Coming Home and Coming Out? Germany, EURO 2020, and the Battle for Queer Rights

Donning a rainbow flag in the face of international anti-queer measures is not enough. To be taken seriously as an LGBTQIA+ rights advocate, Germany needs to reckon with its own complex and difficult past first.

With the 2020 European Football Championship having come to its dramatic close (albeit delayed by a year), it is a suitable time to reflect on the fact that the tournament demonstrated many of the usual and predictable tensions of any major international sporting event. Not only did it not come home, despite the Herculean efforts of the England team, but that very statement and others became emblematic of a deep hypocrisy in our understanding of where sport lies in society. Entreaties to ‘keep politics out of football’ were made by those who seem not to recognise that politics has always been part of football—indeed, a war was fought over a football match—and that sport has often been an important driver of political and social change.

One of the most notable instances during EURO 2020 was the coinciding of the tournament with both Pride Month and also the passing of a far-reaching anti-LGBTQIA+ law in Hungary. This law, proposed by the ruling authoritarian Fidesz Party and with the support of the far-right Jobbik Party, makes it illegal to share information about sexuality and gender identity that could be considered ‘promoting’ queerness to under-18s. Echoing generations of moral panics before this one, the government argues that such material ‘could […] confuse [children’s] developing moral values or their image of themselves or the world.’ It is no surprise that parallels have been drawn to Russia’s ‘gay propaganda’ laws, or to Britain’s infamous Thatcher-era Section 28.

The response to this, at a tournament level, was immediately noticeable. Germany captain and goalkeeper Manuel Neuer wore a rainbow-coloured captain’s armband in Germany’s first and second group stage matches against France and Portugal, leading to a UEFA investigation that ultimately determined he wore it for a ‘good cause.’ Emboldened, the mayor of Munich, Dieter Reiter, announced that he would request that the Allianz Arena be lit in rainbow colours when it hosted the third-round match against Hungary. UEFA’s response was chaotic, insisting that this (but not the armband) was a ‘political’ move that could not be allowed, while changing its own branding to reflect Pride.

“Throughout Germany, politicians and media alike rose in defence of what apparently had become shared values.”

Throughout Germany, politicians and media alike rose in defence of what apparently had become shared values. Editorials castigated UEFA for its cowardice. As fans flocked to the stadium with rainbow flags of their own, the acting editor-in-chief of Europe’s largest newspaper, Paul Ronzheimer of BILD-Zeitung, proudly displayed the front cover of the next edition, with the German black-red-gold flag seamlessly merging into the rainbow Pride flag. The message was clear: Germany is a defender of LGBTQIA+ rights. But if this is the case, then it is a very late development. Ronzheimer’s front cover was evocative but glossed over BILD’s own homophobic and queerphobic legacy, which has customarily sensationalised scandal over substance. (Perhaps most infamously, during a murder trial in 1974, BILD ran an entire series of stories entitled ‘Crimes of Lesbian Women’, in which the newspaper portrayed lesbians as violent, murderous, and inherently devious.)

German politicians, including Chancellor Angela Merkel, lined up to condemn Hungarian president Viktor Orbán, but many of them—including, quite famously, Dr. Merkel herself, as well as 224 out of 309 of her CDU colleagues—had opposed marriage equality legislation up to the point that it passed through the Bundestag in 2017. Merkel’s party colleague and one-time potential candidate to succeed her as chancellor, Friedrich Merz, may not have spoken out publicly about the Hungarian laws, but he and other conservatives have recently drawn attention to themselves by criticising ‘gender-inclusive language’ as an example of ‘Gendergaga’ or ‘Gender-Wahnsinn’ (‘Gender-Madness’). Previously, Merz had joked that he was fine with homosexuality ‘as long as [longtime openly gay Berlin mayor Klaus Wowereit] doesn’t come on to me’, and in 2017 he drew criticism for implicitly approximating homosexuality and paedophilia.

From Persecution to Absolution?

Indeed, Germany’s entrance on the stage of LGBTQIA+ advocacy was belated, patchy at best and, in many cases, the wait continues. Immediately after the Second World War and the era of National Socialism, the extant ‘sodomy law’ that prohibited male-male sex—§175 Strafgesetzbuch—was neither abolished nor reformed to any major degree. Indeed, for many victims persecuted by the Nazis for their sexuality, their liberation from concentration camps was short-lived, as they were then returned to police custody. In the first twenty years of the Bundesrepublik, approximately 50,000 gay men were prosecuted under §175, this number being roughly equivalent to the number prosecuted under the NSDAP between 1933 and 1945. Reforms in 1969, and again in 1973, largely removed the teeth of the legislation. Nevertheless, for all intents and purposes, the infamous ‘sodomy law’ remained on the books, even if it was not enforced.

In East Germany, §175 was also adopted but ceased to be implemented as a tool of the criminal judiciary by 1957. The distinctions between the two Germanies meant that, throughout the Cold War, queerness in West Germany continued to be stigmatised and criminalised for much longer, while in the East queer relationships and behaviours were tolerated by the state but remained largely hidden as they were still considered biological ‘problems’ or vestiges of bourgeois ‘decadence.’ By 1989, East Germany’s unequal age of consent law (§151) was struck down, meaning that homosexual acts could be consented to at the same age as heterosexual acts (14). When Germany reunified after the fall of the Berlin Wall in November of the same year, though, the West German Criminal Code was reimposed, thus reinstating §175 in word if not in deed, and once again stipulating a higher age of consent for queer sex than for straight sex. §175 was only finally removed without replacement in 1994.

The long arm of the law also had consequences for Germany’s much-vaunted Erinnerungskultur (Remembrance Culture), which is often seen as a guiding example of a country coming to terms with its difficult past. Since §175 not only predated the Nazis, but also continued well after their downfall, in the eyes of the state those who had suffered under its provisions were criminal or had engaged in criminal behaviour. For this reason, it was not until 2017—the same year that marriage equality passed through the Bundestag, and some 23 years after §175 was abolished—that those who had been persecuted for their sexuality by the Nazis were offered compensation. Prior to this, any measure of remembrance for queer victims of persecution had been difficult to come by.

In 1985, a pink triangle memorial was commissioned, to be placed at the Dachau concentration camp memorial, but its installation only occurred ten years later after years of bitter recriminations and the suggestion that remembering gay victims would cast aspersions on other persecuted peoples. The unveiling of the Memorial to the Persecuted Homosexuals under National Socialism in Berlin in 2008 was met with similar criticism, especially due to its proximity to the Holocaust Memorial. Only as late as this year, the lesbian victims of the concentration camp at Ravensbrück are to be commemorated with their own memorial at the site, after several years of contestation.

“Where advances have been made in Germany’s relationship with LGBTQIA+ rights, it is clear that these are largely focused on white, homonormative, cisgender queer communities.”

Even in the foreground of the Germany-Hungary match, Germany’s hypocrisies are still to be seen. Where advances have been made in Germany’s relationship with LGBTQIA+ rights, it is clear that these are largely focused on white, homonormative, cisgender queer communities. Queer people of colour (POC) in Germany continue to experience significant hardships and discrimination, and Germany’s labyrinthine refugee asylum system makes it difficult for LGBTQIA+ asylum-seekers to access vital services and support.

Further, while the news broadcasters on the German television channel ARD, which televised much of the EURO 2020 tournament, were uncharacteristically strident in condemning both Hungary for its queerphobia and UEFA for its moral cowardice, just three months earlier the ARD’s own acclaimed crime show Tatort drew serious criticism for its use of transphobic stereotypes. On the very day of the match itself, the Bavarian Landtag deputy Tessa Ganserer was forced to openly explain her status as a transgender woman while she attempted to access a COVID-19 test station, by dint of Germany’s ageing and discriminatory ‘Transsexual Law’ (TSG). The TSG was challenged for reform earlier this year in the Bundestag, but this failed due to the opposition of the governing coalition of the CDU and the SPD, including many of the same politicians who lined up to denounce Hungary and declare Germany a bastion of LGBTQIA+ rights.

So: in the face of international anti-queer measures, should Germany simply stay silent? Absolutely not. Indeed, the queer memorial in Berlin includes on its plaque an admonition that Germany, because of its history, has a moral obligation never to allow that history to repeat itself—a worthy goal and an admirable task. But nor can this goal be accomplished by obscuring the past and present to score cheap geopolitical points. The Hungarian laws are discriminatory and inhumane, and Germany’s political, social, and media might should certainly be drafted into the fight against them. But the fact that the Hungarian laws are manifestly bad does not forgive the German TSG of its own discriminatory shortcomings. Condemning Viktor Orbán for his homophobia does not wash away the homophobia of the state as it was and its politicians as they are. And donning a rainbow flag does not provide the media absolution for its decades of hatred.

Reckoning with these issues can only be accomplished by a reckoning with Germany’s own complex and difficult past—and that remains a long time coming.

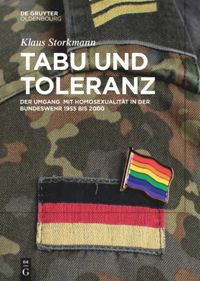

This German-language title might also be of interest to you

[Title Image by Mercedes Mehling via Unsplash]