Iconoclasm: From Post-Socialist Yugoslavia to Black Lives Matter

Against the backdrop of the ongoing protests across the United States and Europe to denounce structural racism, take down its monuments, and call for a critical postcolonial confrontation with history, Gal Kirn draws connections between the present moment and the memory culture of the new states of former Yugoslavia during the 1990s.

From the 1990s onwards, Partisan and socialist monuments in the former Eastern Bloc have been systematically removed or overhauled. In the last part of my book The Partisan Counter-Archive, I focus on how this was done, by whom, and for what reasons. The process of revisiting and altering monuments to the past is a kind of historical revisionism. The revisionism targeting Partisan and socialist monuments is arguably underpinned by right-wing ideas.

Yet the recent toppling of monuments standing in the epicentres of colonialism and slavery in the US, the UK, and across Europe has also been viewed as a new form of historical revisionism. The way the Black Lives Matter movement challenges monuments to racism and colonial oppression can thus be seen in the same context as the memorial iconoclasm observed in postsocialist societies, despite it being motivated by ideas on the opposite end of the political spectrum. Indeed, conservative politicians and right-leaning historians have likened the campaigns to remove statues of colonialist figures in the wake of the George Floyd protests to mob looting; they accuse protesters of committing violent actions against not only public order and property, but also long-standing traditions and monumental legacy.

As a scholar of Partisan, socialist, and postsocialist transitions focusing on the postsocialist cleansing of memory, I would like to compare these two seemingly unrelated historical moments, the postsocialist memorial revisionism in former Yugoslavian territories in the 1990s on the one hand, and the iconoclasm of the Black Lives Matter movement on the other.

Postsocialist Logic: Demonise the Partisan and Socialist Past, Bid on National Glory

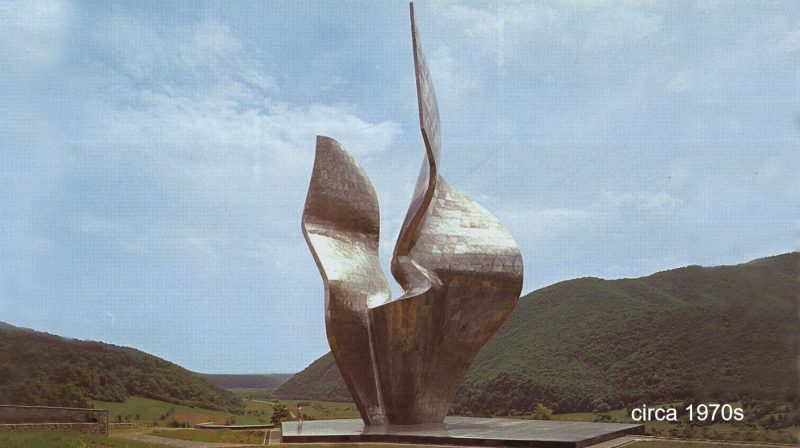

Postsocialist memorial revisionism was supposedly the ‘end of history’; it imposed an implicitly capitalist ‘one nation in one state’ model across the former Eastern Bloc. The dissolution of the socialist states in the 1990s was supposed to be a smooth transition by clearly defined agents and with a clear goal, a transition that brought history to its completion. The fact that the newly formed former Yugoslav states with their democratically elected governments waged such brutal wars during the 1990s quickly belied this narrative. The abandonment of the long-standing and nurtured collective memory of Partisan struggles in former Yugoslavia further undermined the teleological historical narrative: the Partisan tradition was seemingly forgotten overnight and any association with it demonised. Many of its remaining artefacts were vandalised or completely destroyed.

“Any visible resistance to the changes made by the nationalists was deemed ‘Yugonostalgic’.”

There was a widespread perception in the 1990s that the Partisan struggle was the founding myth and the cornerstone of the ostensibly totalitarian Yugoslav dictatorship. The former holy trinity of Partisans, socialism, and Marxism with the image of Tito’s ghost above them became the axis of evil during the 1990s. For their nationalist opponents, it was not enough to declare the Partisan movement and its successors a failure; they wanted it buried for good in the dustbin of history. State and municipal powers, vandals, curators, and new historians took it upon themselves to reshape the new memorial landscape of former Yugoslavia, organising the removal of monuments and orchestrating the erasure of public memory. Any visible resistance to the changes made by the nationalists was deemed ‘Yugonostalgic’, an expression of sympathy with the defunct socialist regime.

The intensified feelings of national pride and ethnic hatred in the new states hinged on the state-led revisionist attempts to overwrite collective memory discourses. At the same time, the ‘primitive accumulation of capital’ (Marx 1990) by the political elites emerging in the new states brought an end to the collective ownership of the means of production that had been the hallmark of Yugoslavian socialism. In other words, the new nationalists’ privatisation of the means of production paradoxically brought about their denationalisation. Suddenly deprived of the material basis of their livelihoods, the people of former Yugoslavia also lost the material basis of their national pride. In the Marxian model of thinking about society, the material and economic means of production determine all other social phenomena (e.g. politics, ideology, and culture). In the civil wars of the 1990s, however, politics cut itself loose from the material preconditions of its existence and paved the way for the new states’ economic transition to neoliberalism.

Yet apart from economic means, the new states also accumulated power over collective memory; they exercised both symbolic and physical violence on the past, destroying Partisan monuments and nipping in the bud any ideas that evoked non-aligned, modernist, Partisan, and socialist times. These practices were so extreme, they ultimately led to the systematic persecution of people that did not comply with the ideas and newly imagined borders of the new nation-states. In the new era, the Partisan legacy was seen as disrupting memories of the past and visions of the future. Yet the new nation-states were not much concerned with speculations about the future; they were more preoccupied with their ‘glorious’ national pasts, claiming their roots in medieval kingdoms and, even further back, Alexander the Great.

“Historical revisionism became a major pillar of the new ideological state apparatuses.”

By steering collective memory in this way, the new states meant not only to provide their people with new national heroes and narratives, but to heal the wounds inflicted on their people during the socialist era: a loss of autonomy, political betrayal, civil wars, occupations. At the same time, the grandiose nationalist memory rhetoric of the new states obscured far less comfortable and less glorious truths about their past, from anti-Semitism to collaborationism during the Second World War. The revisionist culture of memory that emerged in the former East in the 1990s was not limited to academic debates or new museum and archival practices; rather, historical revisionism became a major pillar of the new ideological state apparatuses.

It is worth noting that the socialist official memory centred on Partisan struggles and the anti-fascism of communists and left forces around the world had long been a cornerstone of post-war Europe. The revisionist memory politics of the postsocialist era in the former East was viewed in the West as a turn towards ‘anti-totalitarianism’. The concept of totalitarianism used in this context is blurry, co-opting very different practices from the early Soviet Union to Yugoslavia, and drawing comparisons between communism and National Socialism. In the memory political landscape of the 1990s, everything even remotely related to socialism or the Eastern Bloc was labelled ‘totalitarian’. The renationalisation of official memory that went hand in hand with the de-nationalisation of means of production in the new states was arguably also a kind of totalitarianisation of memory. While national pride was being artificially reconstructed with fantasies of ancient and mediaeval kingdoms, the economy of the new states — that was supposed to deliver the material basis for such national pride — underwent privatisation, causing a sharp increase in class inequalities.

In the European Union we tend to uncritically celebrate Europe as a place of freedom and democracy and view the totalitarian regimes of National Socialism and communism as historical deviations. Colonialism, imperialism, and the prolonged history of fascism, from early-1920s Italy to Spain and Portugal in the mid-1970s, seem to be absent both from the collective memory of Europeans and the official memory politics of the European Union.

The revisionist memory politics of the postsocialist East has a strong performative element, and its performances often seem to be meant for Western eyes. The removal of prominent symbols of communist power, which was epitomised in the fall of the Berlin Wall and the demolition of iconic monuments on public squares in the former East, testifies to this performative tendency. Major Marx and Lenin busts, Partisan memorials, statues of Soviet soldiers or socialist and working class leaders were all torn down in a provocative display of irreverence towards all that was sacred under communism.

Many of these demolitions were glaring acts of grassroots vandalism, others hushed overnight removals led by the state or local authorities. The old monuments were either buried in secret locations in nearby woods, or put in museums or depots, waiting to be possibly put back on display in the future (as many were in reunified Germany).

Such monumental cleansings destroyed the symbols of a transnationalist, egalitarian, and universalist emancipatory past, of working-class and antifascist struggles, and of movements fighting inequality on all fronts. For even though socialism undeniably failed, we need to concede that its emancipatory promise and the many historical personalities and movements that fought for collective emancipation in its name should not be simply dismissed out of hand, because doing creates a dangerous vacuum. Tellingly, the Partisan and socialist monuments removed in the 1990s were replaced in many formerly Eastern countries with revisionist monuments of nationalists or even local fascist collaborators (see a small map of selected revisionist monuments that I made in cooperation with Fokus Grupa.)

After the collapse of socialism, the West turned to the last strongholds of ‘despotic’ dictatorships, staging ostensibly humanist interventions in ‘rogue states’. These involved the toppling of both the living leaders of these states and their monuments, both the subjects and the symbols of power, including Saddam Hussein in 2003 and Muammar Gaddafi in 2011. US Americans and Europeans thus sought to establish the universal primacy of their ‘civilization’: they claimed to be spreading freedom and peace while liberating peoples from the yoke of ‘totalitarianism’. Ministries of culture became the gatekeepers of public memory, casting the ‘evil’ wrongdoers of the old regimes as figures in a cautionary tale and nostalgically appropriating elements of a ‘pre-totalitarian’ past. Well into the first decades of the twenty-first century, the developed West continued to reign supreme, as countries in the developing world struggled to catch up with the universalised Western model of modernity.

It is, of course, unwise to romanticise the fallen leaders of the past, or lament the extinction of real existing socialism. But we need to face the triumphalism of Western capitalist democracies with a healthy dose of scepticism, or we risk flattening history and missing the emancipatory potential that the lessons of history carry for the future. This is rendered easier by the fact that the US American and European capitalist order that imposed itself around the world in the period after 1989 has been shaken in more recent years, first by the financial crisis of 2008, and now, even more drastically, by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Cutting the Head off ‘the End of History’: The BLM Movement’s Desire for Justice

The postsocialist era played an important role in cementing the triumph of neoliberal capitalism, the order that brought forth phenomena such as Trump and his ‘Make America great again’ campaign. Yet the fall of socialism and its ideological erasure coincided with another ideological shift that worked in the opposite direction, increasingly destabilising the established Western capitalist order: decolonisation and the liberation movements in the US.

The anti-racist Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement that resurfaced with new force in the wake of the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 must be seen as the most recent manifestation of emancipatory ideologies that have been around in critical theory, politics, and culture for decades, and that fundamentally run counter to the spirit of reckless capitalism. Though the BLM movement emerged in reaction to some tenaciously racist practices of the US police force and justice system, BLM activists not only continue to be exposed to police violence, but are also subject to ideological attacks for the perceived iconoclasm of their recent demands for the removal of statues commemorating imperialist and colonialist figures. Their critics view such removals as acts of looting and vandalism that cannot right the wrongs of history. Unlike these critics, I would argue that, within a very short period of time, these removals succeeded in articulating a break from the defeatist postsocialist attitude that viewed in Western capitalism an ‘end of history’ without any alternatives.

“The statues whose removal BLM activists are campaigning for are often effectively monuments to slave masters and perpetrators of genocide.”

The anti-racist movement has become increasingly vocal in its demands in recent weeks and has spread from the US to Europe and beyond, exposing the tenacity of structural racism and the disproportionate use of police violence against Black people and people of colour even outside the US. It lays bare one of the Western liberal democracies’ best-kept secret: their origins in a profoundly racist and exploitative colonialist order.

European and US American official policies, monuments, museums, and textbooks still fall short of recognising the reality of Western colonialism. The statues whose removal BLM activists are campaigning for are often effectively monuments to slave masters and perpetrators of genocide. For centuries, these figures have stayed firmly in place, inscribed not only on public spaces across the US and Europe, but also lodged in people’s memories. Ironically, while the then-new capitalist order expulsed Partisan and socialist monuments with tremendous haste in the postsocialist East, it left monuments to its own crimes standing as a matter of course, arrogantly defending them as part of its ‘tradition’ (see also Enzo Traverso).

Yet the anti-racist movement does not simply call for the removal of figures of oppression in order to create a more politically correct visual landscape. Rather, it calls for a new radical justice system to replace the profoundly dysfunctional trinity of military, police, and prisons described so well by Ruth Wilson Gilmore in Golden Gulag already back in 2007. The toppling of monuments to racist and oppressive figures is probably the most spectacular and iconoclastic visual marker of this new idea of justice. It also highlights the popular power and strength of the BLM movement and points to a shift towards a ‘multidirectional memory’ of slavery, colonialism, and the continued curtailing of rights of racialised minorities (see Michael Rothberg).

The discourse on ‘the end of history’ that started in 1989, as well as what might be called a real end of memory, can be mapped against the liberation movements culminating in BLM. Doing so helps us see how revisiting narratives of history and memory can open up the possibility of a radically different future, a possibility known to all revolutionary movements of the twentieth century. Ignoring this knowledge, turning a blind eye to the necessity of confronting a history of oppression, and clinging instead to a tradition built on it is not merely reactionary; it is wrong. Marx believed that the scope of our actions is determined by our social circumstances, but that collectively, we can in turn influence these circumstances. By inventing new ways of remembering past injustices and oppression, and adding to the momentum of the anti-racist movement, we can lay the groundwork for social justice.

The plinths of toppled statues should be left empty, as reminders of the important battles waged against the legacy of the oppressors. Attempts to repurpose them, as one incident in Bristol in July 2020 showed, come with their own difficulties. After the statue of Edward Colston, a merchant implicated in the Atlantic slave trade, was removed from the city centre, (white) artist Marc Quinn used the empty plinth to surreptitiously mount, overnight, a statue of BLM protester Jen Reid. The Bristol City Council removed the statue a day after it was erected, to mixed responses from the public. But the incident proved the impact of grassroots activism and the role of critical thought in shaping new commemorative cultures within communities and in individual minds.

The task for those of us who work on the subjects of Partisan, anticolonial, and emancipatory narratives of the past is to get involved in the struggle, and contribute to it with some modest proposals. My book The Partisan Counter-Archive is an attempt to do so. It commemorates the voices of those oppressed, occupied, and exploited in the past and present while at the same time safeguarding these voices and the gestures and images that accompanied them for an emancipated future.

“We have been listening, looking at, reading, and experiencing the side of the perpetrator, oppressor, and coloniser for way too long.”

We should never again buy into the narrative of the ‘neutral mediator’ that respects and listens to all sides and drives reconciliation. We have been listening, looking at, reading, and experiencing the side of the perpetrator, oppressor, and coloniser for way too long. Those from postsocialist and in particularly from post-Yugoslav regions saw the protagonists of Partisan and antifascist struggles displaced from public memory and official history by fascist collaborators. History is neither a closed nor a linear process, but one that is perpetually open and full of breaks and interruptions.

The removal of names and statues will not, in itself, automatically herald a new, more just and egalitarian society. But it does express, symbolically, a wish for justice and equality, for a new world that is on the side of the oppressed.

Learn more in this related title from De Gruyter

[Title Image by Chris Henry via Unsplash]