Class Did Matter in the Election, But Not in the Way We Expected

The problem in understanding Donald Trump's election may be our simplistic expectations rather than how the working class actually voted.

Median family incomes in America have grown very little in recent decades and income inequality is growing as the rich get richer. Many middle and lower income families have very modest wealth levels. Guaranteed pensions are fading and most families have modest savings for retirement. Economic stress is reported to be high, even after years of steady job growth. It would seem that class divisions driven by economic situations would have dominated the 2016 elections.

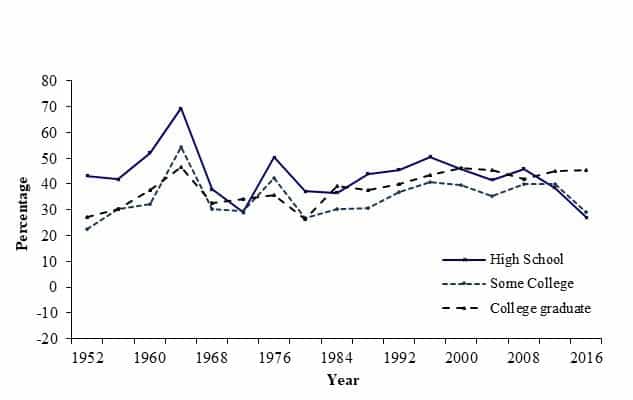

Polls and commentary suggests that this occurred, but not in the ways many expected. In 2016 the voting inclinations of the white working class became a central focus as polls found they were voting Republican. Many claimed that Donald Trump won the presidency by attracting the white working class. Those without a college degree and those with a high school degree or less voted Republican.

The surprising matter was that Republicans were winning the votes of the working class, a reversal of what many expected. Aren’t Democrats the party of the working class?

“The problem in understanding 2016 may be our simplistic expectations and not how the working class voted.”

The reasons for this reversal are clear to many. Class as an economic factor has declined and been displaced by class in cultural terms. Class is defined by many in terms of education. Those with less education are seen as culturally conservative and less tolerant and accepting of others. As a result they are more likely to have opinions seen as high on racial resentment, rural resentment, authoritarianism, or cultural resentment of how liberal elites characterize them. And they are less likely to accept immigrants.

Trump appealed to the intolerant and attracted their support. The conclusion is that Republicans now represent the working class and Democrats the well-educated, a reversal of prior patterns, with cultural politics driving the change.

If all this is true, class as an economic matter has become decidedly secondary in American politics. But despite the prominence of this commentary, there are reasons to be cautious about accepting all this.

The history of class voting is not what many presume. It is not so clear that some great reversal has developed. It is also possible that Trump’s appeal and his electoral base are not that different from that of prior Republican presidential candidates. It is also possible that the voting patterns reflect a class reaction, but in ways not expected. The problem in understanding 2016 may be our simplistic expectations and not how the working class voted.

Checking in with The History Of White Voting

Much of the amazement about 2016 revolves around the finding that working class whites voted for Trump. The reaction is driven by wonder that a wealthy builder who has never treated labor well would attract their votes. But the history of white voting suggests that there was not something remarkably different about 2016.

“The Democratic Party has been more sympathetic to non-whites, and whites have reacted to that by voting Republican for decades.”

We have data on voting patterns in presidential elections that go back to 1952. In the last 60 years, of 17 presidential elections, whites at all education levels have voted Democratic only 4 times, and even then, generally only barely. It is nothing new that a Republican candidate won whites or whites with less than a college degree. The Democratic Party has been more sympathetic to non-whites, and whites have reacted to that by voting Republican for decades. If all voters (non-whites) are included the percentages for all education groups jump 5-15 points, depending on the election.

The 2012-2016 Puzzle

Even with this caution about how much the present differs from the past, the results for 2012 and 2016 are different. A reversal did occur. Why is the interesting question. The conventional answer is that Trump combined traditional Republicans with the intolerant to win enough states to win the Electoral College.

The simplest problem with that explanation is that these same intolerant voters went for Obama in 2008. They then defected.

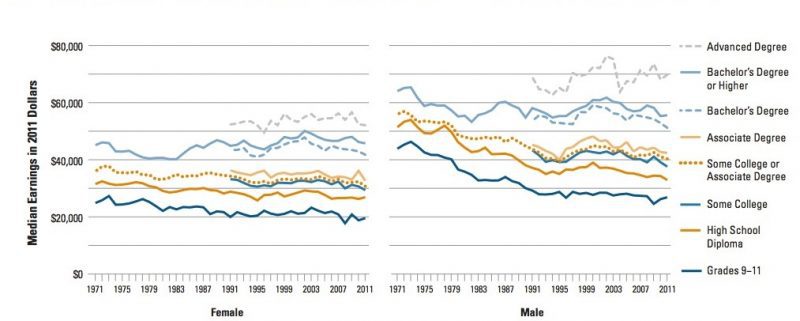

Why they did may lie with the economy and the relevance of class in voting. In the last several decades median family incomes have stagnated, even as more wives have entered the labor force and experienced some gains in wages. The returns to education have increased. Those with higher education have experienced modest gains while those with less education have experienced gradual and steady declines.

Figure 2 indicates how much education has come to affect wages. It compares those 25-34 in any given year by education levels. Those with less education are not faring well. They have suffered significant declines in earnings, which in turn affects home ownership, retirement savings, and prospects for their children.

The Republican / Trump Narrative

Voters look for an explanation of what is happening to their lives. Why are my wages not growing? Republicans are providing an answer that seems simple, intuitive and plausible. Government has imposed so many regulations on business and so many taxes that business has less money to invest in new ventures that create jobs. If regulations are removed and business taxes are lightened, business and jobs will flourish.

“Why are my wages not growing? Republicans are providing an answer that seems simple, intuitive and plausible.”

Democrats argue that all this will just make business wealthier and that the problem is inadequate incomes to provide markets for more goods. We need a balanced economy, with government encouraging business but restraining its excesses and tendencies toward irresponsibility. That argument does not seem to sell as well.

Despite all the talk about how different Trump is, he essentially embraced this argument. He differs somewhat in that he added culprits to the story. The conventional Republican argument is that government hinders and just needs to get out of the way. Trump added bad guys who were consciously harming the economy and workers. Global elites and “stupid and corrupt” elites (globalists, bureaucrats and politicians) were conspiring to engage in free trade that was harming American workers.

They were enacting bad trade deals that allowed business to ship jobs that had paid well to foreign countries. They agreed to allow mass illegal immigration of those who would work for low wages and take the jobs of Americans. They were rigging the system to make themselves rich and selling out American workers.

He was presenting voters with a simple causal argument that explained to some workers why their fortunes were declining. He, an independent businessman, self-financing his campaign, would be their voice. Many saw this as demagoguery, but others saw it as an explanation of what was happening.

Responding to Events and Arguments

The central question is why would the working class believe him and what does all this have to do with class? A group that has not done well, and has never been strongly inclined to vote Democratic, took a chance. The economic recovery that began in 2009 has not reached many voters. Their wages are still stagnant and they are experiencing many problems. Many voted for Obama but moved to Trump because perhaps he could do something that might affect their lives. It was a gamble they were willing to take in hopes of improvement.

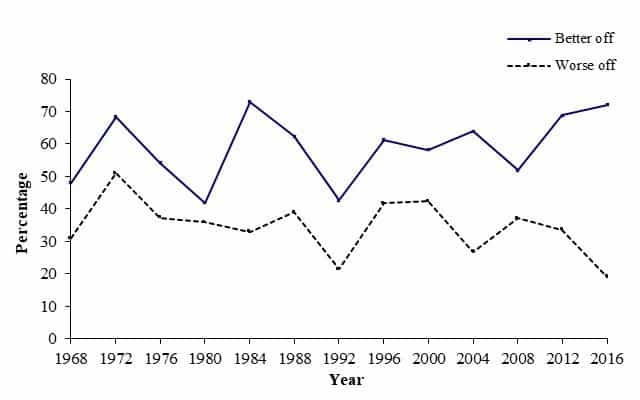

In many ways Trump’s election follows a traditional pattern. Voters think back on the previous years and assess how well things have gone for them. If things have gone well, voting for the party of the current administration is a reasonable choice. Those who have not done well may well see little reason to continue with the current party. Figure 3 shows how people with different recent economic experiences have voted in presidential elections.

Those who have done well vote for the party holding office before the election. Those who have not done well vote against the exiting party. If 2016 was unusual it was that those who have not done well moved strongly against the Democratic candidate. Their level of support for the exiting administration is the lowest recorded in the data we have since 1952.

That takes us back to the role of class and our expectations. Most analyses of class assume that we should measure the impact of class by how much the lower / working class votes Democratic. That presumes their self-interest must be voting Democratic.

The 2016 election is an example of a class making a different assessment.

A Democratic president had been in office for 8 years. Their economic fortunes were worse. Those without a college degree were steadily sliding economically. The Democratic candidate took large fees from Wall Street for speeches. Taking a chance on Trump, with all his personal character issues, would still seem to be a better choice than continuing with Democrats.

As Trump said in trying to attract black voters, “What have you got to lose?” – that could also be seen as how many working class voters saw Trump. Class mattered, but not as expected.

The Intolerance Issue

So what do we make of all the claims that Trump attracted the intolerant? If we take the survey results presented as valid, the answer is that those attitudes did matter. Those who say blacks should work harder voted supported Trump at high levels, as did those who said authority should obeyed, and as did those who say immigrants pose a threat to America. Those results are clear and convincing.

“There are reasons for being cautious about the emphasis that has been given to the aggrieved, intolerant, or resentful.”

But there are reasons for being cautious about the emphasis that has been given to the aggrieved, intolerant, or resentful. Analyses using various resentment / intolerant scales are cross-sectional within 2016. Clearly those higher on these scales voted strongly for Trump. But there have always been the intolerant in American society. Concluding that this explains Trump, with all his deficiencies, neglects several issues. Was the overall level of resentment higher than in prior years?

If it was not, then it is questionable whether something different happened in 2016 involving the role of intolerance. Did Trump receive a higher level of support among the resentful than in prior years? That has not been documented. If not, is anything different from prior Republican electoral support?

There are also the costs of his stances. Even if he did accentuate his appeal among the resentful, there is the issue of whether his positions also alienated those less resentful such that his net support was no greater. These questions are not addressed by 2016 cross-sectional analyses and need to be before accepting interpretations that resentment played a particularly powerful and unique role in 2016.

Equally important is the issue of what such indicators as racial resentment and authoritarianism are capturing. The obvious presumption is that these indicators capture the attitudes of voters about race and authoritarianism. If you don’t think blacks work hard enough, you are resentful of blacks, and perhaps racist. If you are authoritarian you adhere to a rigid set of rules in life and may well be sympathetic to strong authoritarian leaders such as Trump. In short, voters scoring high on these indexes may have opinions or personalities not conducive to tolerance in American society and they find Trump attractive. These voters are troubling while those holding opposite opinions are not.

Another interpretation is possible. There are, to be sure Americans who are racists. That is, they believe non-whites are inherently inferior. There are those intolerant toward immigrants, diverse values, and homosexuals. But the issue is whether all these indexes are about these positions.

Bill Clinton once said “The American Dream is that if you work hard and play by the rules you can go as far as your God-given talent can take you.” What if voters think that playing by rules is not working or that some groups are getting an advantage? Long-term slides in economic fortunes create frustration and a sense that the game is not working for you. What these indexes capture is not entirely clear.

Resentment and the Working Class

The “cultural” interpretations all focus on opinions held by the working class. The presumption is that their opinions are inappropriate for a democracy. It is also possible that the white working class resents how elites characterize them. They see snobbery in how they are portrayed.

As a sympathizer put it: “Whether they are the academic, media, and entertainment elites of the Left or the political and business elites of the Right, America’s self-appointed best and brightest uniformly view the passions unleashed by Trump as the modern-day equivalent of a medieval peasants’ revolt. And, like their medieval forebears, they mean to crush it.”

Being dismissed as racist creates anger that Trump has articulated.

Why voters supported Donald Trump will fascinate us for some time. The most important matter for politicians in a democracy is to try to understand what motivates voters. That is not an easy task. It takes talking with voters and hearing how they see the world and what arguments they accept and why.

Understanding Trump voters means not labeling them but considering different possibilities of what matters to them.

[Title Image by roya ann miller via unsplash.com]