The Untold Story of Reformation Women’s Sacred Music

In Luther's times, music expressed the religious experience of enclosed nuns and Anabaptist martyrs, of Calvinist pious wives and Lutheran schoolgirls, of powerful female rulers and tired peasant mothers. Though few of their songs have reached our ears, they make a fascinating narrative worth exploring.

Five hundred years after the Wittenberg theses, the year 2017 is seeing a wealth of discussions and academic research on Luther’s Reformation, its impact on history, religion, society and culture, as well as the ecumenical relationship among the Christian Churches. One particularly interesting aspect of the Reformations – not the most visible, but certainly the most audible one – is their close relationship with music and musicianship.

It is comparatively easy to call to mind the names of the principal Reformers and to study the kinds of music they promoted or discouraged. We may think of Luther, Calvin, Melanchthon, Zwingli or Cranmer, to name a few. In the Catholic field Popes or Cardinals like Carlo Borromeo, saints such as Filippo Neri or Ignatius of Loyola come to mind. We might also choose to focus on great composers of sacred music, such as Palestrina, Lasso, Byrd, Tallis or Victoria.

None of them was a woman.

Rediscovering Female Musicianship

Writing about female musicianship does not mean to segregate it, or to posit its fundamental and intrinsic otherness in comparison to men’s music, or to adhere to the so called female quota ideology. But women’s important contributions to musicianship and sanctity, to artistry and theology in the sixteenth century – in short, women’s voices, often preserved more scantily than those of their male counterparts, might be suffocated unless they receive specific attention.

“As a woman musician and believer, I listen with particular care to the musical experiences of female singers, instrumentalists and composers.”

Moreover, whereas judgements of artistic value based on gender are ridiculous either way, I do believe that there are distinguishing features, proper to the female approach to faith and to music, which can and should be highlighted. As a woman musician and believer, I listen with particular care to the musical experiences of female singers, instrumentalists and composers, who lived as nuns, mothers, wives or unmarried women five centuries before my own life.

Across confessional divides, lay and religious women listened to, practized, and composed sacred and devotional music in unaccompanied singing, polyphony, instrumental performance and accompanied monody. Although the greater part of this artistic world and of this spiritual experience is irrecoverably lost to us, the scanty examples that have survived help us, at least, to imagine and pay homage to it.

Truths, myths and stereotypes

When studying the relationship between women and sacred music in the sixteenth century, there are some truths to be avowed, some stereotypes to problematize or qualify, and some myths to dispel.

Among the undeniable truths we must acknowledge the impressive disproportion in the surviving sources regarding the music of women and that of men, as well as the presence of objective social and religious factors which have caused this situation. Nevertheless, the sixteenth century was also the century when the first collections of sacred music written by women were printed: it was a momentous beginning, and a symptom of a dawning change.

Among the stereotypes to problematize is, for example, the lack of opportunities for professional musicianship for women in the sixteenth century. While this lack was indeed an objective fact, we should keep in mind that choosing one’s occupation freely and depending on one’s talents and inclination was a luxury for most people back then, whether they were women or men.

“Among the myths is the lingering idea that monasteries were oppressive establishments which young women were forced into entering.”

Among the myths is the lingering idea that monasteries were oppressive establishments which young women were forced into entering and where their talents, their femininity and their artistry were mortified. Though, of course, such situations did exist, the picture that emerges from most sources and from many scholarly studies is very different, and portrays thriving realities where creativity, beauty and sincere spirituality could flourish, at least within certain limits.

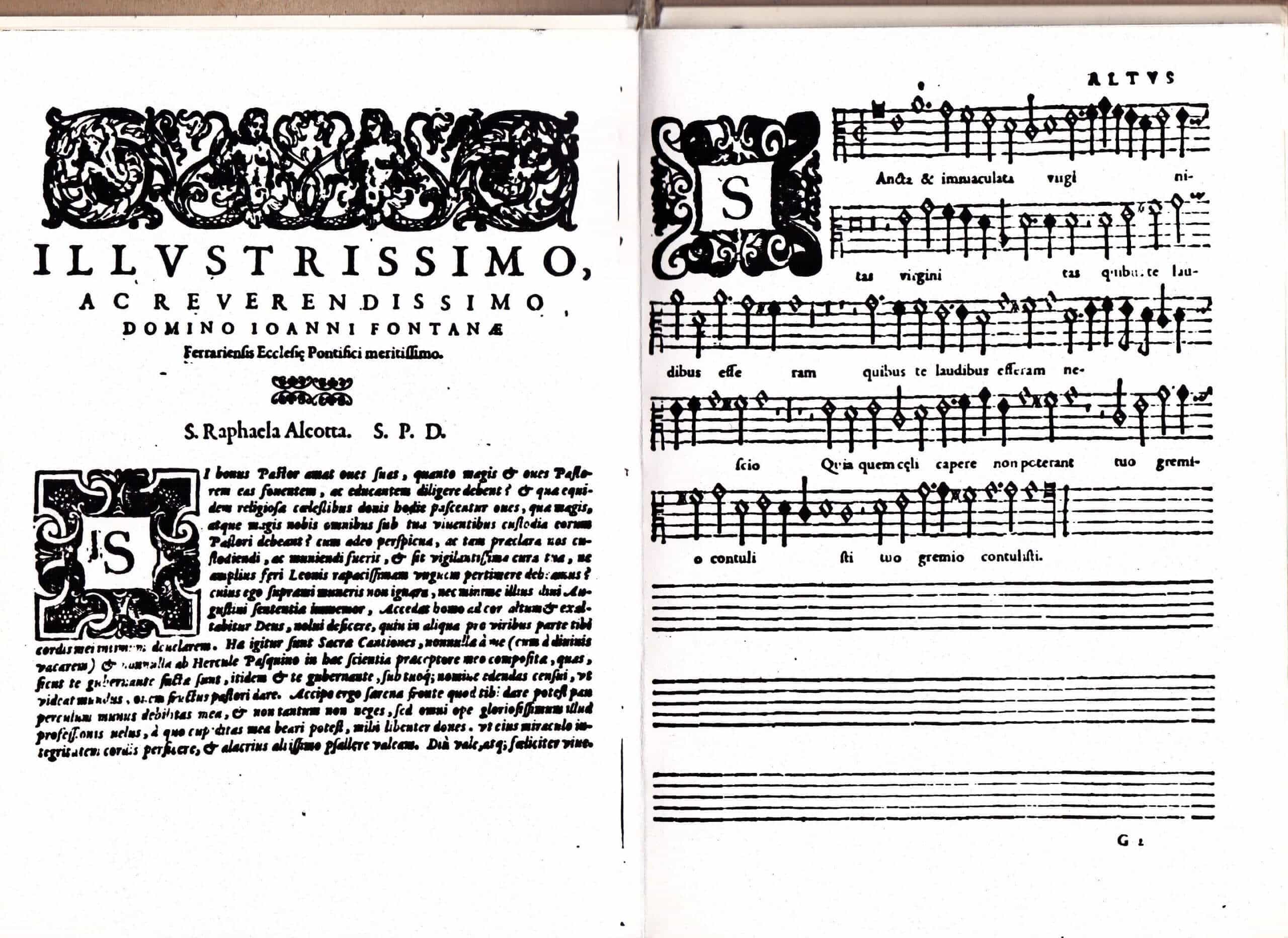

In fact there were women who actively engaged in musical activities linked with the sphere of the sacred. They were professional, amateur, or quasi-professional musicians, aristocratic patronesses, hymnographers such as Elisabeth Cruciger, editors such as Katharina Zell, scribes, publishers and collectors of religious songs, girls whose education included music either institutionally or privately, and nuns such as Raffaella Aleotti.

They lived in cities or on the countryside, and they were women to whom music provided comfort, hope, expression or courage in situations of hardship, persecution or grief.

Frau Musika or Women’s Music?

Martin Luther’s beautiful praise of music, Frau Musika, resembles, in both shape and content, a love song for music personified as a woman.

Music was frequently depicted and symbolized as a woman in this way. It could be embodied by several mythological, religious and historical figures, from the Muses to St. Cecilia. A less common symbol, though a very significant one, is the Gospel figure of St. Mary Magdalene.

In her case, tradition conflated and identified the portraits of three different female characters of the Gospel with a single woman: Mary the sister of Martha and Lazarus of Bethany, Mary who had been possessed by seven demons and the prostitute who washed Jesus’ feet with her tears. Mary Magdalene had also been the first to see and to talk with the risen Christ, who had asked her to bear witness to his resurrection with the other disciples.

Thus, the fascinating figure of the Magdalene could represent femininity as corruption (the prostitute), as an irrational and obscure force (the demonic possession), but also as mystical love (the Mary who listened to Jesus in contemplation) and as Christ’s chosen one for announcing the main belief of the Christian faith (the witness of his resurrection).

Though no mention is made of music in connection with any of the Gospel’s Marys, traditional iconography has frequently associated the Magdalene (especially as a prostitute) with music. For example, the so-called Master of the Female Half-Lengths (fl. 1525-1550) depicted Magdalene as a lute-player. However, music could figure in such portrayals either as a positive or a negative symbol, for example indicating the sinful past relinquished by Magdalene the saint.

Thus, the symbolic associations between music and femininity could range from the exaltation of both (also in connection with the sanctifying power ascribed by some to both) to the harshest condemnation and contempt. In either case, both music and femininity were considered in their abstract, general, symbolic and sometimes stereotypical essence.

The reality of female musicianship obviously differed from such abstractions, but was, nevertheless, to some degree conditioned by the frames of mind they revealed. On the one hand, belief in the sanctifying power of music, particularly in association with its feminine characteristics, could encourage religious women to use music as a devotional exercise, for example in monasteries or movements of spiritual reformation. Cardinal Federigo Borromeo promoted music in Milanese monasteries precisely for this reason.

On the other hand, men’s widespread fears of the dangerous power of music, femininity, and their perilous association put limits to women’s musicianship.

Scanty sources

One consequence of the restrictive attitudes towards women’s music is a depressing paucity of historical sources. If many of our evaluations about sixteenth-century music are hopelessly flawed by our impossibility of hearing how it actually sounded, in the case of women’s music, we lack not only the aural evidence, but even the written sources. In most cases, and sadly, the music of sixteenth-century women has been silenced forever.

“In most cases, the music of sixteenth-century women has been silenced forever.”

But the rarity of preserved sources does not mean that women’s music was inferior: music permeated the lives of sixteenth-century women no less than men’s. At least quantitatively, it is safe to assume that women made music as much as men did. However, as far as the documents in our possession suggest, none of the greatest masterpieces of sixteenth-century music were composed by a woman.

There are many explanations for this. First of all, there is the problem of musical literacy, which often represented a degree of knowledge and culture which was higher, more specialized, and thus harder to achieve than general literacy. If, for example, in mid-sixteenth-century England only twenty percent of adult men could sign a document, only five percent of adult women could do the same.

It seems safe to assume that those who were musically literate represented a minority among the minority who could write their own names. So musical literacy was a privilege often combined with a social status above average. Religious factors such as the educational concerns of the Reformers or the opportunities for learning which many nuns could find in a convent were a positive cultural element for many women of the sixteenth century.

The fact that more people could read and write words than music caused a lamentable situation. A comparatively high number of religious hymns and poems by sixteenth-century women like the poetry of Vittoria Colonna or the hymns of the Anabaptist martyrs have been preserved, while written music that can be safely attributed to women is much rarer.

Arguably, many of such lyrics were destined for singing, either on pre-existing tunes whose title or incipit is occasionally specified or on melodies to be created by the author of the verses. The surviving traces of such musical works are, however, minimal.

Of course, many accompanied monodies sung by both women and men in the sixteenth century were largely improvised. The subject of their lyrics could also be a religious topic or a spiritual poem. Since this kind of music could be practised in solitude or in very small groups, it is probable that this was one of the most common forms women used to express their musical creativity.

Social Status

Though the scantiness of written sources is a constant feature of early-modern female musicianship, proportions changed dramatically with the social status of the women under consideration. The female voices of peasant, poor and uneducated women in the cities of the sixteenth century is hardest to perceive today. But singing was an extremely common activity for women belonging to these classes. At work, singing was a much welcome relief that could lessen the fatigue and boredom that came with repetitive tasks.

The informal and spontaneous singing of vernacular religious songs could also bring comfort and hope, and give a spiritual meaning to the hardships which underprivileged women frequently had to endure. One heart-warming anecdote reports that a woman who was suffering from a difficult labour found comfort and, eventually, the strength to give birth to her baby, when she heard a Lutheran chorale hummed by a passing schoolboy in Joachimsthal.

We can imagine that singing was also an important moment in family life. Mothers sang lullabies, many of which had touchingly religious lyrics, and later gave their children the basic religious instruction by teaching them sung prayers or repeating with them the catechism songs.

Though singing is, of course, a form of art itself, we may wonder whether sixteenth-century uneducated women were also composers. Did they create new songs? Did they adapt, modify or combine pre-existing songs?

Arguably yes. But the problem of authorship and preservation in the repertoire of oral tradition is insurmountable. In most cases, the popular songs we know are the result of collective authorship, in which no single composer can be identified, making the traces of female creativity even harder to recognize.

“The popular songs we know are the result of collective authorship, in which no single composer can be identified, making the traces of female creativity even harder to recognize.”

The situation was slightly better for middle-class women, especially if there were professional musicians in their family or a particular interest in music-making. The possibility for women of this class to become, at least, amateur musicians depended also on where they lived, since in certain zones of Europe (such as the Netherlands) it was much more common for girls to play or sing at a good level than in others.

The religious Reformations certainly contributed to the dissemination of some basic musical knowledge among girls, particularly among the Evangelicals. Women of this class might also be actively engaged in music publishing, editing and collecting, for example by creating compilations of religious musical works for private use or for publication.

Naturally, many aristocratic women received musical education, and some reached a considerable degree of proficiency. This was a consequence of the less pressing needs posed by daily life for the wealthy, of the role played by music as a refined pastime, and of the availability of professional musicians in the musical Chapels and courts of the nobility.

Patronesses and Prioresses

It was not infrequent, for noblewomen, to become patronesses of music and musicians, and sometimes to foster the creation of works in genres which were normally neglected by male patrons. In particular, and especially in Italy, noblewomen tended to sponsor secular rather than religious music and the creation of chamber music works for small ensembles.

This situation was related to social issues. The small size of the performing forces matched the idea that a domestic context was the appropriate framework for women’s initiative, and the male preponderance in the field of sacred music corresponded to their prevalence in Church hierarchies.

Queen Elizabeth of England, who was the sponsor of an exceptional chapel performing superb church music, is only the exception which confirms the rule, since she was the Supreme Governor of the Church of England and an extremely powerful civil ruler. She also fostered programs for the improvement of musical education.

Among the Habsburgs, Margaret of Austria (1480-1530) and her niece Maria of Hungary (1505-1558), in their capacity as governors of the Habsburg Netherlands, were the first female members of their family to become patronesses of music at an international level, establishing an excellent musical Chapel and collecting works of the greatest musicians of the time (such as Lasso, whose sacred works Maria particularly cherished).

Among others, the religious beliefs of Elisabeth von Braunschweig-Lüneburg (1510-1558) prompted her composition of spiritual songs, and the musical education received by Louise Juliana of Orange Nassau (1576-1644), William of Orange’s daughter, encouraged her in her efforts to promote psalmody in Heidelberg, at the court of her husband, Frederick IV, Elector Palatine (1574-1610).

While the acknowledged public role of the aristocrats’ wives allowed them a certain degree of independent enterprise, for example in patronage, for many women of the lower classes, including professional singers, marriage could put an end to their public performances, or represent a serious obstacle to their compositional activities. Their possibility to practice music at a high level largely depended on their husbands’ decisions and on the time they could spare from housekeeping and caregiving.

“For many women of the lower classes, including professional singers, marriage could put an end to their public performances.”

Female musicians who entered a convent could have many more possibilities, in this respect, than married women, though, of course, frequently the public appearances of nun musicians were limited (at least visually) and their freedom to perform outside the monastery was minimal. The nuns in Ferrara, Italy, who performed rather regularly, both outside the convent and within it for aristocratic audiences were one exception to this rule.

Clearly, moreover, while musical activities were normally an integral component of what it meant to be a nun, most religious women were not at liberty to dedicate many hours to purely musical practices, since the rhythm of their lives was articulated and regulated so as to include several spiritual and domestic duties, potentially conflicting with artistry.

Nevertheless, the importance of music in the lives of many Catholic nuns also represented a meaningful symbol which acknowledged the intellectual and spiritual role of women. It found expression in their voices and instrumental performances. In certain instances, crowds gathered in the convent churches where some particularly gifted nuns, such as the Milanese Sr. Claudia Sessa, were singing or performing. This was one of the rare opportunities where sixteenth-century women were the only active subject in an artistic and religious field.

The musical communities of nuns performing in some monasteries (which were particularly focused on musical proficiency) were the all-female reality closest to musical chapels. This remained one of the most serious and hindering limitations for women: Since there was no demand for female musicians in chapels, they could not hope for a professional employment in the field of sacred music.

This, in turn, implied that educating a girl in the skills necessary for a church musician was a waste of time and resources, unless she was to become a nun. Moreover, male church musicians acquired compositional abilities through practice, by imitation and apprenticeship, and they could test the aural result of their first compositional attempts with their colleagues. Another problem was that the pitch range of an all-male vocal ensemble was normally self-sufficient, whereas an all-female choir had to employ instruments – when permitted – for the low-pitched parts.

Thus, and in parallel to the fields in which Italian aristocratic patronesses were most active, female composers’ sacred output in composition frequently remained inferior to their secular works, and small-scale or devotional pieces were favoured.

The Impact of the Reformations

If this was a cursory discussion of the musicianship in Catholic monasteries, the history of the religious Reformations intertwined in turn with various aspects of women’s music. On the one hand, where congregational singing was encouraged, introduced and implemented (such as among Lutherans and Calvinists, or in Bucer’s Strasbourg), women had a new and sometimes revolutionary possibility of making themselves heard in church. On the other, leadership was and remained mostly male, with the exception of some smaller confessions, or tended to be reabsorbed by men after some concessions to women had been made.

The religious Reformations, both Catholic and Evangelical, actively fostered the musical education of girls. Following Luther’s letter To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation (1520), which explicitly promoted schooling and education for girls, many Evangelical movements provided children of both sexes with at least some basic knowledge in literacy; music, of course, was never missing from the schoolchildren’s days.

On the other hand, and following the Jesuits’ focus on education and schooling, among Catholics several women consecrated their lives to the cultural and spiritual improvement of girls, and here too music was seen to be a fundamental element of the curriculum.

Notwithstanding this, the Evangelical Reformations also brought the destruction of many monasteries, forcing former nuns to re-enter the world as wives and mothers. These women frequently possessed a degree of literacy and musical accomplishment which was rare among contemporaneous housewives.

At the same time, many Reformers had encouraged mothers and wives to undertake a genuinely pastoral role within their household: Not only, as could be expected, as the first educators of their children, but also with their servants and – with provisos – with their husbands.

There was, however, another side of the coin, represented by the oppositions and conflicts of confessionalization and by the violence it sometimes caused.

At the apex of religious division, in fact, women could risk their lives for their faith. In the repertoire of martyrdom songs there are many fascinating examples of hymns praising the virtues of female martyrs and songs composed by persecuted women. In some instances, musical resistance was virtually the only weapon left to dissident women for expressing their belief and their stance.

artistry and sanctity

The history of female sacred music in the sixteenth century clearly deserves respect, attention, debate and interest, and I hope that my work will stimulate further research and discussion. While a great part of sixteenth century women’s spiritual experience and work is irrecoverably lost, a wealth of stories of artistry and sanctity still remains to be discovered.

Title image: Master of the Female Half-Lengths (fl. circa 1500–1530) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons