy, which had been founded in 1847. As a woman and a Jew she was elected into an academy whose membership only three years prior had consisted of many members of the National Socialist party (NSDAP) (approximately 50%) and which had not significantly changed its composition since the NSDAP had been outlawed in 1945. In 1949, the same honour of being elected the first female member was conferred on her at the German Academy of Sciences in Berlin. A few years previously she had been elected to the Academies in Stockholm, Gothenburg, Copenhagen and Oslo. In 1955, she was named an External Member of the Royal Society, an honour that meant a great deal to her, and in 1960 this was followed by her election to membership of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The grounds for Meitner’s election to the ÖAW were her fundamental research in the field of nuclear physics and her contribution to the study of nuclear fission. While in exile in Sweden over the New Year 1938/39, she had succeeded in explaining the physics behind the puzzling results of an experiment performed by her former Berlin colleagues Otto Hahn and Fritz Straßmann. When uranium was irradiated with neutrons, the radiochemical analysis revealed traces of the element barium. This indicated that the uranium atom had ‘split’ into lighter fragments, a result which the two chemists were unable to explain. Lise Meitner, together with her nephew Otto Robert Frisch, interpreted the reaction as nuclear fission and calculated the huge quantity of energy released in the process. Nevertheless, in 1946 Otto Hahn was the sole recipient of the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for his discovery of the fission of heavy nuclei”.

That Lise Meitner’s involvement in this epoch-making scientific breakthrough was crucial, and yet recognition for it went instead to Hahn, can be considered a prime example of the lack of acknowledgement and visibility granted to women in science. It is particularly striking because Lise Meitner was nominated for the Nobel Prize a total of 48 times by colleagues – without success. That she went empty-handed in 1946 has been cited by the science historian Margaret W. Rossiter as paradigmatic of the unequal distribution of fame between women and their male colleagues. At one point Rossiter considered naming this phenomenon the ‘Lise Effect’, but instead decided on the ‘Matilda Effect’ – now the conventional term in the history of science – after Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826–1898), an American feminist and early sociologist of knowledge.

A Difficult Path in Science

In her short biographical essay Looking Back, published in 1964, Lise Meitner summarised that her life had “not always been easy” but that it had been full thanks to the “wonderful development of physics during my lifetime and the great and lovable personalities with whom my work in physics brought me in contact”.

She did not have an easy start to her scientific career. When, at the age of 13, she realised that she wanted to study mathematics and physics, women were still officially barred from studying at a university in many parts of Europe. In Austria, women were permitted to take the grammar school (Gymnasium) leaving certificate (Matura) as external students from 1878 onwards, yet this did not entitle them to study at an Austrian university.

“Looking back, Meitner described the time before going to university as lost years.”

Lise Meitner was born in Vienna on 7 November 1878 as the third of eight children to Philipp Meitner, a Jewish lawyer, and his wife Hedwig. Her parents were keen to enable not only their sons but also their five daughters to study. For this reason, after leaving secondary school Meitner trained as a French teacher from 1893 to 1895. She could only embark upon her actual goal – exploring her scientific interests through study at a university – after women were admitted as regular students (to philosophical faculties from the 1897/98 academic year, and to medical faculties from 1900/01).

Starting in 1898, Meitner was coached privately for the school leaving certificate by Arthur Szarvassi, a young assistant at the Institute of Physics at the University of Vienna. In 1901 she, Henriette Boltzmann, the oldest daughter of Ludwig Boltzmann, and two other young women took and passed the school leaving certificate at Vienna’s Akademisches Gymnasium. At the age of 23 she could now finally pursue her studies in mathematics and physics. Looking back, Meitner described this time before going to university as lost years.

The biggest influence on Meitner during her studies was Ludwig Boltzmann. In his lectures on theoretical physics, he passed on his enthusiasm for questions of the atomic structure of matter to a whole generation of physics students in Vienna. Meitner later remembered his lively lectures with pleasure, as well as the musical evenings to which he invited his advanced students, male and female.

Her doctoral thesis on Thermal Conductivity in Non-Homogeneous Bodies was supervised by Franz Exner, some of whose pupils went on to become prominent physicists, for example Egon von Schweidler, Stefan Meyer, Karl Przibram, Victor Franz Hess, Erwin Schrödinger and others. On 1 February 1906 Meitner became the second woman to be awarded a doctorate in physics from the University of Vienna. That her scientific achievements and competence were immediately recognised and respected can be seen from the publication of her thesis and a first independent work, Some Conclusions Derived from the Fresnel Reflection Formula, in the Proceedings of the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Vienna in 1906.

Having taken the teaching diploma in mathematics and physics, the decisive push for Meitner to focus on scientific work came from Stefan Meyer, who later became the director of the Institute for Radium Research, founded in 1910 at the Imperial Academy of Sciences. After Boltzmann’s death, Meyer temporarily ran the university’s Physical Institute and he enabled Meitner to take part in experimental research on determining methods for measuring radioactive substances.

Alongside Paris, Cambridge and Berlin, Vienna was a centre for research in the new field of radioactivity. The capital of the Habsburg Empire enjoyed an advantageous position in the field due to its exclusive access to the residue of the mineral pitchblende from the uranium mine in St. Joachimsthal (Jáchymov) in Bohemia. This material formed the starting point for the production of radium and its radioactive by-products. At that time, it could not be acquired in sizeable quantities from anywhere else. Through an agreement with the Ministry of Agriculture, the Imperial Academy of Sciences had managed to secure access to ten tonnes of pitchblende residue. This allowed it to obtain four grams of radium chloride in 1904/05, at that time the largest quantity of radium in solution worldwide.

To coordinate the use of this valuable material in radioactivity research, in 1901 the Academy set up a Commission for the Research of Radioactive Substances. In 1907 the head of this commission, Franz Exner, reported in the Academy’s Almanach on the successful experiments carried out on radium and its by-products polonium and actinium by his former students Stefan Meyer, Egon von Schweidler and ‘Dr L. Meitner’. Meitner’s study On the Absorption of Alpha and Beta Rays, which Meyer encouraged her to pursue, not only gained attention in Academy circles but was also published in 1906 in the journal Physikalische Zeitschrift – already her third publication.

On the basis of these scientific successes, which Meitner achieved through her work at the University’s 2nd Physical Institute and in collaboration with the Academy’s Radium Commission, in 1906 the inventor and industrialist Carl Auer von Welsbach offered her a well-paid position at his gas lamp factory. Meitner declined, since the industrial production of radioactive preparations did not interest her as much as scientific work on what were primarily theoretical questions. However, her prospects for gaining employment at the 2nd Physical Institute in Vienna were poor, not least because of competition between Exner’s young and ambitious former pupils. An application for a research job at Marie Curie’s laboratory also came to nothing. When, in 1907, Meitner heard a lecture given by Max Planck she abruptly decided to go to Berlin for a few semesters in order to gain “some real understanding of physics” from Planck. An unhappy relationship, which is vaguely alluded to in the literature, may also have been a contributing factor in her decision to leave Vienna.

Career in Berlin

In her memoirs, Meitner admitted that when she set off for Berlin in September 1907, she knew “nothing at all about German universities”. At that time women could not study for a degree at a Prussian university but only audit lectures, and then only with the express permission of the lecturer, which Planck did grant to Meitner. Very quickly she became part of his circle of students and he also invited her to his home. In order to be able to continue experimental research, she approached the dean of the Institute for Experimental Physics, Heinrich Rubens, who offered her a place in his laboratory. In addition, he introduced her to the young chemist Otto Hahn, who at that time was looking for a physicist to collaborate with on his radioactivity research. Hahn invited Meitner to work in his laboratory. Meitner gladly accepted the offer, since she expected to work on an equal footing with the affable radiochemist of her own age. This did indeed mark the beginning of over 30 years of fruitful collaboration, and a lifelong friendship.

“As a woman, she had to enter and leave the institute by the back door.”

Otto Hahn, four months younger than Meitner, had gained his doctorate in chemistry from Marburg in 1901, just as Meitner was finally allowed to embark on her university studies. In 1904 he went to London to further his knowledge in the emerging field of radiochemistry with William Ramsay, then to Montreal in 1905 to work with Ernest Rutherford. Having discovered ‘radiothorium’ in 1904 and two further radioactive substances, Hahn was already well established as a scientist when, in summer 1906, he was taken on as an assistant by Emil Fischer at the 1st Chemical Institute at the University of Berlin. He had even set up his own, simple laboratory in a former carpenter’s workshop. Fischer granted Lise Meitner permission to work with Hahn for no salary but as a woman, she had to enter and leave the institute by the back door. This restrictive rule was only lifted with the general admission of women to study at Prussian universities in the winter semester of 1908/09.

What started out as two hours a day of joint work quickly grew into intensive research. The “intuitive talent” of the chemist Hahn and the “analytical, critical intellect” of the physicist Meitner complemented one another. The scientific milieu at the Physical Institute with its ‘Wednesday Colloquium’ was also stimulating. Organised by Heinrich Rubens and later Max von Laue, these meetings brought together a small group around Max Planck, Walther Nernst and, from 1913, Albert Einstein, as well as Otto von Baeyer, James Franck, Gustav Hertz and others. The first success of Hahn and Meitner’s collaboration came in 1908 with the isolation of a new radioactive substance, actinium C. And with Hahn’s discovery of radioactive recoil in 1909, they now had at their disposal a method for separating different radioactive substances from one another and of determining new decay products.

In their joint field of work, researching the energy spectra of beta radiation, Hahn and Meitner, together with Otto von Baeyer, developed the first magnetic beta spectrometer at the Physical Institute. By 1915 they had used this to investigate the beta spectrum of nearly all radioelements.

Financial support from her parents allowed Meitner to gain scientific experience in an unpaid position. In 1912, following five years of successful research in the carpenter’s workshop, Meitner gained her first paid position when she was appointed assistant to Max Planck. This made her the first woman to be a salaried member of academic staff at a Prussian university. That same year, Otto Hahn became a member of the newly-founded Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (KWI) of Chemistry and was tasked with running a small department for radiochemistry. In 1913 Hahn and Meitner relocated their laboratory from the carpenter’s workshop to a new building in Berlin-Dahlem. Meitner was also elected to the institute, initially as a guest member, and the department for radioactivity was now designated the ‘Hahn-Meitner Laboratory’. In 1914 Meitner declined an offer from her former teacher, Anton Lampa, to move to the University of Prague to work on her project for the university teaching qualification (Habilitation) with the prospect of a professorship.

The outbreak of the First World War interrupted Meitner’s and Hahn’s joint work, the focus of which had now shifted to the search for the mother substance of actinium. While Otto Hahn agreed to be assigned to the gas warfare department run by Fritz Haber, his colleague at the KWI of Chemistry, Lise Meitner trained in radiography and took a nursing course. From 1915 to 1916 she worked as a radiography nurse in hospitals for wounded soldiers, mainly in Lemberg/Lviv and Trient/Trento. Having returned to Berlin, in 1917 she was tasked with establishing and running her own department of radioactive physics at the KWI of Chemistry.

Collaborations with Vienna

Meitner’s contacts with the Institute for Radium Research, which had been established at the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Vienna in 1910, were vital to what she and Hahn achieved at the KWI. In the period around 1910, the Academy in Vienna, as the representative of scientific institutions in the German speaking parts of Austria, was in possession of around half of all the radium used in scientific research. In particular Stefan Meyer, with whom Meitner was on friendly terms, had managed to build up good contacts with the radium industry since 1905. Although he was also Meitner’s scientific competitor, he supported his colleague in Berlin by procuring this indispensable research material for her.

From 1917 onwards, Meyer sourced the necessary radioactive materials, managed to get an export permit from the ministry responsible in spite of an export ban, and sent Meitner preparations from his own private collection. One immediate result of this support was the isolation of the radioactive decay product protactinium in 1918, the sought-after mother substance of actinium. Meitner carried out the necessary experiments largely on her own because Hahn’s war work allowed him only occasional visits to Dahlem. Yet the publication of this finding appeared in 1918 in the journal Physikalische Zeitschrift under both names – with Hahn the first-listed author.

In the 1920s, research at the KWI focused primarily on beta and gamma radiation and made significant contributions to understanding the structure of the nucleus, the atomic shell and the radioactive decay processes. Again Meitner used her good contacts with Vienna to request a loan of actinium in 1923, on the basis of which she was able to continue her experiments into the beta and gamma radiation of uranium.

In recognition of her achievements, in 1919 she was awarded the title of ‘Professor’ by the Prussian Ministry of Science, Art and Education at the urging of Emil Fischer, Max Planck and Walther Nernst. In 1922 she became the first female physicist in Germany to receive the university postdoctoral teaching qualification (Habilitation) from the University of Berlin for her study On Beta Line Spectra and their Relationship to Gamma Radiation. In 1926 she was appointed a non-tenured associate professor (nichtbeamtete außerordentliche Professorin) for nuclear physics, thus gaining professional parity with her colleague Otto Hahn. Previously, in 1924, she and Otto Hahn had been nominated for the first time for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

For her work on researching the beta spectrum, Meitner was awarded the Silver Leibniz Medal of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in 1924, and in 1925 she was the first woman to receive the Ignaz Lieben Prize of the Academy of Sciences in Vienna “for her treatises on the beta and gamma rays of radioactive substances published between 1922 and 1924 in the Zeitschrift für Physik”. The nomination emphasised her pioneering achievements: in 1921 she had “carried out the first attempt to gain ideas about the constitution of the inside of the nucleus of radioactive substances, which allowed the deduction of the manner and sequence of the substances of a decay chain” (quote from the minutes of the committee meeting regarding the award of the Lieben Prize in physics 1925).

“Awards and honours did not go hand in hand with equality in professional academic life.”

She was also held in high esteem internationally and her work was regarded as equal to that of her male colleagues. In addition to these honours she was elected a member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina in 1925 and a corresponding member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences in 1926. Yet this did not go hand in hand with equality in professional academic life. When Victor Hess was appointed to the chair in physics in Graz in 1936, it emerged that during the preliminary stages of selection, Meitner had also been in contention as a candidate alongside Fritz Kohlrausch. However, “an overwhelming majority of the faculty […] felt that the present task required a man. That is the only reason why the name Lise Meitner did not appear among the recommendations, although it is in no way inferior to the other two in terms of a justified international reputation.”

Racist Discrimination, Emigration and Nuclear Fission

For the internationally networked, stimulating atmosphere of Berlin’s physics community and that of the KWI in Dahlem, where Meitner lived in a spacious apartment in the Direktorenvilla, the National Socialists’ seizure of power represented a radical rupture. When the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service came into force, Meitner’s authorisation to teach was withdrawn on 7 April 1933 due to her Jewish background. As an Austrian citizen, she was able to continue her work at the KWI, which was mainly non-state financed, and she remained in Berlin for as long as this was possible.

Inspired by Enrico Fermi’s experiments, from 1934 on she, Otto Hahn and Fritz Straßmann experimented on the production of what were known as transuranic elements, which it was thought could be formed by irradiating uranium with neutrons. Her only book, The Structure of the Atomic Nucleus, also appeared during this period. It was written together with her assistant, the future Nobel Prize winner Max Delbrück. With the loss of her teaching permission and the right to give public lectures, Hahn now presented their joint scientific findings in public. Lise Meitner’s fame, reputation and scope for action were henceforth diminished not only because of the structural inequality between men and women in the sciences, but also because of racist discrimination and later persecution under the National Socialist dictatorship. Looking back in 1947, she regretted not having left Germany immediately like Albert Einstein or James Franck, not only for practical but also for moral reasons.

It was only after the ‘Anschluss’ (‘annexation’) of Austria, which meant the loss of her Austrian citizenship and therefore the validity of her passport, that Meitner became conscious of her desperate situation. With the help of a friendly Dutch colleague, Dirk Coster, she was able to flee on 13 July 1938 to the Netherlands, where she arrived with two small suitcases, ten marks and a ring given to her by Otto Hahn for any eventuality. Three days previously she had posted off her final joint paper on the search for transuranic elements to the journal Naturwissenschaften. While staying with Niels and Margarete Bohr in Copenhagen in August 1938 she received an invitation from Manne Siegbahn to work at the Nobel Institute in Stockholm, and an entry permit for Sweden.

Having arrived in Swedish exile, Meitner was disappointed to discover that the equipment at the Institute did not meet the demands of her research field and that, without staff or apparatus, she could only continue her experiments under difficult conditions. Her linguistic and attendant social isolation – she quickly learnt to understand Swedish but found speaking the language difficult – was swiftly followed by scientific isolation.

Her correspondence with Otto Hahn was therefore all the more welcome. This began in December 1938 and has gone down in scientific history. Hahn and Straßmann were continuing to experiment in Berlin without Meitner in an attempt to prove Enrico Fermi’s theory of transuranic elements. In his letter, Hahn asked Meitner for an explanation of the unexpected results of the neutron irradiation of uranium. He and Straßmann recognised that the uranium had ‘split’ into lighter fragments, which they identified as barium. But was this possible? “In case you can suggest anything that could be published, then it would still be a study by the three of us”, Hahn wrote to her in his appeal for an explanation.

In the first days of 1939, while spending the Christmas holidays with her nephew, the physicist Otto Robert Frisch, with friends in Kungälv in southwest Sweden, Lise Meitner actually succeeded in explaining the reaction theoretically as nuclear fission and calculating the huge amount of energy that this would release. Meitner and Frisch took their time and published their article in the journal Nature in February 1939. Later, the fact that they did not publish their findings immediately would play a role in the matter of the award of the Nobel Prize: in some evaluations of her nomination, the credit for having produced the theoretical explanation for nuclear fission would go instead to Niels Bohr.

In 1947 Meitner transferred to the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm in order to run the nuclear physics department at the Physical Institute. She declined an offer from Fritz Straßmann to accept a professorship in physics at the University of Mainz because of concerns and doubts about the mentality and confidence of younger colleagues. In 1948, when she was sure that she could retain her Austrian citizenship, she took Swedish citizenship. She ran the nuclear physics department until the early 1950s, only stepping back when the Max Planck Society granted her claim to an old-age pension at the age of 75. In 1960 she moved to Cambridge to be near her nephew Frisch. She died there on 27 October 1968, a few months after Otto Hahn and shortly before her 90th birthday.

Honours, Commemoration, Legacy

Lise Meitner’s scientific achievements garnered international recognition early on, as shown by her numerous nominations for the Nobel Prize from 1924 onwards. She became more widely famous when, six years after the discovery of nuclear fission, the two US atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, turning her worst fears into reality. Meitner had refused an invitation to work on developing the atom bomb and, until the last, she had hoped that this would prove impossible. In spite of this, journalists labelled her the ‘Mother of the Atom Bomb’. In 1946, during a stay as a visiting professor at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., she was voted ‘Woman of the Year’ by the Women’s National Press Club for her contribution to bringing the war to an end – reasoning that is difficult for us to follow today. President Truman was also present at the award ceremony.

She also came to public attention in Austria in this context. An article written by her on ‘The Atom’, in which she reported on the experiments carried out with Hahn and Straßmann, was printed in the Wiener Kurier newspaper in early 1946. In 1953 she gave a talk at the Wiener Konzerthaus concert hall on ‘The Atom and the Universe’ and on future, peaceful uses for nuclear energy. The lecture clearly resonated with a broader public and was reported on in several newspapers. That she was described in these reports as Otto Hahn’s ‘assistant’ (Mitarbeiterin) is something she felt showed a lack of professional recognition; she also protested against this label in a letter to Otto Hahn. Her 1963 lecture at the Urania Adult Education Centre in Vienna on ‘50 Years of Physics’ formed the basis for her only autobiographical work, a short article published in 1964 in English under the title Looking Back.

“Publications described her as a ‘trailblazer’ who, as a female scientist, had fought ‘for parity with world-famous male colleagues’ and ‘a place of honour in the field of physics research’.”

In 1947, Meitner’s native city of Vienna awarded her the Prize for Science and Art. When her doctoral diploma was renewed at the University of Vienna in 1956, Erwin Schrödinger’s commendation highlighted her services in taking ”Austrian talent […] into the world”. On the occasion of her 80th birthday in 1958, publications described her as a ‘trailblazer’ who, as a female scientist, had fought “for parity with world-famous male colleagues” and “a place of honour in the field of physics research”. In 1957 she received one of the most important German orders of merit, the Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts. The Republic of Austria awarded her the Order of Merit for Science and Art 1st Class in 1967, one year before her death. In this case too she was the first woman to receive what is the highest honour of the Republic of Austria.

Overall, Lise Meitner received a total of around 20 national and international awards (including five honorary doctorates). After her death, the Austrian Arbeiterzeitung newspaper published an obituary bearing the title ‘Austria’s Madame Curie’, which ended with the conclusion that “this small, retiring scholar” had “indeed, like Madame Curie, proved that women can achieve significant things in the arena of the natural sciences”. The Neue Illustrierte Wochenschau reported on the “death of a great Austrian” and the Süddeutsche Zeitung spoke of the passing of a “Pioneer of the Atomic Age”. The physicist Berta Karlik, for her part the first women to be elected a full member of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW) in 1973, wrote an obituary in the newspaper Die Presse and an extensive article for the Almanach of the ÖAW. In 1970, Meitner’s nephew Frisch wrote an obituary for the Royal Society.

The first biography of Meitner was published just one year after her death, written by Elisabeth Crawford. More scientific articles appeared on the anniversary of her 100th birthday, emphasising Meitner’s significant contribution to the development of nuclear fission, including one by the historian of science Fritz Krafft. Walter Gerlach, a professor of experimental physics at the University of Munich, praised the achievements of Meitner, Hahn and Straßmann and attributed the “discovery of nuclear fission” to Hahn and Straßmann and the explanation of the huge energy release of the nuclear fission process to Meitner and Frisch.

A set of Austrian stamps was dedicated to Meitner in 1978 and, ten years later, she was one of the women included in a permanent series of stamps featuring ‘Women in German History’. In 1978, a ceremony took place at the ÖAW marking 100 years since the births of Hahn, Meitner and Max von Laue. At the time, the daily newspaper Die Presse wrote that “only the Nobel Prize” had eluded her,while the number of her academic honours exceeded “pretty much all the relevant prizes and honours awarded to other nuclear physicists”. In 1997 her scientific fame was immortalised when a newly-discovered element with the atomic number 109 in the periodic table was named Meitnerium.

In 1986 the science journalist Charlotte Kerner published the first German language biography of Meitner, which was awarded the German Youth Literature Prize in 1987. In the 1990s, two extensive monographs on Meitner’s life and work by the historians Ruth Sime and Patricia Rife were published independently of one another. In 2002 a German-language biography by the science historians Lore Sexl and Anne Hardy appeared.

Lise Meitner has also become a research topic in women’s and gender history. Particular interest has focused on the hotly debated question of whether the fact of her gender provides the central explanation for her failure to be awarded a Nobel Prize. This debate led to the formulation of the ‘Matilda Effect’, as described above. Recent research such as the 2018 biography Lise Meitner. Pionierin des Atomzeitalters (‘Lise Meitner. Pioneer of the Nuclear Age’) by David Rennert and Tanja Traxler also expand on this perspective by including the personal aspects of decision making within the Nobel Prize committee.

Since the turn of the century, initiatives to anchor Lise Meitner more firmly in public awareness have multiplied. In 2003 the Berlin State Library staged an exhibition to mark the 125th anniversary of her birth and in July 2010, the Humboldt University in Berlin put up a commemorative plaque to her and unveiled a statue in its Ehrenhof courtyard four years later. The University of Vienna also honoured her – albeit as late as 2016 – with a statue in its Arkadenhof courtyard. In Vienna, plaques commemorate her life on the house where she was born and at the Akademisches Gymnasium high school, and a street in Vienna’s 22nd district is named after her. Schools and streets in many other cities bear her name. Since 2008 the German Physics Society and the Austrian Physics Society have both organised annual Lise Meitner Lectures. The Lise Meitner Prize for nuclear physics at the Humboldt University is named after her, likewise an Excellence Programme of the Max Planck Society established in 2018 to target, attract and promote ‘exceptionally qualified women scientists’. In addition, a funding programme to bring foreign scientists (men and women) to Austria carries her name.

Lise Meitner’s prominence has also been increased by representations in popular media. One example is the docudrama with the questionable title Mutter der Atombombe (‘Mother of the Atom Bomb’), first shown on 6 August 2015 on the anniversary of the US bomb dropped on Hiroshima. In interviews with Charlotte Kerner, Ruth Sime and Hahn’s nephew Dietrich Hahn, amongst others, Meitner is ascribed a decisive role in the discovery of nuclear fission. In the older, better known film Das Ende der Unschuld (‘The End of Innocence’), made in 1991, she makes only a short appearance, predominantly in connection with her flight from Germany. The actual plot revolves around the ten scientists interned at Farm Hall in 1945 and the race to build the first atom bomb, in which she played no actual part.

There is a certain tragedy in the link between her name and the development of the atom bomb. While it makes her more well known, it does not do her justice either as a scientist or as a human being. More fitting is the inscription on her gravestone in the English village of Bramley, which was chosen by her nephew Frisch: “A physicist who never lost her humanity”.

Translated from German to English by Joanna White.

Learn more in this title from De Gruyter

[Title Image via Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain]