Apollo’s gift and curse: how music can shape our brain

Performing music at a professional level is probably the most difficult of human accomplishments. It requires the integration of multimodal sensory and motor information and precise monitoring of the performance via auditory feedback.

In the context of classical music, musicians are forced to reproduce highly controlled movements almost perfectly with a high reliability. These specialized sensory-motor skills require extensive training periods over many years. Learning begins at an early age in a playful atmosphere. Routines for stereotyped movements are rehearsed for extended periods of time with gradually increasing degrees of complexity.

Emotion-driven movement

Via auditory feedback, the motor performance is extremely controllable by both, performer and audience. All movements are strongly linked to emotions – pleasure or anxiety – processed by the complex system of nerves and networks in the brain, known as the limbic system.

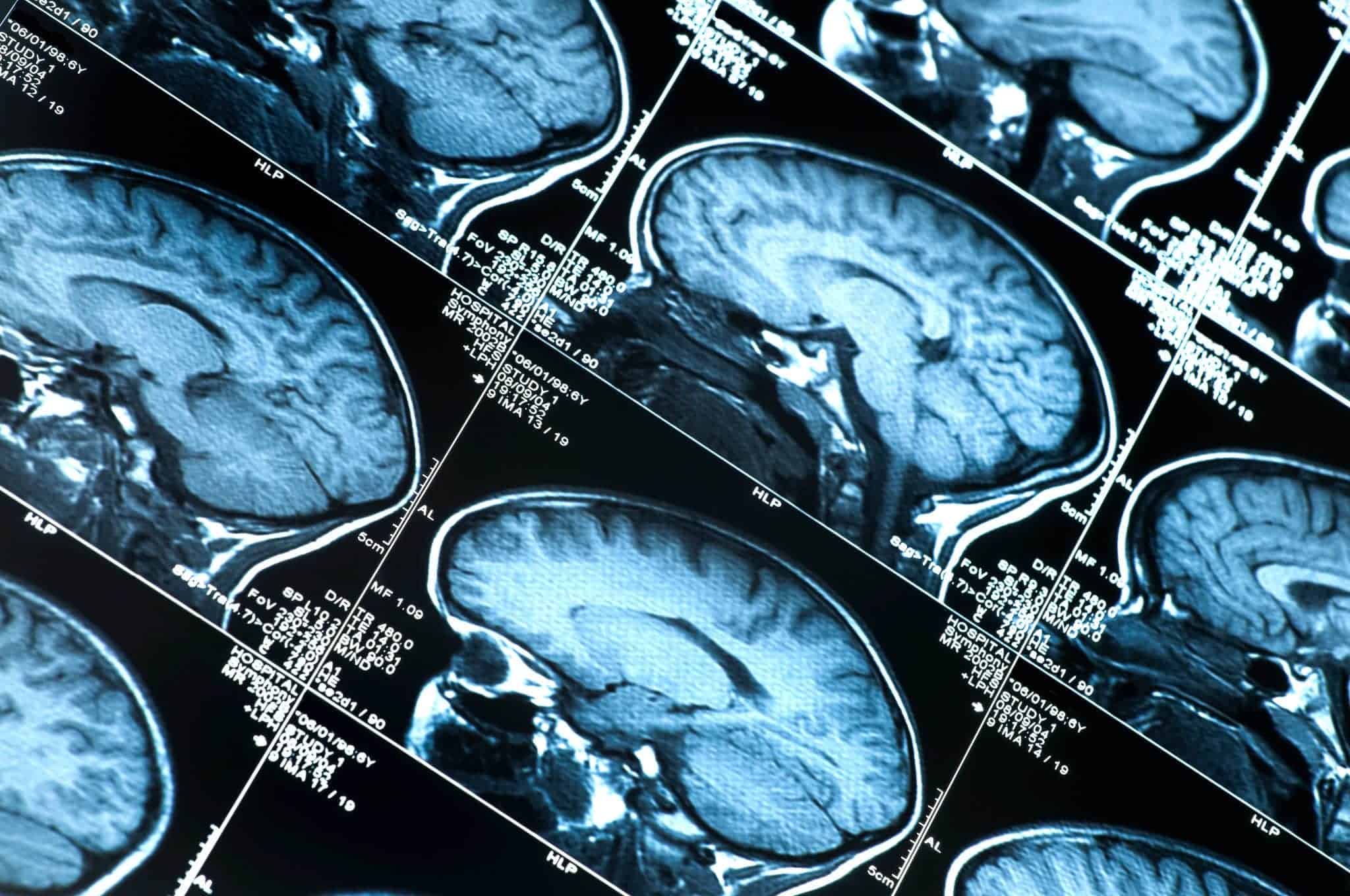

In their article published in Neuroforum, Neurologist Eckart Altenmüller, together with his researcher Shinichi Furuya summarize research on the effects of musical training on brain function, brain connectivity and brain structure.

The authors demonstrate how the superior skills of musicians are mirrored in plastic adaptations of the brain on different time scales. Musical experience induces the formation of functional brain networks after just several minutes, and long term leads to an increase in grey and white matter volume in several brain regions, including sensory-motor and auditory areas, the cerebellum and the anterior portion of the corpus callosum.

“Our research shows, how powerfully music can shape our brain,” explains Altenmüller.

Laying down the foundations for mastership

In recent years, the concept of metaplasticity (activity-dependent changes in neural functions) in motor systems has been strongly supported by first-hand findings. For example, in a recently published study, the authors could show that early training before the age of seven provides a scaffold for later mastership, i.e. for extraordinary sensory motor skills acquired during pre-adolescence and adolescence.

The dark side

Yet, there is also a dark side to the increasing specialisation and prolonged training of modern musicians, namely loss of control and degradation of skilled hand movements, a disorder referred to as musicians’ cramp or musician’s dystonia (MD).

Early training not only provides a scaffold for later expertise, it furthermore renders motor skills more stable than intensive training later in life. This is one of the reasons why degradation of control of skilled movements is five times more frequent in musicians who start to play their instrument later in live.

Neuroimaging studies point to dysfunctional (or maladaptive) neuroplasticity as its cause. Compared to healthy musicians, musicians with dystonia showed, for example, a fusion of the digital representations in the somatosensory (part of the sensory nervous system) cortex. Such a fusion and blurring of receptive fields of the digits may well result in a loss of control, since skilled motor actions are necessarily bound to intact somatosensory feedback input.

Interestingly, the psychopathology of musicians suffering from focal dystonia emphasizes the existence of two different populations based on diverse psycho-behavioural features. Here, the authors speculate that dystonia in musicians could be a maladaptive procedure developed via different circuits of the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamic structures, which mediate movement and emotional drive, between dystonia patients of the first and the second subgroup.

The resulting classification will enrich the diagnostic procedure of MD and will be crucial for the selection of suitable treatment methods.

Read the original article here