Early Career Researchers Stand to Lose the Most from Covid-19

COVID-19 impacts everyone in academia – faculty, administrators, students – but it could impact junior faculty members and their careers the most.

This essay is part of the series “The New Normal: Perspectives on the Impact of Covid-19 on Academia”.

Since the start of the pandemic I’ve witnessed a huge increase in researchers in my field following and using Twitter. People used it a lot before but now, they’re using it widely to promote their work, comment on each other’s work, and find informal collaborators. It’s no coincidence that the vast majority of these researchers tweeting online are at an early stage of their careers – assistant professors, postdoctoral fellows, or doctoral students. Why? – because their usual routes to connect such as academic conferences and workshops simply aren’t there anymore or they’re organized online with much less one-on-one or small group interaction.

Traditional Channels Disappear

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with researchers using social media platforms if they find value from doing so but to me, this indicates a wider, perhaps concerning trend. Could it be that junior researchers are turning to Twitter and other social platforms because traditional academic channels have all but disappeared due to the pandemic? Whilst experienced academics already have the networks to keep connected – it’s those at an early stage of their careers who might bear the brunt of the virus.

“Conferences, workshops, and research seminars are about so much more than presenting work.”

One area that’s rapidly contracting is conferencing. For well-connected, senior academics, conferences, workshops, and research seminars are a great way to meet up with long-standing colleagues and exchange ideas. However, for researchers at an early stage in their careers, they’re critical for scholarly progress and consequently for success, recognition, and promotion. These events are about so much more than presenting work. There is huge value derived from the interactions that happen outside of the formal programme – the quick chats over coffee, the introductions made over drinks, the in-depth conversations had at dinner. Often, this is where the real work happens and even more importantly, where new collaborations start.

Finding New Voices

Whilst senior academics might take these informal encounters for granted, junior academics depend on them. Face-to-face conferences, workshops and research seminars, and the social interactions associated with these events are where early career researchers and PhD students get noticed by established scholars. They are where new researchers can promote their work, discover funding opportunities, find collaborators, and build their networks. They’re also often how senior academics find new voices or discover new perspectives – this is important too. In social sciences, as in most other areas, emerging scholars are key to moving the frontiers as they are the ones who will adopt new techniques, new data and new approaches.

We must remember that conferences are crucial for any early stage academic and without them, they’re less likely to be heard, promoted, and progressed. Although individual careers suffer, it is scholarship that suffers more broadly, as well as the circulation of knowledge, and the diversity of ideas. This is something that academics, universities, publishers, and indeed society as a whole should be concerned about.

Intensive Learning

“Lack of face-to-face contact will impact how early stage scholars learn.”

As an economist, the use of digital channels for communication and collaboration is common and widespread, however these channels can’t – at the moment – replicate the intensive learning that in-person group interaction provides. This is of a particular concern to me as lack of face-to-face contact will impact how early stage scholars learn.

For example, in my field it is very common to hold small on-campus research seminars where an external speaker joins us in the department for a few days. We invite them to share their research with us in detail. We have group discussions where we exchange ideas and feedback on each other’s work. That intensive interaction and one-to-one exchange cannot currently be recreated online as it requires someone being present and fully available.

Providing opportunities for relationship building and intensive learning is critical for a junior researcher. It helps them hear about the most up-to-date, still unpublished research, receive feedback on their own work, build connections, and learn academic citizenship.

Workloads Increase

Finally, teaching is another area that may have a disproportionate impact on early career academics as they tend to take on more of it. Younger academics can be more adept at delivering online programmes – they’re better equipped to both design online-friendly course content and more willing to adapt to new teaching methodologies.

However, online teaching takes longer – up to double the amount of time it used to – or at least that what we’ve found over the first couple of terms. There are new systems to become familiar with and new processes to learn and student interaction takes longer.

This will take a toll on researchers already affected by reduced academic interaction possibilities. This does not only affect their fundamental research progress, the ultimate criterion for promotion, and tenure decisions, but may lead to a burn-out they might experience from their work.

In Summary

The pandemic makes for very uncertain times. At the moment, we don’t know how universities will fair, whether overseas students will remain a significant market, and how careers and faculty jobs will be impacted long term. However, it’s clear from what I see that researchers at an early stage need support to promote their work and vital connections – because without new voices, academia as a whole will suffer.

We recommend this related collection of think pieces

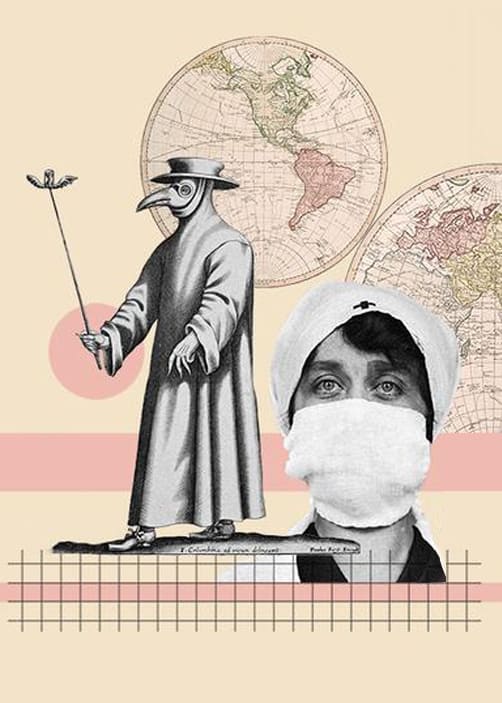

[Title Image via Getty Images]