Cognitive Science and Classical Studies: The Chance for a Constructive Dialogue

There's a new and rapidly growing discipline on the block and it's known as cognitive studies. How are its insights into perception, intuition and emotion transforming humanities research? In the case of classics, cognitive approaches have already opened up a world of possibilities.

Cognitive studies is incredibly exciting because it is so multidisciplinary and open to diverse discussions and questions. In the current era of “growing excitement about the brain,” as the American philosopher Alva Noë puts it, there has been a long-standing interest in a dialogue between modern natural science research on human cognition and research in the humanities.

The term ‘cognitive’ is a broad one that refers to the engagement with active mental processing. The traditional understanding of the human mind and behavior in terms of Cartesian dualism has been vigorously challenged in recent years, and it’s been thrilling to see the emergence of some new models for conceptualizing cognition, emotion and behavior which no longer contrast cognition with feelings. It includes perception, intuition and emotion insofar as they are related to how the agent gathers knowledge about the environment and finds their way through it. The incorporation of information from physiology and cognitive processes opens up a whole new world of possibilities when it comes to literature, language, material culture, performance and religion.

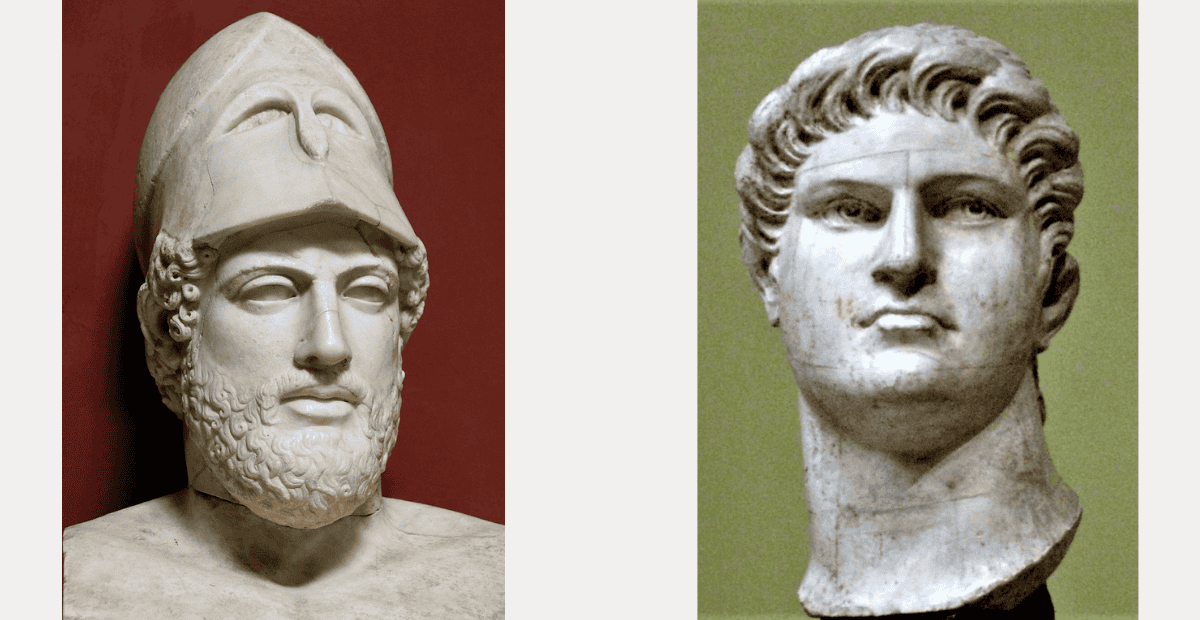

The humanities, and ancient studies in particular, are a way for neuroscientists and experimentalists to gain important insights into the structure and function of the nervous system and brain. Just think for a moment about the insights we could gain by studying the lifestyle, ways of behaving and talking, and responses to emotional crises in Nero’s Rome, or in classical Athens during the time of Pericles. By comparing these patterns with our own society, we can gain some inspiring insights that will be of benefit to both classicists and experimentalists alike.

Embodied, Embedded, Enacted, Extended

The nineteenth century saw an explosion of interest in mechanisms in science, leading to some fascinating questions being raised about the body-mind relationship. As machines became more involved in decision-making and problem-solving, it seemed that these challenges were becoming more prevalent – and that was just the beginning. Interest in this line of enquiry grew significantly during the post-World War II boom of computational progress, when it was all the rage in the so-called ‘first wave’ of cognitive studies, and then later in the second wave, which postulated that our mental processes are linked to biological and physiological phenomena as well as cultural practices.

Described as distributed cognition, this approach provides a framework and method for studying human-object interactions in a way that is both fascinating and innovative. It’s all about how cognition extends into the environment through a mix of social means and technology. In the philosophy of mind, there are various theories of the embodiment of the mind – some overlapping, some diverging – to which distributed cognition is closely related. These are the four Es of the 4E Cognition paradigm (Embodied, Embedded, Enacted, Extended), and together they provide a broad perspective on the interactions between body, mind, emotions and environment.

A Guide to Classics and Cognitive Studies is intended as a stock-taking in various branches of ancient studies – including literary criticism and poetics, linguistics, ancient history and archaeology – to provide an overview of the fruitful collaboration between classics and cognitive studies in recent decades. Four major research areas or perspectives are presented in relation to the ancient world: Material agency and its connection to mind; cognition and the perception of space; imagination, vision and cognitive approaches to seeing; and the ‘sensory turn,’ focusing on experience and experientiality in ancient sources.

And now follows something really special: The fifth chapter is presented in a different medium, consisting of interviews with David Konstan, Angelos Chaniotis and Douglas Cairns. The work of these three incredible pioneers in the study of emotions in the ancient world has had a profound impact on the interplay and dialogue between classical studies and cognitive approaches in recent decades. Emotions are an absolutely essential part of historical and literary studies, and they form a shared fabric for all the above-mentioned thematic complexes.

The interviews were a real treat for anyone interested in the subject matter. Each one took place in the spring of 2023, asking the same or very similar questions, and the reader can enjoy discovering how their answers differ.

This book is just one of many ways to gain a deeper understanding of the situation. It may be not the only or even the best way, but it’s a great place to start! Above all, it is an attempt to take stock of a rapidly evolving and highly controversial field that is currently in full bloom. It contributes to evaluation of the phenomenon and the process that has taken place in classics over the last twenty years. Ancient disciplines are currently undergoing a period of exciting transformation, with many modern theories being applied to ancient material. For cognitive studies, this represents a success, but also an ongoing dialogue; one could suggest with this stocktaking that cognitive studies can and will also benefit from engagement with ancient sources.

Not Everywhere the Same

“Many ancient thinkers took great care to consider the intricate connection between the mind, the body, other people and the environment.”

One of the most fascinating aspects of applying cognitive studies to the ancient world is the question of how relevant our current data are to a society three or two thousand years ago. The last 25 years have seen a revolution in the humanities and ancient studies, with cognitive approaches taking center stage. Richard Nisbett’s many years of work on cross-cultural cognitive studies and his famous statement that “human cognition is not everywhere the same” is just an example of how this new approach is shaking up the way we think about the past.

Human existence is an incredible, complex and multifaceted journey of the brain, the body, other people, the external material world and a wide variety of things and technologies. The ancient ways of thinking that underlie the cognitive artefacts left to us by the ancient Greeks and Romans are a testament to the fact that our ancestors were aware of this incredible connection between the mind, the body, other people, and the environment. Indeed, many ancient thinkers took great care to consider the intricate connection between the mind, the body, other people and the environment.

Embodiment and distributed cognition are two absolutely key concepts that should inform much of what we do as researchers of the ancient world. ‘Cognitive classics’ is a new development that builds on the insights of previous research. The most sustainable interdisciplinary collaborations are based on models and insights that acknowledge the inescapable fact that the mind is embodied.

This is an opportunity to discover just how far interdisciplinary conversations between cognitive and classical studies have come. As Alva Noë points out, consciousness is a truly global phenomenon – and by taking a holistic view of the active life of humans or animals, we can truly understand the incredible contribution the brain makes to conscious experience.

Publishing on December 2, 2024

[Title Image by Jackie Niam/Getty Images]