Catalogue Raisonné as Artwork

In an era of digital catalogues raisonnés, artist Michael Müller has embraced printed opulence with “Ernstes Spiel – Catalogue Raisonné.” Using colors, languages and the interplay of images and texts, the supposed parergon is transformed into a Gesamtkunstwerk in its own right.

This blog post is also available in German language: “Das Werkverzeichnis als Kunstwerk”.

For Wolfgang Beltracchi, the most famous art forger of the recent past, the catalogue raisonné was an invaluable tool: he used these books about notable avant-garde artists of the early 20th century to identify paintings that had once been registered but were now lost and unknown, and reinvented them, i.e., created a new image for them. This led to the emergence of lost artworks, allegedly by Max Ernst, Heinrich Campendonk, Fernand Léger or André Derain, but essentially imitations of classic works, which were initially sold at high prices before being exposed as forgeries by Beltracchi himself.

The catalogue raisonné – also known as a catalogue of works or œuvre catalogue – is also particularly important for the field of art studies in general. There are several terms for this comprehensive list of a person’s œuvre in the form of a reference work, and half of them are French. For good reason.

In the 17th century, Paris took center stage as the cultural capital of the world which – thanks to its seminal academy and exhibition culture – it was to remain for almost 300 years. It was here that the catalogue raisonné became established as an important parergon to the artist’s œuvre, both as a concept and in its material form. Initially, catalogues comprised only written details, primarily indicating the type and location of the signature, title, and date of origin. However, over time they grew to include reproductions (engravings, and later photographs) – if the works had indeed survived.

Catalogues Raisonnés of Contemporary Art

If Beltracchi were still active as a forger, Michael Müller’s catalogue raisonné would be of no use to him. For one thing, this is because Müller is a living artist. Originally, catalogues raisonnés were posthumous monographs on particularly significant artists. Some of the earliest examples are catalogues raisonnés of works by Raphael, Cranach or Dürer from the early 18th century, which – as guarantors of the authenticity of the paintings recorded there – catered to the increased economic interest of the art trade.

“As contemporary art in particular has now become an object of speculation, catalogues are becoming increasingly relevant as a means of authentication.”

As contemporary art in particular has now become an object of speculation, catalogues are becoming increasingly relevant as a means of authentication. In many cases, the texts and images recorded in these catalogues are so meticulously and comprehensively compiled that they offer no scope for intentions such as those of Beltracchi.

Another reason Müller’s works are comparatively unattractive to forgers is their desirability, which is naturally less than that of old masters such as Max Ernst or similar artists. The fact that Cubist, Expressionist and Surrealist paintings and sculptures have frequently changed hands, have a long exhibition history, and are mentioned in numerous texts is generally indicated in the relevant catalogues raisonnés under “provenance,” “exhibitions,” “location,” and “literature.”

The first volumes of Müller’s catalogue raisonné currently list only the provenance of some of the works, most of which are owned by the artist himself. This as yet loose connection between Müller’s œuvre and the presentation forums, discourses, and markets of contemporary art also protects it from imitation.

Back to Materiality

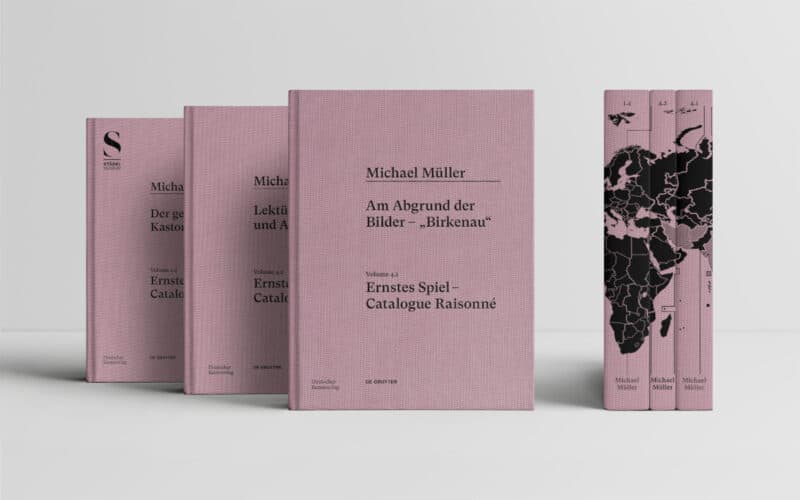

On the other hand, however, it is striking that Müller challenges the reference to tradition and the canon with the very form of his catalogue raisonné. In recent years, it has become common practice to publish catalogues raisonnés exclusively online – not only to save printing costs but also to ensure that they can be continuously and easily updated. By contrast, Müller commissions the production of opulent printed books and, with a total of forty-four individual volumes currently planned, has already surpassed the probably best-known catalogue raisonné, namely Christian Zervos’ catalogue of the works of Pablo Picasso, which comprises thirty-three books in eight slipcases and covers an impressive 114 centimeters of shelf space.

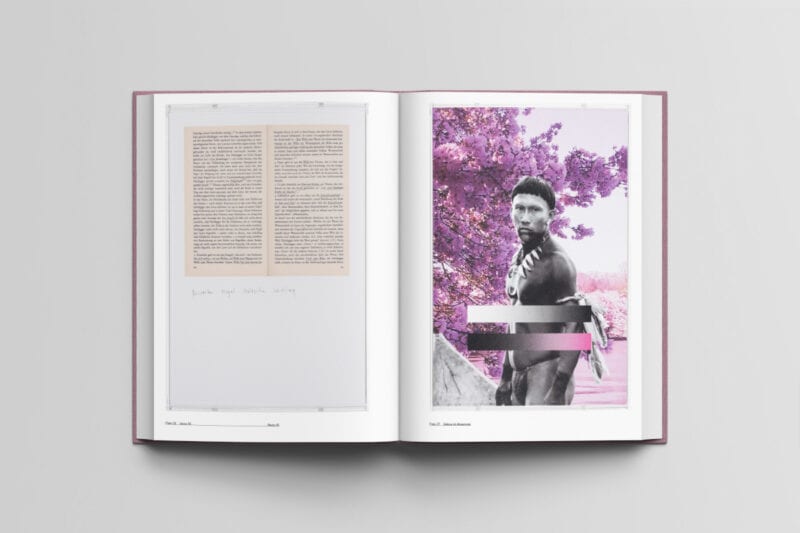

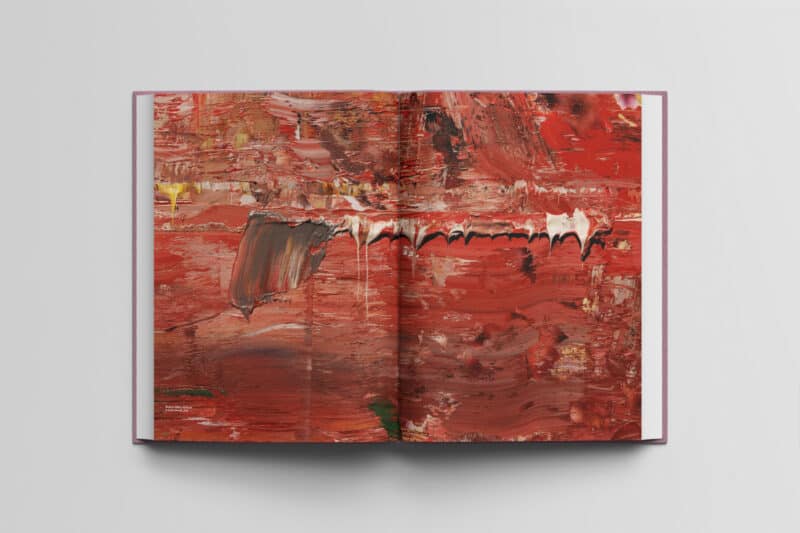

In light of current debates on sustainability, Müller’s approach may seem anachronistic, but this materiality is consistent with his œuvre, as reflected in the books themselves: the dusky rose colors of the linen bindings, the multilingual texts in German, English and Chinese, the relationship between images, text and language, and the penchant for classification and measurement, risk and excess.

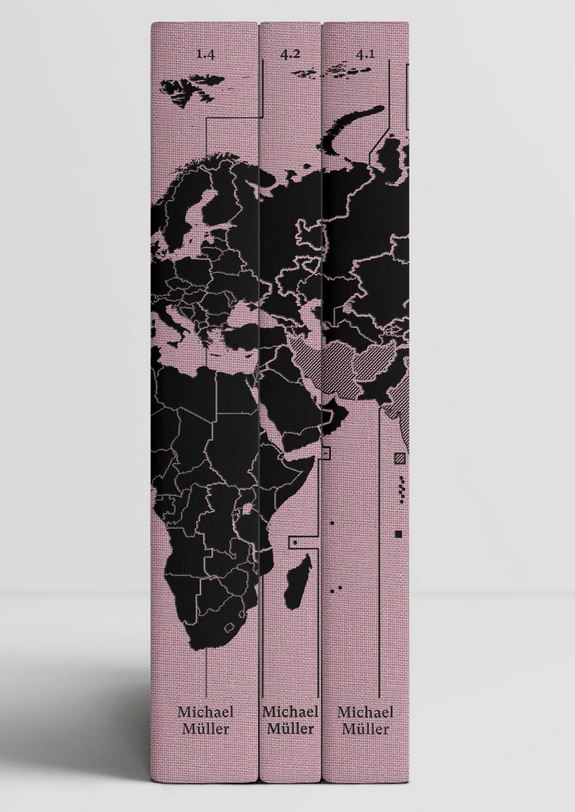

These are all overarching features of Müller’s work to date, whose professional artistic career began with imaginary town and county maps inspired by Asian characters and regions as well as a font titled K4 on pink paper. Accordingly, the spines of the already published books are adorned with individually printed strips of the time zones of a map of the world that will continue to grow.

More Than Just a Parergon

The overall design of Müller’s catalogue raisonné also reflects the concept of expanding his artistic practice of writing, drawing, painting, installations, and performances beyond the medium of the artist’s book. This expansion is echoed in his curatorial and commercial enterprises, whether the initiation and operation of exhibition spaces or the “Alien Athena Foundation,” which funds the catalogue raisonné project as a work in progress. From this perspective, Müller’s “Ernstes Spiel – Catalogue Raisonné” is more than just a parergon: it takes on the qualities of a work of art.

This is compounded by the unusual title: unlike works of art, catalogues raisonnés do not usually have a title, especially not one infused with such poetic significance. “Ernstes Spiel” (“serious game”) is a paradoxical phrase that refers to educational games in a narrower sense and more broadly to the connection between aesthetics and capitalism. This connection is also evident in light of the history and use of catalogues raisonnés described here. While Müller’s “Ernstes Spiel” fulfils the form, function and format of a catalogue of works, it places the catalogue raisonné, with its scholarly and economic gravitas, within artful and, as it were, detached quotation marks.

In light of present-day developments, this status of the catalogue raisonné as a work of art is hardly surprising. On the one hand, a promising market dependency is essentially forcing contemporary artists to contribute to the historiography of their own art and to find ways of archiving their productions and projects, thus offering control. On the other, the expansion of the work via the parergon into a network is a defining feature of contemporary art.

Given the diversity of contemporary art, operating within this network is linked to a desire to modernize outdated notions of sole authorship and authority while still achieving visibility, attention and recognition for oneself. Parerga such as invitation cards, object labels, artist statements or indeed catalogues raisonnés have thus had the potential to become independent works since the conceptual art movement around 1970 at the latest. Furthermore, what is a parergon and what is a work can be a matter of opinion.

[Title image: Excerpt from “Ernstes Spiel”, Vol. 1.4, © Michael Müller]