How De Gruyter Is Making Its eBooks More Accessible

Not everyone experiences reading the same way. To ensure that people with visual impairments can access the same information as everybody else, we set up a dedicated working group at De Gruyter to improve the accessibility of our content. We spoke to three of its members about the challenges and achievements of the past year.

With deeply nested sentences, intricate graphics, and page-long tables, reading an academic publication already requires serious cognitive effort. Now imagine that essential chunks of information you need for your research work are missing, like pieces cut from a library book. This scenario is the reality for many visually impaired readers who rely on assistive technologies to gather and access online literature.

Thankfully, in an evolving world that places greater emphasis on inclusion, the onus to meet accessibility standards is increasingly a legal requirement too. As a knowledge facilitator, it is only natural for us at De Gruyter to respond to these changes. To ensure our eBooks are accessible to all by mid-2025, we established an accessibility working group whose members have been anything but idle this past year.

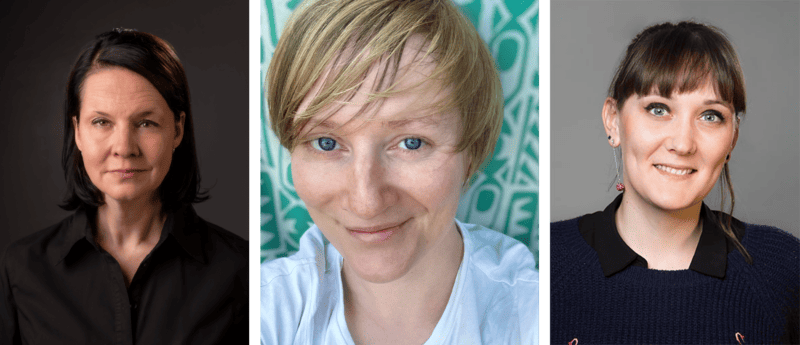

For insights into the challenges of accessible publishing and the advances made so far, Alexandra Hinz talked to Bettina Algieri (Content & Production Editor Books), Franziska Bühring (Director Data Standards & Processes), and Gabrielle Cornefert (Acquisitions and Content Editor Books), all of whom have been part of the working group since its formation.

Alexandra Hinz: Why is accessible publishing important?

Bettina Algieri: The European Accessibility Act makes it mandatory that from June 2025 all eBook publications, with some exceptions, must be accessible for persons with visual impairments. Barriers to reading affect a large group of people. In Germany, for example, there are officially around 1 million visually impaired people, but this number doesn’t include people with macular degeneration, glaucoma, or diabetes-related eye diseases. Taking them into account, the total rises to more than 10 million. Fortunately, we are now at a point where societies are working hard to pass legislation to ensure more people have access to reading.

Alexandra Hinz: What makes an eBook accessible? And how are traditional eBooks not as accessible as they should be?

Gabrielle Cornefert: When it comes to written books, accessibility essentially means that publications can be read aloud to users by assistive technologies. The challenge is to transcribe every visual element on the page in a way that enables screen readers to represent it in spoken form. It’s quite easy to do this with regular text, but it gets much more difficult when we’re dealing with charts, graphs, photographs, etc.

Learn more about alt text in our blog post “Image Alt Text: How to Make Your Scientific Publication More Accessible”.

Franziska Bühring: Exactly. Visual content cannot be accessed by non-visual readers. So, what’s needed is alt-text, or alternative descriptions for images. Currently, our eBooks are to a large extent already accessible, but images are the major exception at this point.

Alexandra Hinz: How far is De Gruyter with making its eBooks accessible?

Bettina Algieri: For nearly a year, we have been working as part of a task force to inform our colleagues on how to make eBooks accessible. We have already launched an accessibility FAQ, and we recently completed an author guide on how to prepare accessible manuscripts. The next steps are compiling technical guidelines and adapting internal workflows to achieve our accessibility goals.

Franziska Bühring: We are currently evaluating whether we can fully integrate the additional requirements for accessible publications into our existing workflows, or whether we need additional services or vendors to assist us in the production of accessible eBooks.

“Accessibility requirements impact the entire value chain from the acquisition of book projects to manuscript preparation and book production.”

Gabrielle Cornefert: Accessibility requirements impact the entire value chain, from the acquisition of book projects ‒ the conceptual stage ‒ to manuscript preparation and book production. Especially during manuscript preparation, we need to involve our authors, because they know exactly how text and figures interact within their book, what information figures are meant to convey, and how that information can be presented to best ensure accessibility. It’s going to require a huge operation and a lot of teamwork.

Alexandra Hinz: Have you received any input or feedback from users with reading disabilities?

Gabrielle Cornefert: Yes, we have. As sighted persons, we only have an abstract conception of what it means to use assistive technologies for research. In order to think through our accessibility workflows, we needed input from academics who rely on these technologies on a daily basis. Luckily, some of our visually impaired authors agreed to share their experiences with us. Despite time constraints ‒ visual impairments, as with other disabilities, tend to put additional strain on already packed academic schedules ‒ they were enthusiastic about our project and very happy to help. They provided key insights into their research process using assistive devices, the evolution of technology they have witnessed since starting their careers, and their strategies for coping with non- or poorly accessible research.

Alexandra Hinz: What are some of the challenges you’ve encountered along the way?

Bettina Algieri: At the beginning, one of the biggest challenges for our working group was that we didn’t have enough information to go on yet. Germany’s implementation of the European Accessibility Act – the Barrierefreiheitsstärkungsgesetz – still lacked detailed wording and specifications. We were therefore constantly trying to gather new information. We consulted the Börsenverein, the dzb lesen (the German Center for Accessible Reading), and also international organizations like the Daisy Consortium or the Italian LIA Foundation. This research cost us half a year, for sure.

Franziska Bühring: Another challenge is that we publish a wide variety of content. There are certain content types that are extremely difficult to transcribe into an accessible format. While linear books can be read aloud from start to finish, there are certain types of content, critical editions or art books for example, for which a linear format is just not applicable. The extent to which these titles can be made accessible will necessarily be limited. That’s one of the things we’ll need to figure out as we go.

Alexandra Hinz: So far, we’ve only talked about books, but are there also similar plans for other publication formats like journal manuscripts?

Gabrielle Cornefert: Absolutely. While the European Accessibility Act is not directly concerned with journals, it’s our aim to include as many products as possible.

Franziska Bühring: In the accessibility working group, there’s also a colleague from the journals team who will try to extend the approach to journals and integrate accessibility considerations in the manuscript guidelines. Though they lack the legal obligation, they will try to implement this as much as possible.

“Our vision is that accessibility should be a matter of course, rather than a challenge to overcome.”

Bettina Algieri: Our vision is that accessibility should be a matter of course, rather than a challenge to overcome. So, adopting an approach that makes a wide variety of publications accessible is essential.

Alexandra Hinz: What advice would you give to publishing professionals who might be just starting to prioritize accessibility in their publications?

Gabrielle Cornefert: Regardless of the size and structure of the organization, the idea is to identify the stages of the value chain where questions of accessibility can be tackled most efficiently, and then to involve the relevant people. Accessibility might at first seem like a technical aspect of eBook production ‒ which it is, strictly speaking ‒ but we found that involving editorial teams and authors long before production starts was key to providing high-quality accessibility.

This is why we prioritized the creation of author guidelines for accessible manuscript preparation. They’re free for everybody to consult and we expect a great exchange of best practices in the coming years ‒ what works, what doesn’t work. We’ve done our best to provide detailed guidance and as many examples as possible with the information available to date, but it is quite possible, for example, that assistive technologies will improve and make some of our recommendations outdated.

We look forward to participating to that conversation in the coming years, and I believe all our colleagues in the publishing industry feel that way too.

Bettina Algieri: One piece of advice we could give to other publishing professionals is that it’s better to be partially accessible than not accessible at all. It’s about a real will to produce accessible eBooks.

Alexandra Hinz: How do you see the future of accessible publishing evolving?

Gabrielle Cornefert: The future will be more and more accessible, that’s for sure ‒ and that’s excellent news for the research community as a whole. One of the authors we hired to learn more about assistive technologies told us what it was like 15‒20 years ago, when screen readers were at a very basic stage of development and things were much, much more complicated for visually impaired researchers. In the last decade, these technologies have already improved quite dramatically.

“We hope to see a shift in how researchers produce their own work with accessibility in mind.”

In the years to come, we might see more than just assistive technology itself or accessible eBook formats evolving. In addition, we hope to see a shift in how researchers produce their own work with accessibility in mind. For example, rather than crafting a very complex chart combining text, numbers, numerous shapes, and colors, an author might choose to present their data through a series of simple, monochrome charts that can be easily described by alternative texts. Obviously, elaborate data visualization always conveys a certain “wow effect” on the page of a book. But it might not serve a visually impaired readership, who will have to listen to extremely long, and possibly confusing, audio descriptions of the complex visual content.

So, the way people think about data presentation might evolve. We believe it can be a real win for research in general to have that kind of structure and clarity.

Bettina Algieri: In the future, we might even receive better structured and prepared manuscripts because of accessibility requirements, so it could be a plus for us, too.

Alexandra Hinz: Thank you for this insightful conversation!

[Title image by supersizer/E+/Getty Images]