Mother’s stress during pregnancy linked to baby’s poor growth and brain development

Pregnancy can be a stressful time, not only for the expecting mother, but also for her unborn child. Research has shown that an excess of maternal stress hormones affects the development of the fetus and can have long-lasting consequences.

By Ying-xue Ding

Because of poor growth in the womb, some newborns come into this world smaller than they should be. When their birth weight is below the 10th percentile for gestational age – they weigh less than 90% of babies that age – health professionals refer to a condition called intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR).

IUGR increases not only the risk for neurodevelopmental abnormalities, but also the incidence of chronic diseases in adulthood, such as obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension.

“Stress hormones” as a predictor of poor fetal growth?

Fetal growth and development are complex processes affected by multiple factors, one of them being maternal stress in pregnancy. According to a recent review in Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation, stress experienced by the expecting mother can result in an imbalance of fetal nutrition supply and demand. How so?

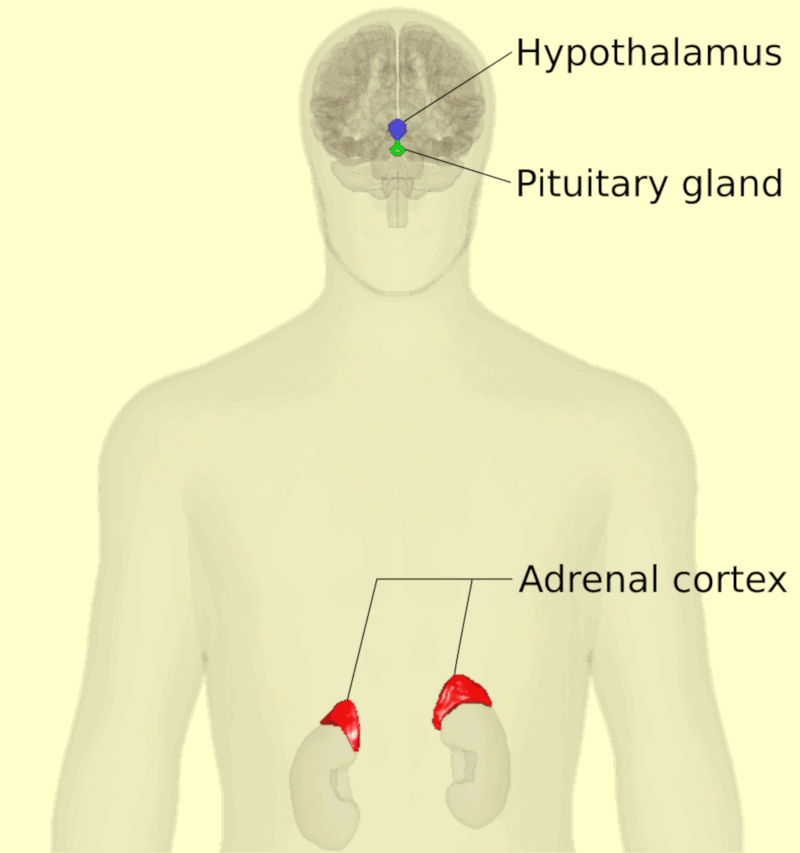

Three interacting hormonal glands play a particularly important role in fetal development: the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland (both situated in the brain), as well as the adrenal glands (situated on top of the kidneys). Together they form the so-called hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

One function of the HPA axis, among many others, is the production of glucocorticoid hormones. Glucocorticoids, generally, have a positive effect on behavior, cognition, and mood, and they are necessary for normal brain development. However, an excess of these hormones, induced by chronic stress during pregnancy, can damage the brain of the fetus. It can, furthermore, lead to a severely decreased production of glucocorticoids (“negative feedback regulation”), which in turn leads to neurodevelopmental disorders of the fetus.

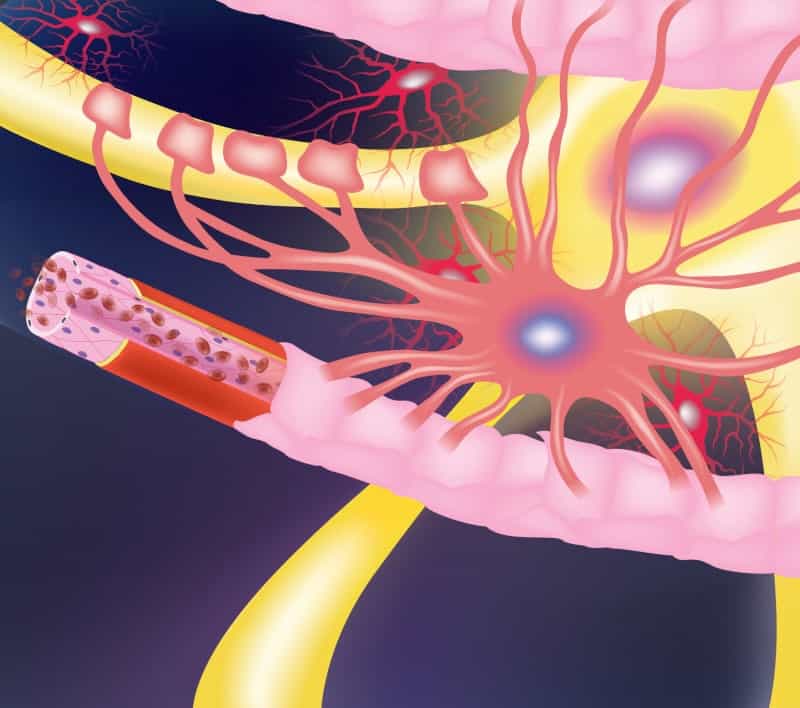

Moreover, this decrease in glucocorticoids may reduce the number of astrocytes, which are specialized, star-shaped cells situated in the brain and the spine. Astrocytes play an important role in the support and nourishment of nerve cells. Glucocorticoids can also damage microvascular endothelial cells – the cells lining the smallest vessels of our circulatory system.

In summary, while glucocorticoids are essential for fetal development, too much of them can hurt the whole neurovascular unit (NVU), which includes brain cells as well as the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier.

In light of the dangers for newborns, the authors see a need for deeper research into the mechanisms of glucocorticoids in fetal development: “If [these mechanisms] were understood better, brain injuries of infants with IUGR could be reduced.”

Read the original article here: